Village Head Wins Regenerative Farming Award

Leonard Ncube, Victoria Falls Reporter

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Leonard Ncube, Victoria Falls Reporter

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

Photo credit: IGugu Trust

I am writing this on World Water Day, March 22nd. The UN’s tag line for today is ‘Be the change. Every drop counts.’ This is very true. If we are going to return water cycles everywhere to what they used to be, then it will start with each one of us understanding the basics of the water cycle and acting to support a healthy water cycle.

The action we need to take is not that complicated. The complexities lie in the wonderful way in which Nature drives the water cycle, when the basics are in place. We do not fully understand these complexities, but we understand what we need to do.

Nearly everywhere around our African continent, water falls as rain, falling as snow in a few spots here and there. If that rainwater sinks into the ground, it is a productive force. If it runs off the ground it is a potentially destructive force.

We, the women of the world, meeting together in Dehradun, India as the ¨Diverse of Women for Diversity¨, and representing 17 nationalities and multiple cultures, welcome and support the decision of the Mexican government through the presidential decree to phase out the use of GMOs and glyphosate.

We are outraged and dismayed that the Government of the United States is trying to pressure the government of Mexico to impose GMO transgenic Corn in violation of Mexico´s sovereignty and its sovereign rights enshrined in international agreements.

We as diverse women of the world working for protection of Biodiversity and resisting the imposition of GMOs which destroy our biodiversity and our food sovereignty support the Mexican government, condemn the bullying by United States and the biotechnology industry to force GMOs on Mexico and the world violating the Convention of Biological Diversity and the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety which enshrine sovereignty and the precautionary principle. We also ask the European Commission to stand by the decisions they have made under the precautionary principle.

We call on the government to:

We as diverse women were born as movement in the defense of biocultural diversity and resist GMOs everywhere since GMOs, pesticides and the industrial food system are the single biggest reason for the disappearance of biodiversity. We will continue our struggle in defense of life, diversity and freedom.

WESTERN TURKANA, Kenya—Driving across Northern Kenya’s Turkana County, the seemingly boundless terrain of sand dunes, dusty brushes and hard, dry soil makes it hard to imagine anyone could farm and eke a living out here. As Kenya and the Horn of Africa are confronted by the fifth consecutive failed rainy season since September 2020—the region’s worst drought in four decades—around 22 million people (roughly the population of Taiwan or Sri Lanka) are food insecure, says a U.N. World Food Programme report released last month.

In Kenya, the number stands at 4.4 million as of December 2022, with children needing acute treatment for malnutrition on the rise.

The numbers and immense toll on pastoralists and agro-pastoralists, who rely on both crops and livestock, grow starker still: their animals have been dying en masse with, 2.5 million livestock deaths recorded by the Government of Kenya, and entire communities pushed to pursue different livelihoods as traditional means and resources fail.

Meet Gabe Brown. If you haven’t read his groundbreaking book Dirt To Soil, visited his North Dakota farm, seen his Netflix documentary Kiss The Ground, or his Congressional testimony, you can find Gabe speaking around the country about regenerative farming.

Brown describes how regenerative agriculture not only fixes farming, but also the farming business model. It delivers more nutritious food, healthier rural culture, and enables smallholder farmers worldwide to feed themselves and the rest of us. It’s also essential if we want to solve the climate crisis.

“Regen ag,” as it’s called, enables farmers and ranchers to sequester enormous amounts of carbon in the soil — and at a profit. If farmers around the world adopt the practice, it will start to roll climate change backward. Couple that with renewable energy, and it solves the climate crisis.

During COP 27, a group of women from Abya Yala(1) raised their firm and deep voices to speak up about food sovereignty in regions that are so different and yet alike as America and Africa. The talk was organized by Regeneration International and OMANIAP.

At the Green area of the climate summit in the Tutankhamun auditory, the powerful female voices pondered about the impact of climate change in the lives of women and their communities, the consequences for food sovereignty and the importance of ancestral science and knowledge, demanding public policies to guarantee their rights, territories, water, biodiversity, seeds and preserve their traditional foods.

Mercedes López, Vía Organica’s Director in Mexico City started the discussion in the panel speaking about the need for communities to choose the concept of food sovereignty over food security (used by FAO). Food sovereignty is more comprehensive and prioritizes food, ancestral seeds, territories, and water for the people. It is the people who have the option to choose healthy, local and nutritious food and the right to protect themselves from poor quality agricultural imports foreign to their traditional diet. López insisted on the importance of the participation of communities in agricultural policy; prioritizing and acknowledging farmers’ voices.

Food security, on the other hand, implies access to sufficient food regardless of its origin, processing and use of agrochemicals and/or transgenic seeds, all this without respect or consideration to food culture and pertinence.

She called out the fact that Coca-Cola and Nestle where sponsors of COP 27. Companies that have favoured industrial agriculture, warming of the planet and cause of obesity and malnutrition; in addition to polluting the planet with their plastic containers and using water reserves.

Precious Phiri, Regeneration International’s African Coordinator, pointed out that climate change is strongly impacting women from the Global South, and made the point that the term climate change does not seem to her strong enough and it would be better to talk of climate emergency, with economic and social consequences.

She mentioned that it is important to go beyond food security, under which groups of donors are pushing communities to have access to any type of food, just like the green revolution model pushed by Big Ag, without taking care of diversity and specificity of nutrition amongst different communities.

This represents a big challenge for farmer communities that are pressured to adopt a model that places them in insecure situations and the answer ends up being worse than the problem. She concluded her participation commenting that climate emergency is creating a very serious economic, environmental, and social situation and it affects more women, who have the challenge to feed their families.

Wilma Mendoza, President of the National Confederation of Indigenous Women from Bolivia (CNAMIB, by its Spanish Initials) mentioned how indigenous women are fighting to keep their identity, seeds, and territories in the face of GMOs and industrial agriculture.

She explained that in Bolivia food sovereignty and security topics are included within the Development Plan, but monocrops are still supported.

Mendoza mentioned that women are more aware about the need to eat their own foods with no agrochemicals or GMOs , and are the seed keepers. It is women-she went on- , who are more affected by droughts, flooding, frosts, plagues and deforestation.

On her turn, Mayra Macedo, Secretary of the National Organization of Andean and Amazona Indigenous Women of Peru (ONAMIAP) mentioned that public policies and food programs in Peru are insufficient and promote monocrops such as oil palm and papaya, invading their Amazonian lands, destroying the rainforest and polluting it.

Macedo said that there are two social central food programs: school breakfast which is deficient because it includes high processed foods and beverages, that only benefit the economy of companies that sell these products and not the communities and promoting raising backyard animals such as guinea pigs which cannot survive in the Amazonian region because they live in cold climates like the Andes. She criticized the lack of vision and knowledge in both programs.

She went on making a call for women to become involved in policy making, specifically in social programs designed to bring back food sovereignty.

The last speaker was Melania Canales Poma, Leader of the Quechua People and Coordinator of the Continental Network of Indigenous Women from America (ECMIA-South Region) who said that indigenous women demand guarantees and respect to their collective territories. She mentioned as an example that in Peru, 49% of the territory is in the hands of farmer and native communities, but the land is being invaded and they are being dispossessed in various legal ways.

She went on wondering how food sovereignty would be possible if women are being deprived of their land and pointed out the importance of reviewing the legal status of the territories. It is indigeneous woman, after all, who have raised their voices against GMOs and defended ancestral knowledges.It is indigeneous women who have demanded rights, opposed machismo, extractivism and dispossession.

The talk ended with comments and questions from the audience, summing up the importance of preserving indigenous practices, knowledge and science from the ancestors; to resist transculturation of nutrition and colonialist customs acquired through migration; demanding recognition and visibility of women’s inputs with fair payments; organization in biocultural spaces; as well as preserving ancestral traditions such as rainwater capture to face the scarcity that is prevailing around the world.

Even though it was a small space in the middle of a vast array of side events, conferences and high level debates, this group of women showed that they are organizing, fighting and proposing new alternatives every day to defend biodiversity, seeds, territory and women’s dignity in different communities all over the world.

1 Abya Yala in Kuna language (Colombia and Panama) means earth, life, territory, flourishing land. “Abia” means “hole of blood”, “mature mother”, “mature virgin”, “land in its full ripeness”. The term is used to name the territory between the American Continent.

When Andrew Dokhole, a community leader in Isiolo, northern Kenya, took on the task of explaining a proposed soil carbon removal project a decade ago, he had to convince largely illiterate people about the benefits of a “foreign” concept.

“Our people didn’t know what carbon was,” says Dokhole. “There is no word for carbon in our local language, not even in Swahili, the national language. Yet the success of the project depended on the pastoralists understanding how the concept works and how it would affect their daily activities.”

Dokhole had done his research. He understood all the nuances of carbon sequestration – the capturing, removal and storage of greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) – so he settled on some vivid illustrations to reach people.

The 27th United Nations climate conference (COP27) ended on Sunday morning with researchers largely frustrated at the lack of any ambition to phase out fossil fuels.

However, there was one silver lining: delegates from low and middle income countries (LMICs) came away with an agreement on a new ‘loss and damage’ fund to help them cover the costs of climate-change impacts.

The final 10-page summary text, which was agreed on 20 November, says that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels requires “rapid, deep and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions” by 2030.

But calls to phase out fossil fuels were blocked by oil-producing states, and some delegates struggled to find reasons to be cheerful at the glacial pace of decarbonization. Many blamed the energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine for a lack of progress on fossil fuels.

Read in Spanish here.

Agave, from the Greek word αγαυή, meaning “noble” or “admirable,” is a common perennial desert succulent, with thick fleshy leaves and sharp thorns. Agave plants evolved originally in Mexico, but are also found today in the hot, arid, and semi-arid drylands of Central America, the Southwestern U.S., South America, Africa, Oceana, and Asia. Agaves are best known for producing textiles (henequen and sisal) from its fibrous leaves, syrup sweeteners, inulin (a food additive), and alcoholic beverages, tequila, pulque, and mescal, from its sizeable stem or piña, pet food supplements and building materials from its fiber, and bio-ethanol from the bagasse or leftover pulp after the piña is distilled.

Agave’s several hundred different varieties are found growing on approximately 20% of the earth’s surface, often growing in the same desertified, degraded cropland or rangeland areas as nitrogen-fixing, deep-rooted trees or shrubs such as mesquite, acacia, or leucaena. Agaves can tolerate intense heat and will readily grow in drylands or semi-desert landscapes where there is a minimum annual rainfall of approximately 10 inches or 250 mm, and can survive temperatures of 14 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 10 degrees Celsius).

The several billion small farmers and rural families living in the world’s drylands are often among the most impoverished communities in the world, with increasing numbers being forced to migrate to cities or across borders in search of employment. Decades of corrupt government policies, deforestation, overgrazing, soil erosion, destructive use of agricultural chemicals, and heavy tillage or plowing have severely degenerated the soils, fertility, water retention, and biodiversity of most arid and semi-arid lands. With climate change, limited and unpredictable rainfall, and increasingly degraded soil in these drylands, it has become very difficult to raise traditional food crops (such as corn, beans, and squash in Mexico) or generate sufficient forage and nutrition for animals. Many dryland areas are in danger of degenerating even further into literal desert, unable to sustain any crops or livestock whatsoever. Besides struggling with corrupt or inept officials, degraded landscapes, poverty, and crop failure, and social conflict, drug trafficking, and organized crime often plague these areas, forcing millions to migrate to urban areas or across borders to seek safety and employment.

Agaves

Agaves basically require no irrigation, efficiently storing seasonal rainfall and moisture from the air it in their thick thorny leaves (pencas) and stem or heart (piña) utilizing their Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) photosynthetic pathway, which enables the plant to grow and produce significant amounts of biomass, even under conditions of severely restricted water availability and prolonged droughts. Agaves reproduce by putting out shoots or hijuelos alongside the mother plant, (approximately 3-4 per year) or through seeds, if the plant is allowed to flower at the end of its 8-13 year (or more) lifespan.

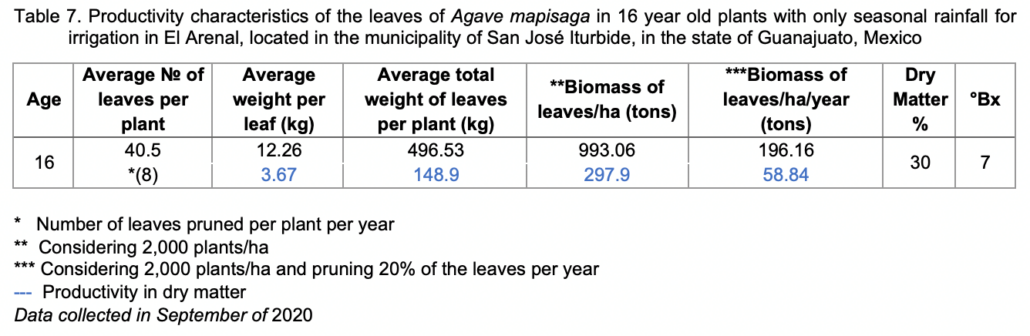

A number of agave varieties appropriate for drylands agroforestry (salmiana, americana, mapisaga, crassipina) readily grow into large plants, reaching a weight of up to 650 kilograms (1400 pounds) in the space of 8-13 years.

Agaves are among the world’s top 15 plants or trees in terms of drawing down large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and producing plant biomass. [Footnote: Park S. Nobel, Desert Wisdom/Agaves and Cacti, p.132] Certain varieties of agave are capable of producing up to 43 tons of dry weight biomass per hectare (17 tons of biomass per acre) or more per year on a continuous basis. In addition, the water use of agaves (and other desert-adapted CAM plants) is typically 4-12 times more efficient than other plants and trees, with average water demand approximately 6 times lower.

Agave-Based Agroforestry

Agave’s nitrogen-fixing, deep-rooted companion trees or shrubs such as mesquite and acacias have adapted to survive in these same dryland environments as well. From an environmental, soil health, and carbon-sequestering perspective, agaves should be cultivated and inter-planted, not as a monoculture, as is commonly done with agave azul (the blue agave species) on tequila plantations in Mexico (often 3,000-4,000 plants per hectare/1215-1600 plants per acre), but as a polyculture. In this polyculture agroforestry system, several varieties of agave are interspersed with native nitrogen-fixing trees or shrubs (such as mesquite or acacias), native vegetation, pasture grass, and cover crops, which fix the nitrogen and nutrients into the soil which the agave needs to draw upon in order to grow and produce significant amounts of biomass/animal forage. If grown as a polyculture, agaves and their companion trees and shrubs can be cultivated on a continuous basis, producing large amounts of biomass for silage and sequestering significant amounts of carbon above ground and below ground (approximately 130 tons of CO2 per hectare on a continuous basis after 10 years), without depleting soil fertility or biodiversity.

In addition to these polyculture practices, planned rotational grazing on these agroforestry pastures, once established, not only provides significant forage for livestock, but done properly (neither overgrazing nor under-grazing, keeping livestock away for several years after initial planting), further improves or regenerates the soil, eliminating dead grasses, invasive species, facilitating water infiltration (in part through ground disturbance i.e. hoof prints), concentrating animal manure and urine, and increasing soil organic matter, soil carbon, biodiversity, and fertility.

Although agave is a plant that grows prolifically in some of the harshest climates in the world, in recent times this plant has been largely ignored, if not outright denigrated. Apart from producing alcoholic beverages, agaves are often considered a plant and livestock pest, along with its thorny, nitrogen-fixing, leguminous companion trees or shrubs such as mesquite and acacias.

But now, the development of a new agave-based agroforestry and holistic livestock management system in the semi-arid drylands of Guanajuato, Mexico, utilizing basic ecosystem restorations techniques, permaculture design, and silage production using anaerobic fermentation, is changing the image of agave and their companion trees. This agave-powered agroforestry and livestock management system is demonstrating that native plants, long overlooked, have the potential to regenerate the drylands, inexpensive feed supplements and essential fermented forage for grazing animals, especially during the dry season, and alleviate rural poverty.

Moving beyond conventional monoculture and chemical-intensive farm practices, and combining the traditional indigenous knowledge of native desert plants and natural fermentation, an innovative group of Mexico-based farmers have learned how to reforest and green their drylands, all without the use of irrigation or expensive and toxic agricultural inputs.

Farmers and researchers have created this new agroforestry program by densely planting, pruning, and inter-cropping high-biomass, high-forage producing species of agaves (1000-2000 per hectare, 405-810 per acre) among pre-existing deep-rooted, nitrogen-fixing tree or shrub species (400 per hectare) such as mesquite and acacia, or alongside transplanted tree saplings. For reforestation and biodiversity in the agave/mesquite agroforestry system, the Via Organica research farm in San Miguel has developed acodos or air-layered clones of mesquite trees. These mesquite acodos are essentially mesquite branches from mature trees transformed into saplings planted into the ground, which, after six months to a year of being watered and cared for in the greenhouse, can grow up to two meters tall.

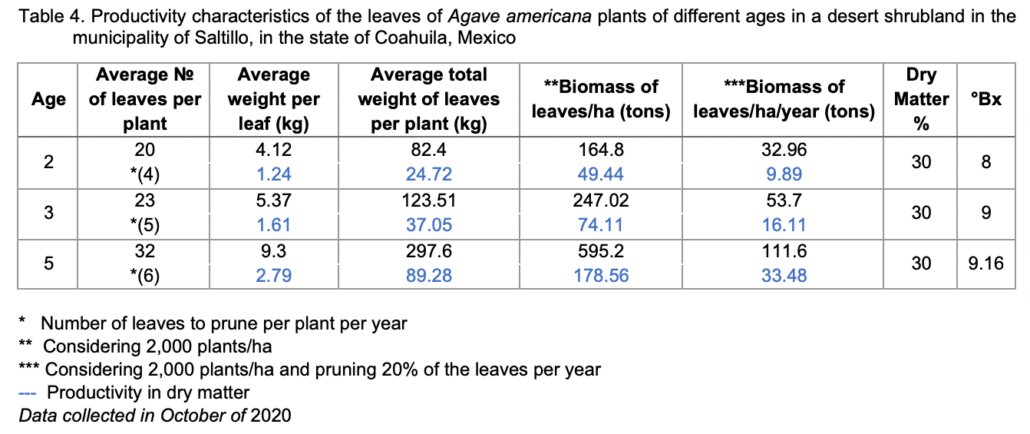

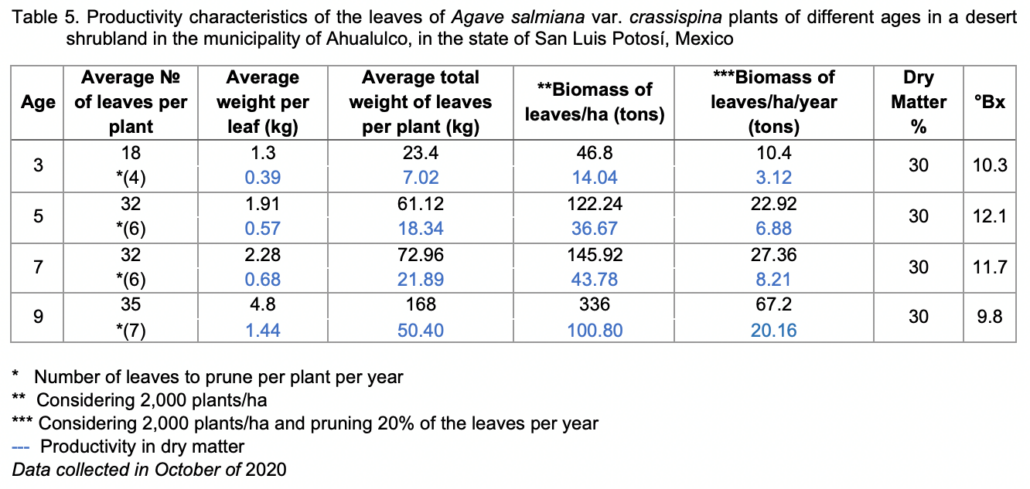

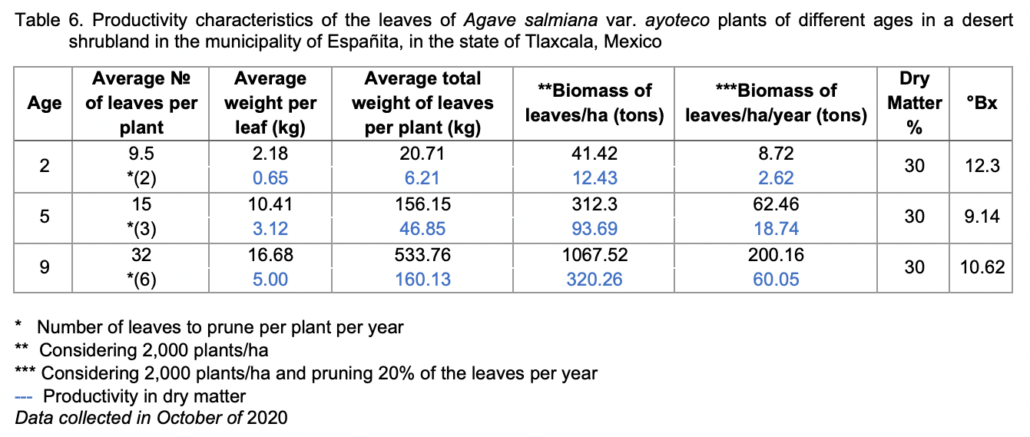

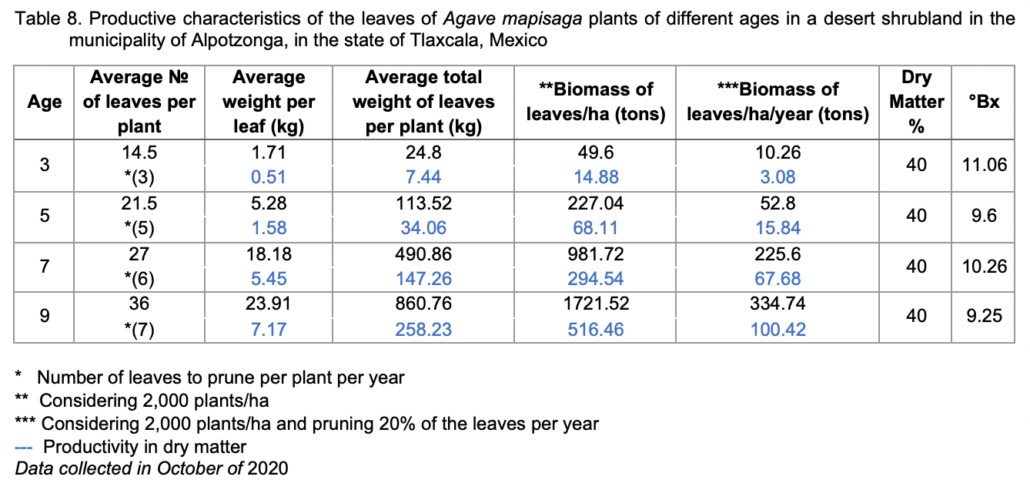

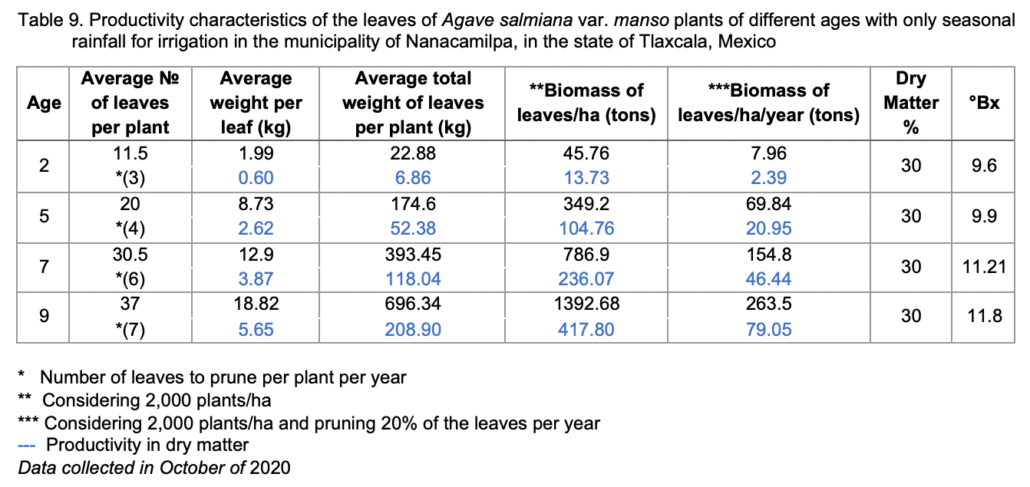

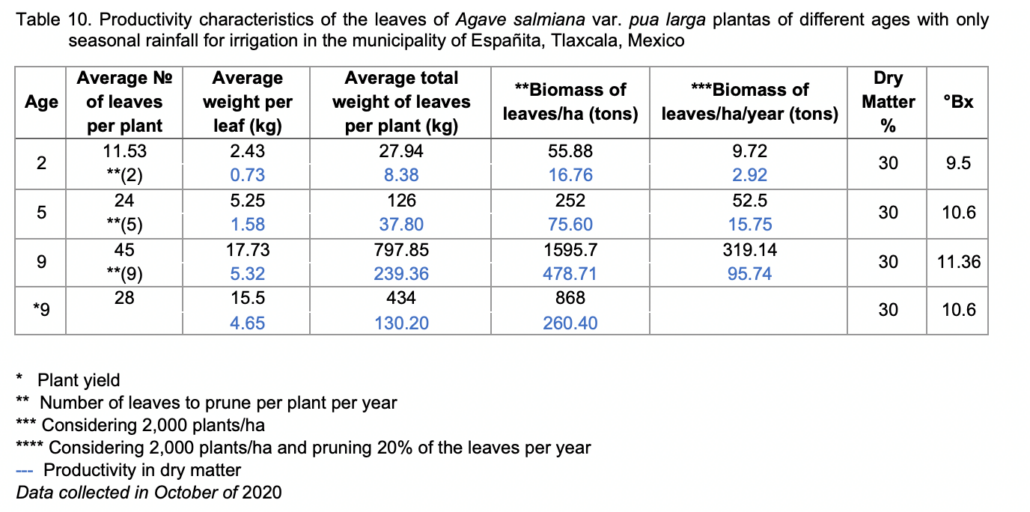

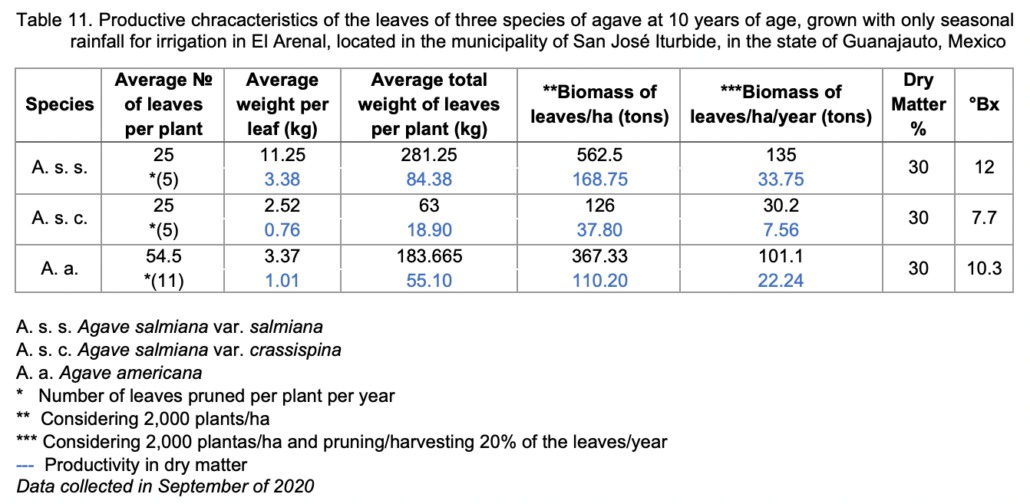

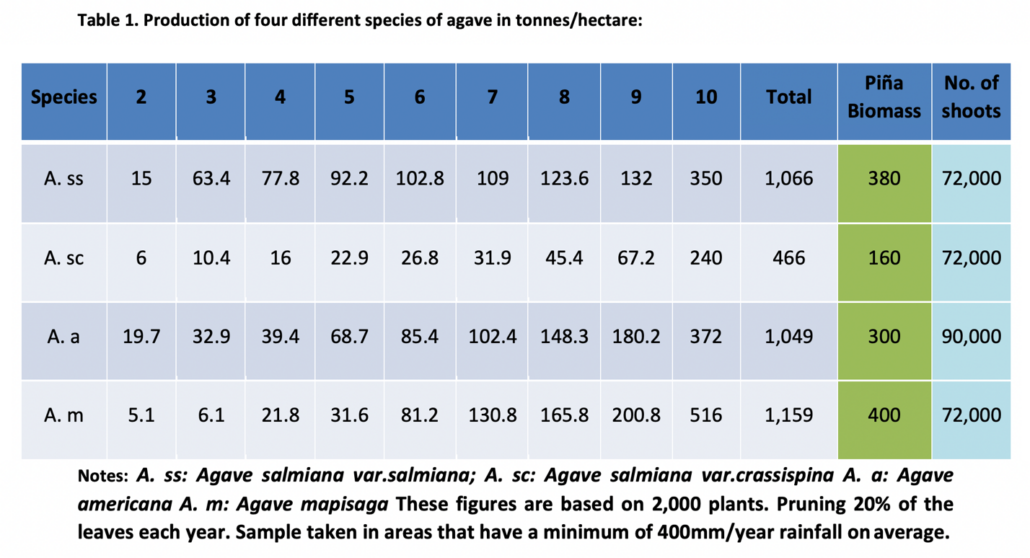

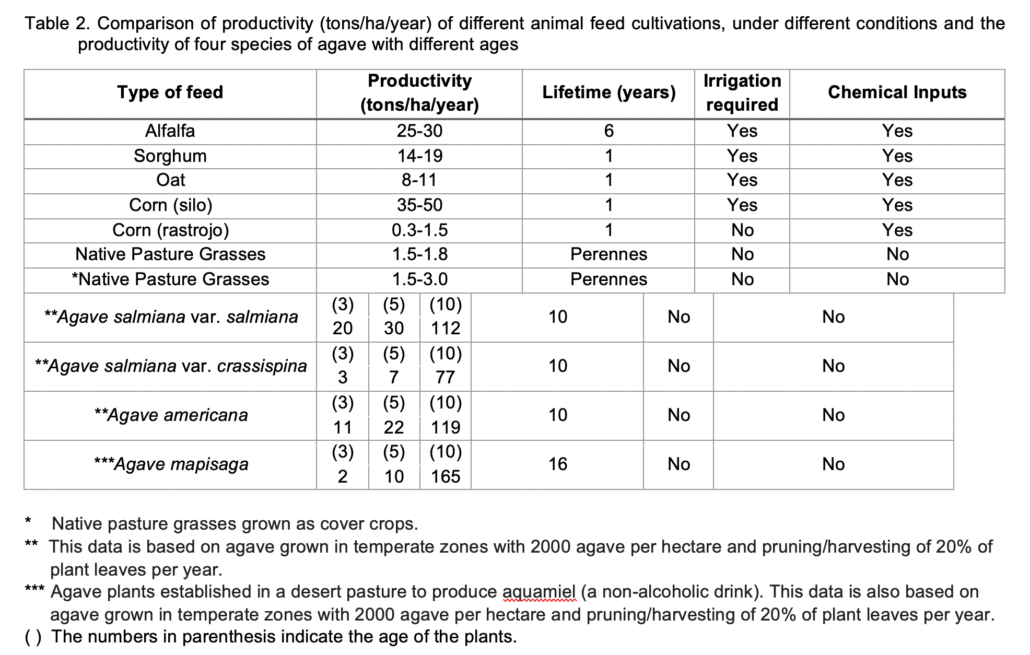

Agaves (especially salmiana, americana, mapisaga, and crassipina) naturally produce large amounts of plant leaf or pencas every year, which can then be chopped up and fermented, turned into silage. Agave’s perennial silage production far exceeds most other forage production (most of which require irrigation and expensive chemical inputs) with three different varieties (salmiana, americana, and mapisaga) in various locations producing approximately 40 tons per acre or 100 tons per hectare, of fermented silage, annually. The variety crassispina, valuable for its high-sugar piña content for mescal, produces slightly less than 50% of the penca biomass than the other three varieties (average 46.6 tons per year).

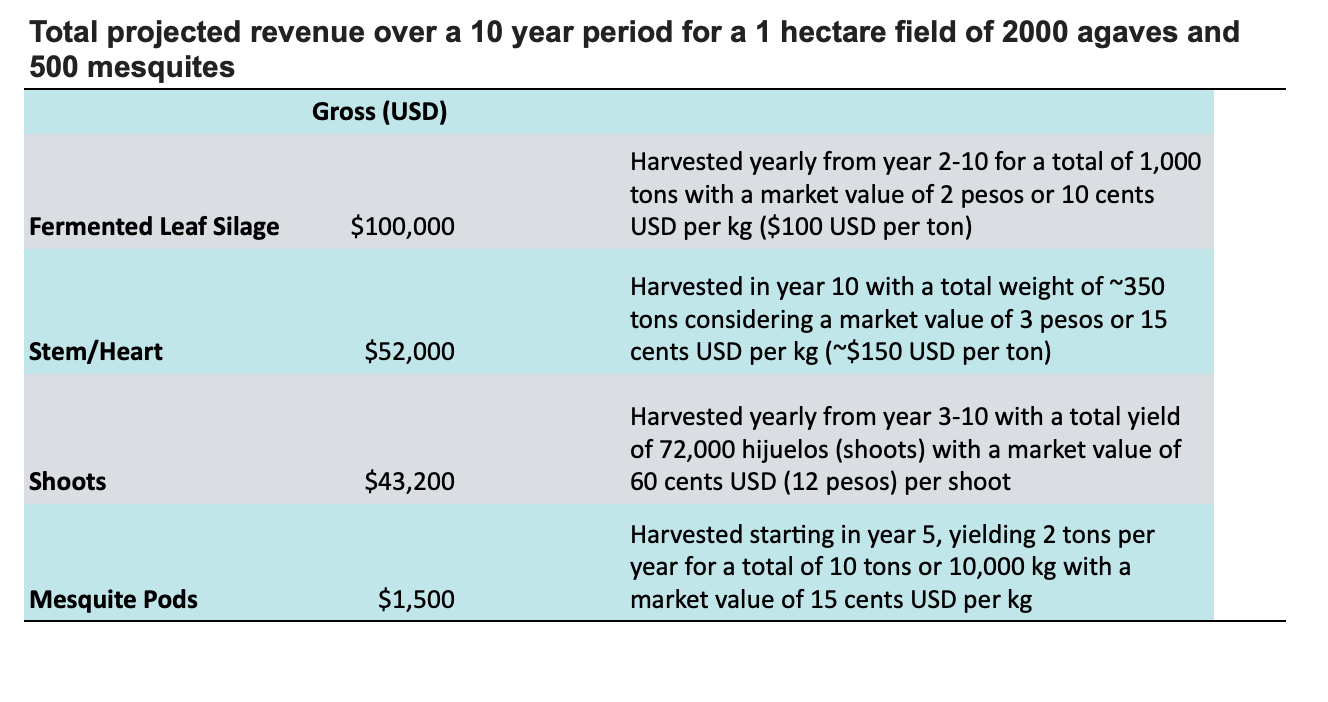

The fermented agave silage of the three most productive varieties has a considerable market value of $100 US per ton (up to $4,000 US per acre or $10,000 per hectare gross income). This system, in combination with rotational grazing, has the capacity to feed up to 40 sheep, lambs or goats per acre/per year or 100 per hectare, producing a potential value added net income of $3,000 US per acre or $7,500 per hectare. Once certified as organic, sheep and lamb production will substantially increase profitability per acre/hectare, especially if organic viscera (heart, liver, kidneys etc.) are processed into freeze-dried nutritional supplements.

In addition, the agave heart or piña, with a market value of $150 US per ton, harvested at the end of the agave plant’s 8-13 year-lifespan for mescal (a valuable distilled liquor) or inulin (a valuable nutritional supplement), or silage, can weigh 300-400 kg. (660-880 pounds), in the three most productive varieties. Again the crassispiña variety has a much smaller piña (160 tons per 2000 plants). The value of the piña from 2000 agave plants for the salmiana, americana, and mapisaga varieties, harvested once, at the end of the plant’s productive lifespan (approximately 10 years) has a market value of $52,500 (over 10 years, with 10% harvested annually) US per hectare, with the market value for inulin being considerably more.

Combining the market value of the penca and piña of the three most productive varieties we arrive at a total gross market value of $152,500 US per hectare and $61,538 per acre, over 10 years. Adding the value of the 72,000 hijuelos or shoots of 2000 agave plants (each producing an average of 36 shoots or clones) with a value of 12 pesos or 60 cents US per shoot we get an additional $43,200 gross income over 10 years. Total estimated gross income per hectare for pencas ($100,000), piñas ($52,500), and hijuelos ($43,200) over 10 years will be $195,700, with expenses to establish and maintain the system projected to be to be $15,000 (including fencing) per hectare over 10 years. As these numbers, even though approximate, indicate, this system has tremendous economic potential.

Pioneered by sheep and goat ranchers, Hacienda Zamarippa, in the municipality of San Luis de la Paz, Mexico and then expanded and modified by organic farmers and researchers in San Miguel de Allende and other locations, “The Billion Agave Project” as the new Movement calls itself, is starting to attract regional and even international attention on the part of farmers, government officials, climate activists, and impact investors. One of the most exciting aspects of this new agroforestry system is its potential to be eventually established or replicated, not only across Mexico, but in a significant percentage of the world’s arid and semi-arid drylands, (including major areas in Central America, Latin America, the Southwestern US, Asia, Oceana, and Africa). Arid and semi-arid drylands constitute, according to the United Nations Convention to Prevent Desertification, 40% of the Earth’s lands.

Alleviating Rural Poverty

Besides improving soils, regenerating ecosystems, and sequestering carbon, the economic impact of this agroforestry system appears to be a long-overdue game-changer in terms of reducing and eliminating rural poverty. Currently 90% of Mexico’s dryland farmers (86% of whom do not have wells or irrigation) are unable to generate any profit whatsoever from farm production, according to government statistics. The average rural household income in Mexico is approximately $5,000-6,000 US per year, derived overwhelmingly from off-farm employment and remittances or money sent home from Mexican immigrants working in the US or Canada. Almost 50% of Mexicans, according to government statistics, are living in poverty or extreme poverty.

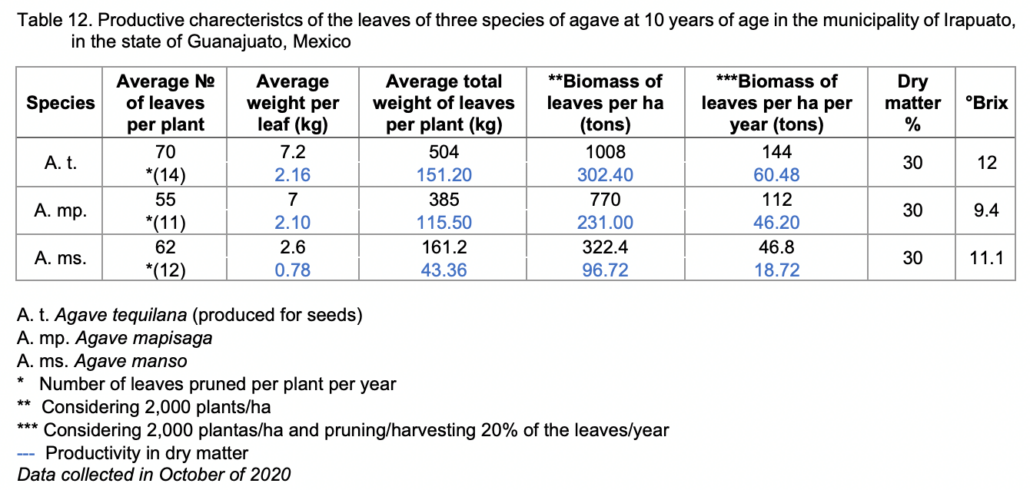

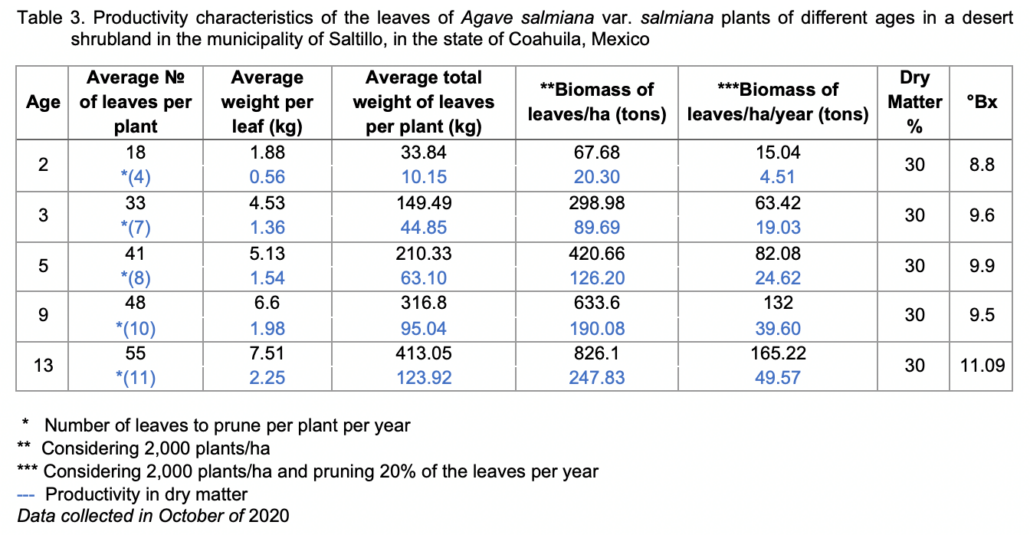

The chart below compares the high productivity of agave (in terms of animal forage or silage production) compared to other forage crops, all of which, unlike agave and mesquite, require expensive and/or unavailable irrigation or crop inputs. The second chart compares the productivity, in terms of penca or leaf biomass, from the species salmiana. See appendix for comparisons of other agave species in a number of different locations.

Deploying the Agave-Based Agroforestry System

The first step in deploying this agave-powered agroforestry and holistic livestock management system involves carrying out basic ecosystem restoration practices. Restoration is necessary given that most dryland areas suffer from degraded soils, erosion, low fertility, and low rainfall retention in soils. Initial ecosystem restoration typically requires putting up fencing or repairing fencing for livestock control, constructing rock barriers (check dams) for erosion control, building up contoured rows and terracing, subsoiling (to break up hardpan soils), transplanting agaves of different varieties and ages (1600-2500 per hectare or 650-1000 per acre), sowing pasture grasses, as well as transplanting (if not previously forested) mesquite or other nitrogen-fixing trees (400 per hectare or 135 per acre) or shrubs. Depending on the management plan, not all agaves will be planted in the same year, but ideally the system contains an equal division of 200 plants per year of each age (planted in ages 1-10) so as to stagger harvest times for the agave piñas, which are harvested at the end of the particular species 8-13 year lifespan.

Planting in turn is followed by no-till soil management (after initial subsoiling) and sowing pasture grasses and cover crops of legumes, meanwhile temporarily “resting” pasture (i.e. keeping animals out of overgrazed pastures or rangelands) long enough to allow regeneration of forage and survival of young agaves and tree seedlings. Following these initial steps of ecosystem restoration and planting agaves and establishing sufficient tree cover, which can take up to five years, the next step is carefully implementing planned rotational grazing of sheep and goats (or other livestock) across these pasturelands and rangelands, at least during the rainy season (4-6 months per year), utilizing moveable solar fencing and/or shepherds and shepherd dogs (neither overgrazing nor under-grazing); supplementing pasture forage, especially during the six-eight-month dry season, with fermented agave silage. During the dry season many families will choose to keep the breeding stock on their smaller family parcels or paddocks, feeding them fermented silage (either agave or agave/mesquite pod mix) to keep them healthy throughout the dry season, when pasture grasses are severely limited.

By implementing these restoration and agroforestry practices, farmers and ranchers can begin to regenerate dryland landscapes and improve the health and productivity of their livestock, provide affordable food for their families, improve their livelihoods, and at the same time, deliver valuable ecosystem services, reducing soil erosion, recharging water tables, and sequestering and storing large amounts of atmospheric carbon in plant biomass and soils, both aboveground and below ground.

Fermenting the Agave Leaves: A Revolutionary Innovation

The revolutionary innovation of a pioneering group of Guanajuato farmers has been to turn a heretofore indigestible, but massive and accessible source of fiber and biomass, the agave leaves or pencas, into a valuable animal feed, utilizing the natural process of anaerobic fermentation to transform the plants’ indigestible saponin and lectin compounds into digestible carbohydrates, sugar, and fiber. To do this, practitioners have developed a relatively simple machine, either stand alone or hooked up to a tractor, that can chop up the very tough pruned leaves of the agave. After chopping the agave’s leaves or pencas (into what looks like green coleslaw) producers then anaerobically ferment this wet silage (ideally along with the chopped-up protein-rich pods of the mesquite tree, or other protein sources) in a closed container, such as a 5 or 50-gallon plastic container or cubeta with a lid, removing as much oxygen as possible (by tapping it down) before closing the lid.

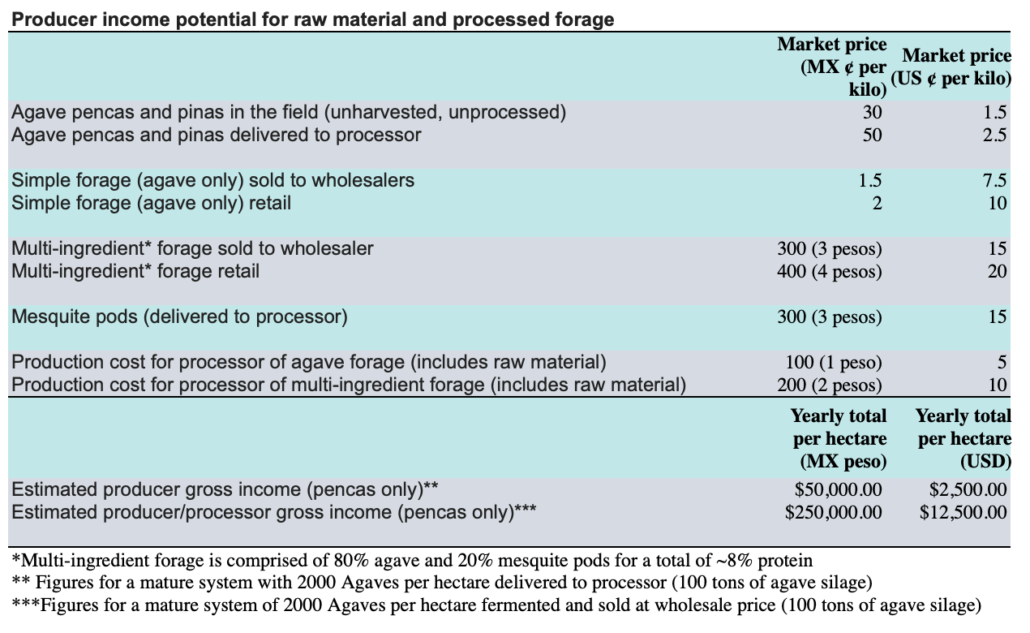

The fermented end-product, golden-colored after 30 days, good for 30 moths, is a nutritious but very inexpensive silage or animal fodder, that costs approximately 1.5 Mexican pesos (or 7.5 cents US) per kilogram/2.2 pounds (fermented agave alone) or three pesos (agave and mesquite pods together) per kilogram to produce. In San Miguel de Allende, the containers we use, during this initial experimental stage of the project cost $3 US per unit for a 20 liter or 5 gallon plastic container or cubeta with a lid, with a lifespan of 25 uses or more before they must be recycled. Two hundred liter reusable containers cost $60 US per unit (new, $30 used) but will last considerable longer than the 20 liter containers.

As the attached business plan for fermented agave silage indicates, harvesting and processing the pencas alone will provide significant value and profits per hectare for landowners and rural communities (such as ejidos in Mexico) who deploy the agave/agroforestry system at scale. In addition, Billion Agave Project researchers are now developing silage storage alternatives that will eliminate the necessity for the relatively expensive 20 liter or 200 liter plastic cubetas or containers.

The agave silage production system can provide the cash-strapped rancher or farmer with an alternative to having to purchase alfalfa (expensive at 20 cents US per kg and water-intensive) or hay (likewise expensive) or corn stalks (labor intensive and nutritionally-deficient), especially during the dry season.

According to Dr. Juan Frias, one of the pioneers of this process, lambs or adult sheep readily convert 10 kilos of fermented agave silage into one kilo of body weight, half of which will be marketable as meat or viscera. At 1.5 to 2 pesos per kilo (7.5-15 cents per pound), this highly nutritious silage can eventually make the difference between poverty and a decent income for literally millions of the world’s dryland small farmers and herders.

Typically, an adult sheep will consume 2-2.5 kilograms of silage every day, while a lamb of up to five months of age will consume 500-800 grams per day. (Cattle will consume 10 times as much silage per day as sheep, approximately 20-25 kg per day.) Under the agave system for sheep and goats it costs approximately 20 pesos or one dollar a pound (live weight) to produce what is worth, at ongoing market rates for non-organic mutton or goat, 40 pesos or two dollars per pound (live weight). (Certified organic lamb, mutton, or goat will bring in 25-50 percent more). In ongoing experiments in San Miguel de Allende, pigs and chickens have remained healthy and productive with fermented agave forage providing 15% of their diet, reducing feed costs considerably.

The bountiful harvest of this regenerative, high-biomass, high carbon-sequestering system includes not only extremely low-cost, nutritious animal forage (up to 100 tons or more per hectare per year of fermented silage, starting in years three-five, averaged out over ten years), but also high-quality organic lamb, mutton, cheese, milk, aquamiel (agave sap), pulque (a mildly alcoholic beverage), inulin (a nutritional supplement), and distilled agave liquor (mescal), all produced organically with no synthetic chemicals or pesticides whatsoever, at affordable prices, with excess agave biomass fiber, and bagasse available for textiles, compost, biochar, construction materials, and bioethanol.

Regenerative Economics: The Bottom Line

In order to motivate a critical mass of impoverished farmers and ranchers struggling to make a living in the degraded drylands of Mexico, or in any of the arid and semi-arid areas in the world, to adopt this system, it is necessary to have a strong economic incentive. There absolutely must be economic rewards, both short-term and long-term, in terms of farm income, if we expect rapid adoption of this system. Fortunately, the agave/mesquite agroforestry system provides this, starting in year three and steadily increasing each year thereafter, producing significant amounts of low-cost silage to feed livestock and a steady and growing revenue stream from selling surplus pencas, piñas, and silage from individual farm or communal lands (ejidos).

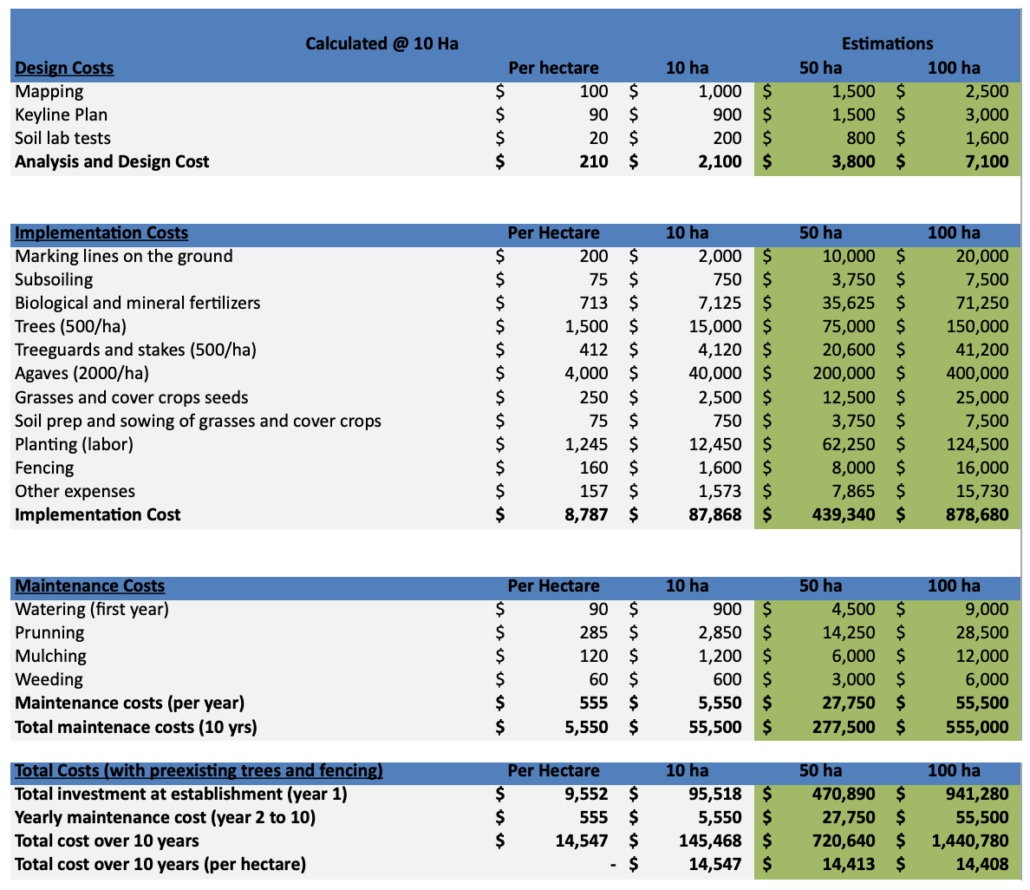

Given that most dryland farmers have little or no operating capital, there needs to be a system to provide financing (loans, grants, ecosystem credits) and technical assistance to deploy this regenerative system and maintain it over the crucial 5-10 year initiation period. Based upon a decade of implementation and experimentation, we estimate that this agave agroforestry system will cost approximately $1500 US dollars per year, per hectare to establish and maintain, averaged out over a ten-year period. See chart below. By year five, however this system should be able to pay out initial operating loans (upfront costs in years one or one through five are much higher than in successive years) and begin to generate a net profit.

The overwhelming majority of Mexican dryland farmers, as noted previously, have no wells for irrigation (86%) and make little no money (90%) from their subsistence agriculture practices (raising corn, beans, and squash and livestock). Although the majority of rural smallholders are low-income or impoverished, they do however typically own their own (family or self-built) houses and farm sheds or buildings as well as title or ownership to their own parcels of land, typically five hectares (12 acres) or less, as well as their livestock. And beyond their individual parcels, three million Mexican families are also joint owners of communal lands or ejidos, which constitute 56% of total national agricultural lands (103 million hectares or 254 million acres). Ejidos arose out the widespread land reform and land redistribution policies following the Mexican Revolution of 1910-20. Large landholdings or haciendas were broken up and distributed to small farmers and rural village organizations, ejidos.

Unfortunately, most of the lands belonging to Mexico’s 28,000 communal landholding ejidos are arid or semi-arid with no wells or irrigation. But being an ejido member does give a family access and communal grazing (some cultivation) rights to the (typically overgrazed) ejido or village communally-owned land. Some ejidos including those in the drylands are quite large, encompassing 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) or more. In contrast to farmers in the US or the rest of the world, most of these Mexican dryland or ejido farmers have little or no debt. For many, their bank account is their livestock, which they sell as necessary to pay for out of the ordinary household and personal expenses.

As noted earlier, most Mexican farmers today subsist on the income from off-farm jobs by family members, and remittances sent home from family members working in the US or Canada. They understand first hand that climate change and degraded soils are making it nearly impossible for them to grow their traditional milpas (raising corn, beans, and squash during the rainy season) or raise healthy livestock for family consumption and sales. Most are aware that their livestock often cost them as much labor and money to raise (or more) than their value for family subsistence or their value in the marketplace.

Mexico has a total of 2400 municipios or counties located in 32 states. Across Mexico small farmers are already cultivating agave or harvesting wild agave in 1000 municipios and nine states, harvesting piñas for mescal or pulque production. Only a few these areas, however, Hacienda Zamarippa in San Luis de la Paz, Via Organica (and surrounding ejidos), a 5,000 hectare organic beef ranch called Canada de la Virgen in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, and pulque producers in Coahuila and Tlaxcala are currently harvesting pencas or agave leaf to produce fermented silage for livestock. However, as the word spreads about the incredible value of pencas and the agave/mesquite agroforestry developing in the state of Guanajuato, farmers in most of the nation’s ejidos and municipios will be interested in deploying this system in their areas.

With start-up financing, operating capital, and technical assistance (much of which can be farmer-to-farmer training), a critical mass of Mexican smallholders should be able to benefit enormously from establishing this agave-based agroforestry and livestock management system on their private parcels, and benefit even more by collectively deploying this system with their other ejido members on communal lands. With the ability to generate a net income up to $6-12,000 US per year/per hectare of fermented agave silage (and lamb/sheep/livestock production) on their lands, low maintenance costs after initial deployment, and with production steadily increasing three to five years after implementation, this agave system has the potential to spread all across Mexico (and all the arid and semi-arid drylands of the world.) As tens of thousands and eventually hundreds of thousands of small farmers and farm families start to become self-sufficient in providing up 100% of the feed and nutrition for their livestock, dryland farmers will have the opportunity to move out of poverty and regenerate household and rural community economies, restoring land fertility and essential ecosystem services at the same time.

The extraordinary characteristic of this agave agroforestry system is that it generates almost immediate rewards. Starting from seedlings or agave shoots, (hijuelos they are called) in year three in the 8-13-year life-span of these agaves, farmers can begin to prune and harvest the lower plant leaves or pencas from these agaves (pruning approximately 20% of leaf biomass every year starting in year three) and start to produce tons of nutritious fermented animal feed/silage. Individual agave leaves or pencas from a mature plant can weigh more than 20 kilos or 45 pounds each. In the areas where wild agaves are growing, (often at fairly low-density of 100-400 agaves per hectare) land managers can detach the shoots from the mother plant and transplant hijuelos, so as to achieve higher (and eventually maximum) density of agaves in the large amount of the nation’s lands where agave are growing wild.

Because the system requires no inputs or chemicals, the meat, milk, or forage produced can readily be certified organic, likely increasing its wholesale value in the marketplace. In addition, the piñas or plant stem from 2000 agave plants (one hectare) with an average piña per plant of 300-400 kg (3 pesos or 15 cents US per KG) can generate a one-time revenue of $52,500 US dollars) at the final harvest of the agave plant, when all remaining leaves and stem are harvested. But even as agaves are completely harvested at the end of their 8-13-year life span, other agave seedlings or hijuelos (shoots) of various ages which have steadily been planted alongside side them will maintain the same level of biomass and silage production. In a hectare of 2,000 agave plants, approximately 72,000 hijuelos or new baby plants (averaging 36 per mother plant) will be produced over a ten-year period. These 72,000 baby plants (ready for transplanting) have a current market value over a ten-year period of 12 Mexico pesos (60 cents US) each or $43,200 US ($4,320 US per year).

Financing the Agave-Based Agroforestry System

Although Mexico’s dryland small-holders are typically debt-free, they are cash poor. To establish and maintain this system, as the chart above indicates, they will need approximately $1500 US dollars a year per hectare ($370 per acre) for a total cost over 10 years at $15,000. Starting in year five, each hectare should be generating $10,000 or more worth of fermented silage or foraje per year.

By year five, farmers deploying the system will be generating enough income from silage production and livestock sales to pay off the entire 10-year loan. From this point on they will become economically self-sufficient, and, in fact, will have the opportunity to become moderately prosperous. Pressure to overgraze communal lands will decrease, as will the pressure on rural people to migrate to cities or to the US and Canada. Meanwhile massive amounts of atmospheric carbon will have begun to be sequestered above ground and below ground, enabling many of Mexico’s 2400 counties (municipalidades) to eventually reach net zero carbon emissions. In addition, other ecosystem services will improve, including reduced topsoil erosion, more rainfall/water retention in soils, more soil organic matter, increased tree and shrub cover, increased biodiversity (above ground and below ground), restoration of grazing areas, and increased soil fertility.

Natural Carbon Sequestration in Regenerated Soils and Plants

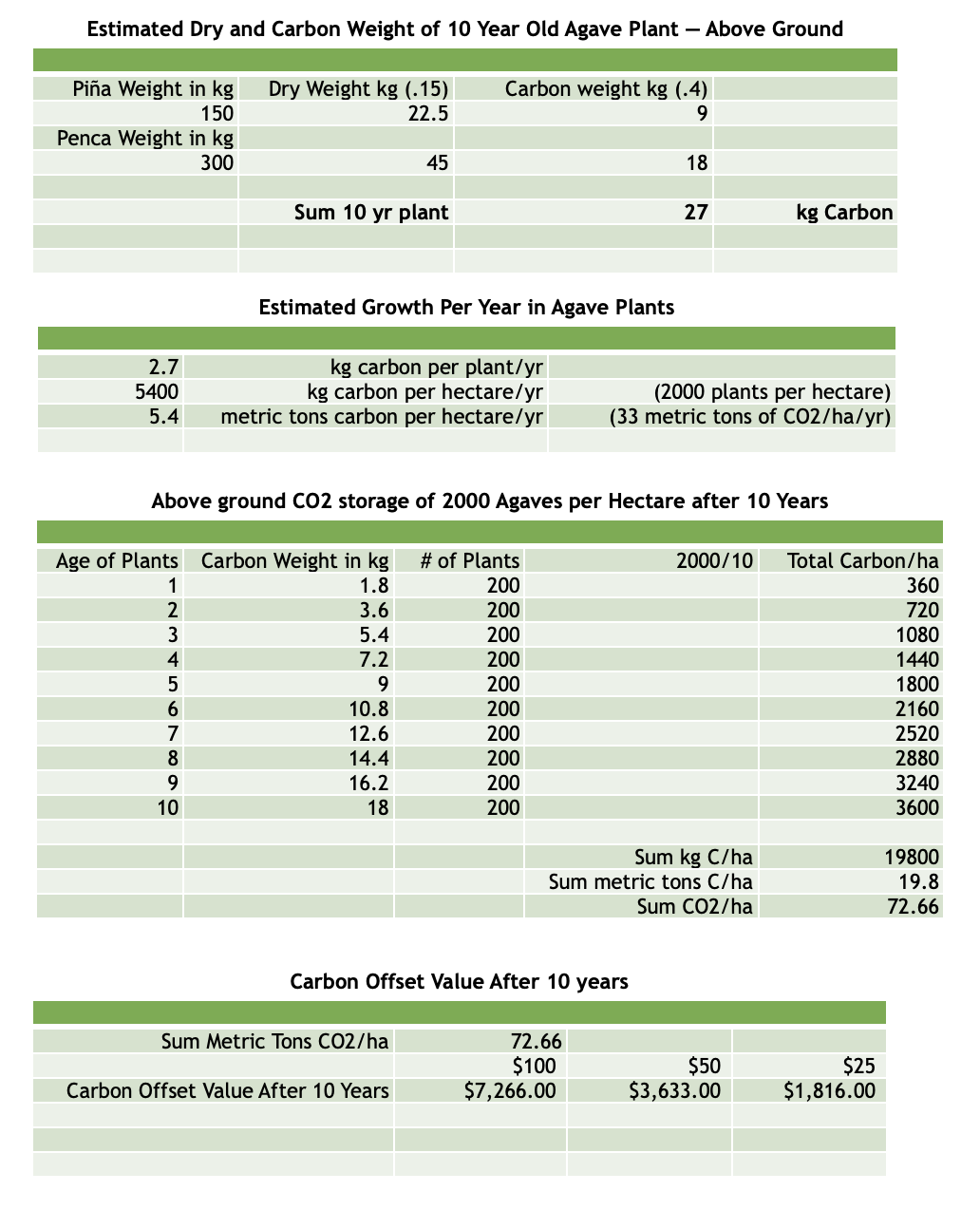

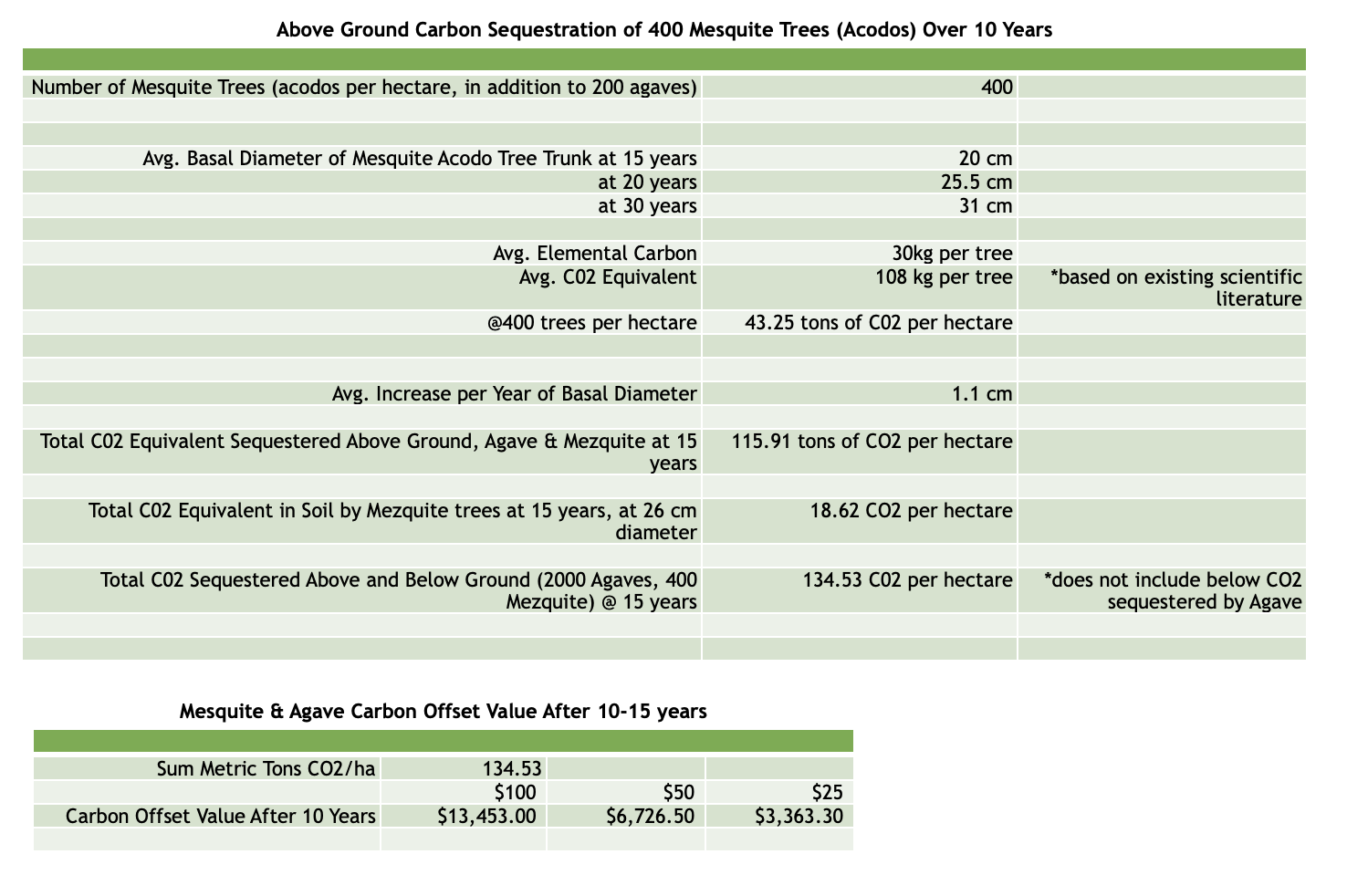

Mexico, like every nation, has an obligation, under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) through converting to renewable forms of energy (especially solar and wind) and energy conservation, at the same time, drawing down excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing, through the process of enhanced forest and plant photosynthesis, this “drawdown” carbon in its biomass, roots, and soil. Agave-based agroforestry (2000 agave plants and 400 mesquite acodos per hectare) as a perennial system, over 10-15 years can store aboveground and below ground approximately 143 metric tons of carbon dioxide per hectare (58 tons of CO2 per acre) on a continuous basis. In terms of this above ground (and below ground) carbon/carbon dioxide sequestration capacity over 10-15 years (143 tons of CO2e), this system, maintained as a polyculture with continuous perennial growth, is among the most soil regenerative on earth, especially considering the fact that it can be deployed in harsh arid and semi-arid climates, on degraded land, basically overgrazed and unsuitable for growing crops, with no irrigation or chemical inputs required whatsoever. In Mexico, where 60% of all farmlands or rangelands are arid or semi-arid, this system has the capacity to sequester 100% of the nation’s current Greenhouse Gas emissions (590 million tons of CO2e) for one year if deployed on approximately 2% or 4.125 million hectares (2000 agaves and 400 mesquites) of the nation’s total lands (197 million hectares). If deployed on 41.25 million hectares, it will cancel out all of Mexico’s GHGs over the next decade. Communally-owned ejido lands in Mexico alone account for more than 100 million hectares. The largest eco-system restoration project in recent until now has been the decade-long restoration of the Loess Plateau (1.5 million hectares) in north-central China in the 1990s.

In a municipalidad or county like San Miguel de Allende, Mexico covering 1,537 Km2 (153,700 hectares) with estimated annual Greenhouse Gas emissions of 654,360 t/CO2/yr (178,300 t/C/yr) the agave/mesquite agroforestry system (sequestering 143 tons of CO2e above ground per hectare after 10 years) would need to be deployed on approximately 4,573 hectares or 3% of the total land in order to cancel out all current emissions for one year. If deployed on 45 thousand hectares it will cancel out all FHG emissions over the next decade. There are 2400 municipalidades or counties in Mexico, including 1000 that are already growing agave and harvesting the piñas for mescal.

In the watershed of Tambula Picachos in the municipality of San Miguel there are 39,022 hectares of rural land (mainly ejido land) in need of restoration (93.4% show signs of erosion, 53% with compacted soil). Deploying the agave/mesquite agroforestry on most of this degraded land 36,150 hectares (93%) would be enough to cancel out all current annual emissions in the municipality of San Miguel for one year.

The gross economic value of growing agave on this 4,573 hectares (including silage, piñas, and hijuelos) averaged out over 10 years would amount to at least $89 million dollars US per year, a tremendous boost to the economy. In comparison, San Miguel de Allende, one of the top tourist destinations in Mexico (with 1.3 visitors annually) brings in one billion dollars a year from tourism, it’s number one revenue generator.

APPENDIX