Best Practices: How Regenerative & Organic Agriculture and Land Use Can Reverse Global Warming

Summary

- The earth’s soils, along with trees and plants, are the largest sink or depository for carbon after the oceans.

- Regenerative organic agricultural practices sequester CO2 and store it in the soil and above ground as organic matter. Perennial polycultures, agroforestry, and reforestation can sustain and increase both above ground and below ground carbon.

- Scaling up a small percentage (5-10%) of best practice regenerative and organic systems will result in billions of tons (Gt) of CO2 per year being sequestered into the soil and into continuous, perennial above ground biomass. The identification, funding, and deployment of these best practices on 5-10% or more of the world’s total croplands (4 billion acres), rangelands (8 billion acres), and forestlands (10 billion acres) will be more than enough to draw down and cancel out all the current CO2 and greenhouse gases (43 Gt of CO2) that are currently being emitted, without putting any more CO2 into the atmosphere or the oceans.

- Currently when carbon dioxide CO2 is released into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels or destructive agriculture or land use practices (currently 43 Gt of CO2 emissions per year), approximately 50% of these 43 Gt of CO2 emissions remain in the atmosphere (21.5 Gt of CO2 annually), while 25% is absorbed by land, plants, and trees (10.75 Gt CO2), and the remainder 25% (10.75 Gt CO2) is absorbed into the ocean. Therefore, we need to begin to draw down 32.25 Gt CO2 (and eventually more) of current total emissions (in conjunction with the conversion to alternative energy and energy conservation), in order to reach net zero emissions (eliminate or cancel out all the emissions going into the atmosphere and the oceans). We will need a net drawdown of 32.75 Gt as soon as possible since 10.75 Gt is already being sequestered by our soils and forests. Once we stop putting more CO2 into the oceans (and the atmosphere), while continuing down the path of alternative energy and regenerative agriculture and land use, the oceans, soils, and biota will be able to draw down evermore significant amounts of the legacy (excess) carbon in the atmosphere, which, in turn, will begin to steadily reduce global warming.

- Regeneration International, a global regenerative and organic agriculture network, with 354 partner organizations in 69 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Oceania, North America and Europe has begun to help publicize global best practices and coordinate the deployment, funding, and scaling up of these systems.

Introduction

Hardly anyone had heard of regenerative agriculture before September 2014, when Regeneration International was founded by a small group of international leaders in the organic, agroecology, holistic management, environment, and natural health movements with the goal of changing the global conversation on climate, farming, and land use. Now the topic of regenerative agriculture is in the news everyday all around the world.

The concept of a coordinated global regeneration movement was initially put forth at the massive Climate Change March in New York, September 22, 2014, at a press conference in the Rodale Institute headquarters. The press conference brought together a global network of like-minded farmers, ranchers, land managers, consumer, and climate activists.

RI’s first General Assembly was held in Costa Rica in 2015 with participants from every continent. In five years Regeneration International has grown with 354 partner organizations in 69 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Oceania, North America and Europe. RI and our allies have been successful in promoting the concept of regenerative agriculture as a game-changing system for ecosystem restoration and sequestering carbon dioxide on a scale and timeline appropriate to our current Climate Emergency.

Why Regenerative Agriculture?

Regenerative agriculture is based on a range of farming, livestock management, and land use practices that utilize the photosynthesis of plants and trees to capture CO2 and store it in the soil and above ground. Regenerative agriculture is now being used as a generic term for the many farming systems that use techniques such as longer rotations, cover crops, green manures, legumes, compost, organic fertilizers, holistic livestock management, and agroforestry. However, Regeneration International believes that true regenerative agriculture must be both organic and regenerative.

Other terms describing regenerative agriculture Include: organic agriculture, agroforestry, agroecology, permaculture, holistic grazing, silvopasture, syntropic farming, pasture cropping and other agricultural systems that can increase soil organic matter/carbon. Soil organic matter is an important proxy for soil health—as soils with low levels are not healthy.

The soil holds almost three times the amount of carbon as the atmosphere and biomass (forests and plants) combined. Long term research shows that soil carbon can be stable for more than 100 years, while appropriate forestry and agroforestry practices can store carbon aboveground on a continuous basis.

Managing climate change is a major issue that we have to deal with now

Atmospheric CO2 levels have been increasing at 2 parts per million (ppm) per year. The level of CO2 reached a new record of 400 ppm in May 2016. However, despite all the commitments countries made in Paris in December 2015, the levels of CO2 increased by 3.3 ppm in 2016 creating a record. It increased by 3.3 ppm from 2018 to set a new record of 415.3 ppm in May 2019. Despite the global economic shut down as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, CO2 levels still set a new record of 417.2 ppm in May 2020. This is a massive increase in emissions per year since the Paris Agreement and shows the reality is that most countries are not even close to meeting their Paris reduction commitments.

Reversing Climate Change

417 ppm far exceeds the Paris objective of limiting the earth’s temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius.

In order to stabilize atmospheric CO2 levels, regenerative agricultural systems will have to drawdown the current increase of emissions of 3.3 ppm of CO2 per year. Using the accepted formula that 1 ppm CO2 = 7.76 Gt CO2 means that, at a minimum, 25.61 gigatons (Gt) of CO2 per year needs to be drawn down from the atmosphere. But in reality we need to drawdown 31.25 Gt of CO2 or more if we want to stop more CO2 from heating up our already overheated oceans and begin to drawdown the legacy 417 ppm CO2 lodged in the atmosphere.

The Potential of “Best Practices” of Regenerative Agriculture

There are numerous regenerative farming systems that can sequester CO2 from the atmosphere through enhanced plant photosynthesis and turn this CO2 into soil organic matter through the actions of the roots and soil biology – the soil microbiome. Others can increase above ground carbon storage through regenerative forest and agroforestry/silvopasture practices. We don’t have time to waste on farming or land use systems that only sequester small amounts of CO2. We need to concentrate on qualitatively scaling up and expanding systems that can achieve high levels of carbon sequestration and ecosystem restoration, systems that are appropriate and scalable for different countries, regions, cultures, and ecosystems.

The simple back of the envelope calculations used for the examples below are a good exercise to show the world-changing potential of these best practice regenerative systems to address the climate emergency and actually start to reverse global warming.

Agave Agroforestry System

The “Billion Agave Project” is a game-changing ecosystem regeneration strategy recently adopted by a growing number of innovative Mexican farms in the high-desert region of Guanajuato, now spreading across Mexico.

This agroforestry system combines the dense cultivation (800 per acre, 2,000 per hectare) of agave plants and nitrogen-fixing companion tree species (such as mesquite), with holistic rotational grazing of livestock. The result is a high-biomass, high forage-yielding system that works well even on degraded, semi-arid lands.

The system produces large amounts of agave leaf and root stem or piña. When chopped and fermented in closed containers, this plant material produces an excellent, inexpensive silage as animal fodder.

Having a large quantity of fermented animal forage on hand reduces the pressure to overgraze brittle rangelands and improves soil health, water retention, and animal health, while drawing down and storing massive amounts of atmospheric CO2 (270 tons of CO2 stored above ground per hectare on a continuous annual basis after 3-10 years.)

The agave agroforestry system can be scaled up across much of the arid and semi-arid regions of the world using native legume trees and grasses, to form highly productive biodiverse agro-forestry systems that are based on the native species of each region. The chopping and fermentation of the legume tree seed pods, such as mesquite (which fix nitrogen and nutrients into the soil), added to the fermented agave, produce a high protein animal fodder superior to alfalfa and at a fraction of the cost, all without the need for any irrigation or synthetic chemicals whatsoever.

Recent research by Hudson Carbon shows that this agave agroforestry system can sequester 270 tons of CO2 per hectare (109 tons per acre) above ground per year on a continuous basis, without counting below ground sequestration nor the amount of carbon sequestered by the (200 per acre) companion trees.

According to the United Nation Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) approximately 40 per cent of the world’s land (4 billion hectares, 10 billion acres) is composed of deserts and drylands, mainly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. These areas sustain over two billion people and supply about 60 per cent of the world’s food production. If the organic and regenerative agave agroforestry system was deployed globally on 10% (400 million hectares) of these 4 billion hectares of arid and semi-arid drylands, it would sequester 10.8 Gt of CO2 per year. This represents approximately 1/3 of the amount of CO2 that needs to be sequestered every year to reverse climate change.

BEAM

BEAM (Biologically Enhanced Agricultural Management), developed by Dr. David Johnson of New Mexico State University, produces organic compost with a high diversity of soil microorganisms, especially fungal material. Multiple crops grown with BEAM have achieved very high levels of sequestration and yields. Research published by Dr. Johnson and colleagues show: “… a 4.5-year agricultural field study promoted annual average capture and storage of 10.27 metric tons’ soil C ha-1 year -1 while increasing soil macro-, meso- and micro-nutrient availability offering a robust, cost effective carbon sequestration mechanism within a more productive and long-term sustainable agriculture management approach.” These results are currently being replicated in other trials.

These figures mean that BEAM can sequester 37,700 kilos (37.7 tons) of CO2 per hectare per year which is approximately 15.3 tons of CO2 per acre.

BEAM can be used in all soil based food production systems including annual crops, permanent crops and grazing systems, including arid and semi-arid regions. If BEAM was deployed globally on just 5 % of all (2.5 billion hectares or 12 billion acres) agricultural lands, it would sequester 9.18 Gt of CO2 per year.

Potential of “No Kill No Till” Bio-intensive Organic

Singing Frogs Farm, located just north of San Francisco, California, is a highly productive No Kill No Till richly biodiverse organic, agroecological horticulture farm on 3 acres. The key to their no till system is to cover the planting beds with mulch and compost instead of plowing them, or using herbicides, and planting directly into the compost, along with a high biodiversity of cash and cover crops that are continuously rotated to break weed, disease and pest cycles.

According to Chico State University they have increased the soil organic matter (SOM) levels by 400% in six years. The Kaisers, the owner/operators of Singing Frogs Farm, have increased their SOM from 2.4% to an optimal 7-8% with an average increase of about 3/4 of a percentage point per year. This farming system is applicable to more than 80% of farms around the world as the majority of farmers have less than 2 hectares (5 acres). If the Singing Frogs farm was extrapolated globally across 5% of arable and permanent crop lands it would sequester 8.9 Gt of CO2/yr.

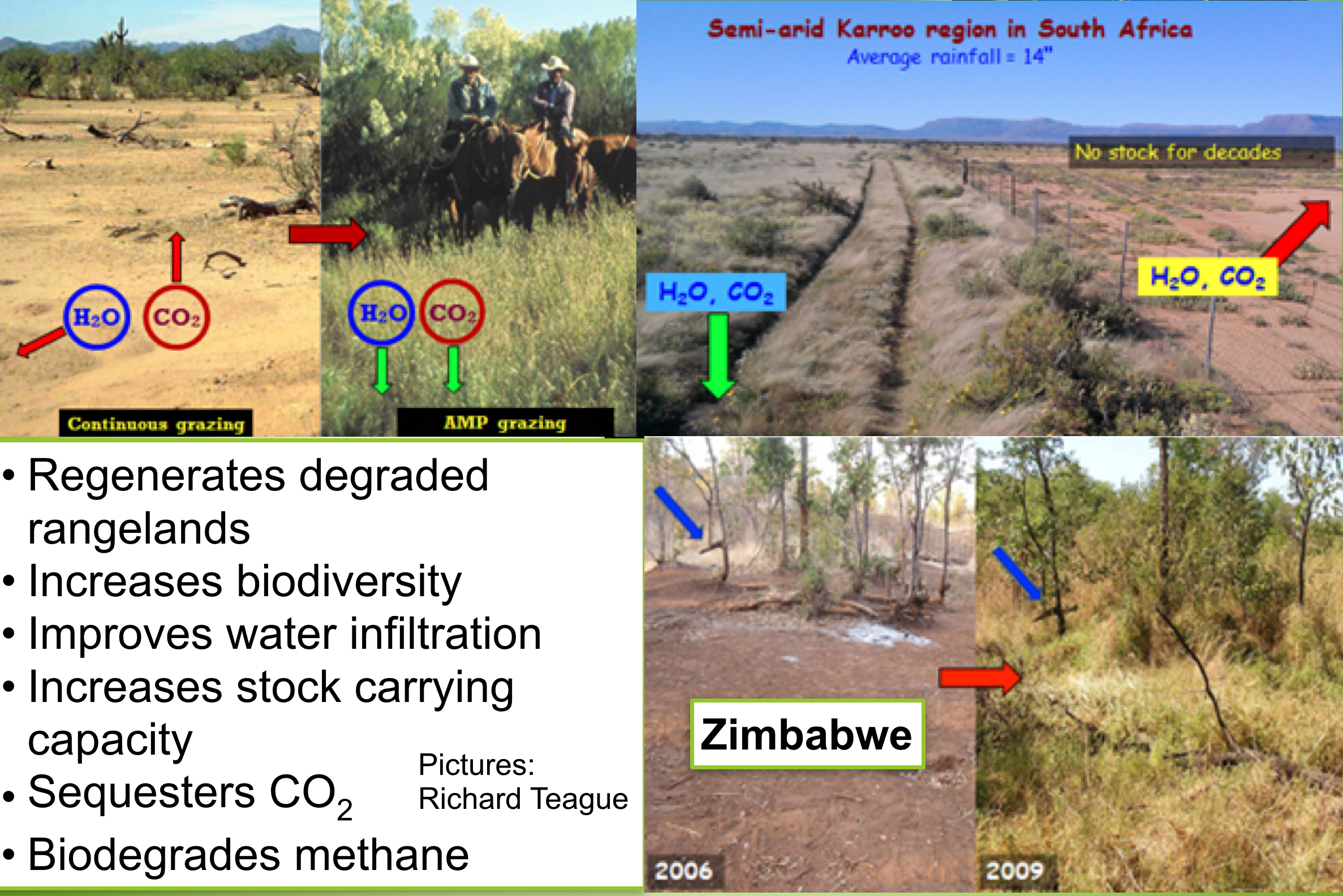

Potential of Regenerative Grazing

There is now a considerable body of published science and evidence based practices showing that regenerative grazing systems can sequester more greenhouse gases than they emit, making them a major solution for reversing climate change.

As well as sequestering CO2, these systems regenerate degraded pasture and rangelands, improve productivity, water holding capacity and soil carbon levels.

Around 68% of the world’s agricultural lands are used for grazing. The published evidence shows that correctly managed pastures can build up soil carbon faster than many other agricultural systems and this is stored deeper in the soil.

Research by published Machmuller et al. 2015: “In a region of extensive soil degradation in the southeastern United States, we evaluated soil C accumulation for 3 years across a 7-year chronosequence of three farms converted to management-intensive grazing. Here we show that these farms accumulated C at 8.0 Mg ha−1 yr−1, increasing cation exchange and water holding capacity by 95% and 34%, respectively.”

The means that they have sequestered 29,360 kilos of CO2 per hectare per year. This is approximately 29,000 pounds of CO2 per acre. If these regenerative grazing practices were implemented on 10 % the world’s grazing lands they would sequester 9.86 Gt of CO2 per year.

Pasture Cropping

Pasture cropping is where the cash crop is planted into a perennial pasture instead of into bare soil. There is no need to plough out the pasture species as weeds or kill them with herbicides before planting the cash crop. The perennial pasture becomes the cover crop.

This was first developed by Colin Seis in New South Wales. The principle is based on the sound ecological fact that annual plants grow in perennial systems. The key is to adapt this principle to the appropriate management system for the specific cash crops and climate.

An excellent example of the development of pasture cropping / no-till no-kill is the Soil Kee, which was designed by Neils Olsen.

First the ground cover/pasture is grazed or mulched to reduce root and light competition. Then the Soil Kee breaks up root mass, lifts and aerates the soil, top-dresses the ground cover/pasture in narrow strips, and plants seeds, all with minimal soil disturbance. The seeds of the cover/cash crops are planted and simultaneously fed an organic nutrient such as guano. The faster the seed germinates and grows, the greater the yield. It is critical to get the biology and nutrition to the seed at germination and to remove root competition.

Pasture cropping is excellent at increasing soil organic matter/soil carbon. Neils Olsen has been paid for sequestering 11 tonnes of CO2 per hectare per year, under the Australian government’s Carbon Farming Scheme in 2019. He was paid for 13 tonnes of CO2 per hectare per year in 2020. He is the first farmer in the world to be paid for sequestering soil carbon under a government regulated system.

If this system were deployed on 10% of all agricultural lands it would sequester 6.38 Gt of CO2 per year.

Global Reforestation

In addition to re-carbonizing and regenerating agricultural lands, a major part of regenerating the Earth and reversing climate change will be to preserve, restore, and expand the world’s 10 billion acres of forests and wetlands. This reforestation and afforestation will include planting up to a trillion tress in deforested areas, as well as several hundred billion trees and perennials back into the world’s four billion acres of cropland (agroforestry) and eight billion acres of pasturelands or rangeland (silvopasture).

The global tree population, which covers 30% of the Earth’s land area, is estimated to be three trillion trees, with 15 billion trees cut down every year. Since humans began farming, 10,000 years ago, approximately half of the trees on Earth have been cut down and not replanted. The Earth’s forests and wetlands now sequester over 700 billion tons of carbon, and currently draw down, even with massive deforestation and forest fires taken into account, an additional “net sink” of 1.2 gigatons of carbon. (White, Biosequestration and Biological Diversity, p.101) The net sink or carbon sequestration power of today’s forests amounts to approximately 12% of all current human emissions.

If “net deforestation” (more tress being cut down, clear-cut, or burned than the amount of healthy and new tree growth) could be halted in forested areas, especially in tropical areas where the trees grow faster and store the most carbon, and forests worldwide could be managed to increase photosynthesis and biomass through massive reforestation (and by thinning out crowded forest areas with thousands of trees per acre to hundreds of the healthiest and largest trees per acre), the world’s forests could net sequester four billion tons or more of atmospheric carbon a year, a full 40% of all current human emissions. Along with renewable energy and carbon farming, If we stop deforestation and reforest the Earth with an a trillion, species-appropriate trees, and then maintain these trees, we can literally reverse global warming.

The United Nations Environmental Project (UNEP) has now announced a new goal for global reforestation and carbon sequestration called the “Trillion Tree Campaign.” The UN points out that there is enough deforested or empty space in rural and urban areas to plant a trillion trees on the planet of which 600 billion mature trees can be expected to survive. And this trillion tree planting campaign does not include the additional 100 billion-plus trees that could and should be planted on the Earth’s 12 billion acres of croplands and pastures utilizing the tried-and-proven carbon sequestering, livestock friendly, fertility-enhancing techniques of agroforestry and silvopasture. UNEP warns however that there are “170 billion trees in imminent risk of destruction,” that must be protected for crucial carbon storage and biodiversity protection.

According to UNEP, “Global reforestation could capture 25 percent of global annual carbon emissions and create wealth in the global south.” More than 13.6 billion trees have already been planted as part of the Trillion Tree Campaign, which analyzes and projects, not only where trees have been planted, but also the vast areas where forests could be restored.

The UN’s Trillion Tree Campaign is inspired in part by a recent study by Dr. Thomas Crowther and others, integrating data from ground-based surveys and satellites, that found that replanting the world’s forests (an additional 1.2 trillion trees) on a massive scale in the empty spaces in forests, deforested areas, and degraded and abandoned land across the planet would draw down 100 billion tons of excess carbon from the atmosphere.

According to Crowther: “There’s 400 gigatons now, in the 3 trillion trees, and if you were to scale that up by another trillion trees that’s in the order of hundreds of gigatons captured from the atmosphere – at least 10 years of anthropogenic emissions completely wiped out… [trees are] our most powerful weapon in the fight against climate change,” he said.

And Crowther’s projections (10 years or 450 Gt of CO2 emissions that can be sequestered via global reforestation) do not include the massive amount of carbon drawdown and sequestration we can achieve through agroforestry and silvopasture practices, planting trees, if only a few trees per acre, on the US and the world’s often deforested 4 billion acres of croplands and 8 billion acres of pasturelands, rangelands, and pastures.

Ending the Climate Emergency- Scaling Up

Regeneration International has 354 partner organizations in 69 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Oceania, North America and Europe. This gives us the ability work with our partner organizations on every arable continent to develop and scale up appropriate regenerative agricultural solutions for multiple countries and regions.

Transitioning a small proportion (10%) of global agricultural production to these evidence based, best-practice, regenerative systems will sequester enough CO2 to reverse climate change and restore the global climate, especially in conjunction with an aggressive global reforestation program such as the Trillion Tree Campaign.

If the RI-sponsored organic and regenerative agave agroforestry system is deployed globally on 10% (400 million hectares) of arid and semi-arid drylands, it will sequester 10.8 Gt of CO2 per year.

Five percent of global agricultural lands regenerated by the BEAM organic compost system can sequester 9.18 Gt of CO2 per year.

Five percent of small holder farms across arable and permanent crop lands using Singing Frogs Farm’s biointensive organic No Kill No Till systems could sequester 8.9 Gt of CO2/yr.

Ten percent of grasslands under regenerative grazing could sequester 9.86 Gt of CO2 per year.

10% of agricultural lands using pasture cropping could sequester 6.38 Gt of CO2 per year.

The deployment of all of these regenerative and organic best practices across the world on 5-10% of all agricultural lands (including arid and semi-arid lands where raising crops and grazing animals are increasingly problematic) would result in 45.12 Gt of CO2 per year being sequestered into the soil, and stored aboveground on a continuous basis, which is 50% more than the amount of sequestration needed to drawdown the 31.25 Gt of CO2 that is currently being released into the atmosphere and the oceans. And this does not include the massive CO2 sequestration that is possible under the Trillion Tree Campaign.

These back of the envelope calculations are designed to show the considerable potential of scaling up proven high performing regenerative systems. The examples are ‘shovel ready’ solutions as they are based on existing practices. There is no need to invest in expensive, potentially dangerous and unproven technologies such as carbon capture and storage or geo-engineering.

Aiming to achieve 5-10% adoption rates for these regenerative and organic practices across the globe is realistic and achievable. The critical priorities are to educate consumers and build market demand, identify and promote regenerative best practices in all the countries and regions of the world, change public policies wherever possible (from the local to the international level) and then fund (through private and public money), expand, and scale up these regenerative and organic systems to restore ecosystems, sequester carbon, regenerate public health and eliminate rural poverty.

It is time to get on with restoring global ecosystems and drawing down excess CO2 by scaling up the existing “best practices” regenerative agriculture, livestock management, forest practices, and land use. All of this is very doable and achievable. It will require substantial investment in natural capital from existing private and public funders and national and international institutions, but it is obviously “worth the cost” compared to the business as usual of our current “suicide economy.” It will require training organizations and relevant NGOs to run courses and workshops from Main Street to the Middle East and beyond, scaled up through grassroots-powered farmer to farmer training systems, and supported by urban consumers across the world. The hour is late. But there is still time to turn things around.

The widespread adoption of best practice regenerative and organic practices should be the highest priority for farmers, ranchers, governments, international organizations, elected representatives, industry, training organizations, educational institutions and climate change organizations. We owe this to future generations and to all the rich biodiversity on our precious living planet.

References/sources:

Johnson D, Ellington J and Eaton W, (2015) Development of soil microbial communities for promoting sustainability in agriculture and a global carbon fix, PeerJ PrePrints | http://dx.doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.789v1 | CC-BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 13 Jan 2015, publ: 13 Jan 2015

Jones C, (2009) Adapting farming to climate variability, Amazing Carbon, www.amazingcarbon.com

Lal R (2008). Sequestration of atmospheric CO2 in global carbon pools. Energy and Environmental Science, 1: 86–100.

Kulp SA & Strauss BH (2019), New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding, Nature Communications, (2019)10:4844, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z, www.nature.com/naturecommunications

McCosker, T. (2000). “Cell Grazing – The First 10 Years in Australia,” Tropical Grasslands. 34: 207-218.

Machmuller MB, Kramer MG, Cyle TK, Hill N, Hancock D & Thompson A (2014). Emerging land use practices rapidly increase soil organic matter, Nature Communications 6, Article number: 6995 doi:10.1038/ncomms7995, Received 21 June 2014 Accepted 20 March 2015 Published 30 April 2015

NOAS (2017). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (US)

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/how-much-will-earth-warm-if-carbon-dioxide-doubles-pre-industrial-levels, Accessed Jan 30 2017

Rohling EJ, K. Grant, M. Bolshaw, A. P. Roberts, M. Siddall, Ch. Hemleben and M. Kucera (2009) Antarctic temperature and global sea level closely coupled over the past five glacial cycles, Nature Geoscience, advance online publication, www.nature.com/naturegeoscience

Spratt D and Dunlop I, 2019, Existential climate-related security risk: A scenario approach, Breakthrough – National Centre for Climate Restoration, Melbourne, Australia

www.breakthroughonline.org.au, May 2019 Updated 11 June 2019

https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/148cb0_90dc2a2637f348edae45943a88da04d4.pdf

Tong W, Teague W R, Park C S and Bevers S, 2015, GHG Mitigation Potential of Different Grazing Strategies in the United States Southern Great Plains, Sustainability 2015, 7, 13500-13521; doi:10.3390/su71013500, ISSN 2071-1050, www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability

UNCCD, 2017, The Global Land Outlook 2017, Secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification Platz der Vereinten Nationen 153113 Bonn, Germany

https://knowledge.unccd.int/sites/default/files/2018-06/GLO%20English_Full_Report_rev1.pdf

Global Agricultural Land Figures

United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), FAOSTAT data on land use, retrieved December 4, 2015

The total amount of land used to produce food is 4,911,622,700 Hectares (18,963,881 square miles).

This is divided into:

Arable/Crop land: 1,396,374,300 Hectares (5,391,431 square miles)

Permanent pastures: 3,358,567,600 Hectares (12,967,502 square miles)

Permanent crops: 153,733,800 Hectares (593,570 square miles)

The Billion Agave Project Calculations

According to the UNCCD The Global Land Outlook 2017, almost 45 per cent of the world’s agricultural land is located on drylands, mainly in Africa and Asia.

45% of croplands (4,911,622,700 ha x 45%) = 2.2 billion Hectares

2.2 x 270 tons of CO2 per ha = 594 Gt of CO2 per year

BEAM Calculations

A basic calculation shows the potential of scaling up this simple technology across the global agricultural lands. Soil Organic Carbon x 3.67 = CO2 which means that 10.27 metric tons soil carbon = 37.7 metric tons of CO2 per hectare per year (t CO2/ha/yr). This means BEAM can sequester 37.7 tons of CO2 per hectare which is approximately 38,000 pounds of CO2 per acre.

If BEAM was extrapolated globally across agricultural lands it would sequester 185 Gt of CO2/yr. (37.7 t CO2/ha/yr X 4,911,622,700 ha = 185,168,175,790t CO2/ha/yr)

Singing Frogs Farm Calculations

The Kaisers have managed to increase their soil organic matter from 2.4% to an optimal 7-8% in just six years, an average increase of about 3/4 of a percentage point per year (Elizabeth Kaiser Pers. Com. 2018 and Chico State University https://www.csuchico.edu/regenerativeagriculture/demos/singing-frogs.shtml

“An increase of 1% in the level of soil carbon in the 0-30cm soil profile equates to sequestration of 154 tCO2/ha if an average bulk density of 1.4 g/cm3” (Jones C. 2009)

3/4 % OM = 115.5 metric tons of CO2 per hectare (115,500 pounds an acre per year)

This system can be used on arable and permanent crop lands. Arable/Crop land: 1,396,374,300 Hectares plus Permanent crops: 153,733,800 Hectares = 1,550,108,100 Hectares

Extrapolated globally across arable and permanent crop lands it would sequester 179 Gt of CO2/yr (1,550,108,100 Hectares x 115.5 metric tons of CO2 per hectare = 179,037,485,550 metric tons)

Regenerative Grazing Calculations

To explain the significance of Machmuller’s figures: 8.0 Mg ha−1 yr−1 = 8,000 kgs of carbon being stored in the soil per hectare per year. Soil Organic Carbon x 3.67 = CO2, which means that these grazing systems have sequestered 29,360 kgs (29.36 metric tons) of CO2/ha/yr. This is approximately 30,000 pounds of CO2 per acre.

If these regenerative grazing practices were implemented on the world’s grazing lands they would sequester 98.6 Gt CO2/yr.

(29.36t CO2/ha/yr X 3,358,567,600 ha = 98,607,544,736t CO2/ha/yr)

Pasture Cropping Calculations

Agricultural lands 4,911,622,700 ha x 13t CO2/ha/yr = 63.8 Gt of CO2 per year

Global Reforestation Calculations

Andre Leu is the International Director for Regeneration International. To sign up for RI’s email newsletter, click here.

Ronnie Cummins is co-founder of the Organic Consumers Association (OCA) and Regeneration International. To keep up with RI’s news and alerts, sign up here.