Agroecological Approaches to Enhance Resilience Among Small Farmers

Authors: Clara Inés Nicholls and Miguel Altieri | Published: June 26, 2017

Many studies reveal that small farmers who follow agroecological practices cope with, and even prepare for, climate change. Through managing on-farm biodiversity and soil cover and by enhancing soil organic matter, agroecological farmers minimise crop failure under extreme climatic events.

Global agricultural production is already being affected by changes in rainfall and temperature thus compromising food security. Official statistics predict that small scale farmers in developing countries will be especially vulnerable to climate change because of their geographic exposure, low incomes, reliance on agriculture and limited capacity to seek alternative livelihoods.

Although it is true that extreme climatic events can severely impact small farmers, available data is just a gross approximation at understanding the heterogeneity of small scale agriculture, ignoring the myriad of strategies that thousands of small farmers have used, and still use, to deal with climatic variability.

Observations of agricultural performance after extreme climatic events reveal that resilience to climate disasters is closely linked to the level of on-farm biodiversity. Diversified farms with soils rich in organic matter reduce vulnerability and make farms more resilient in the long-term. Based on this evidence, various experts have suggested that reviving traditional management systems, combined with the use of agroecological principles, represents a robust path to enhancing the resilience of modern agricultural production.

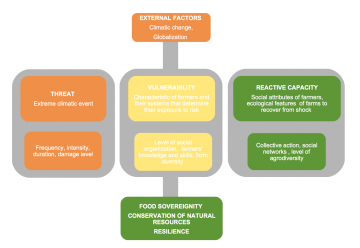

factors that determine the degree of

resilience to climatic, and other, shocks.

Diverse farming systems

A study conducted in Central American hillsides after Hurricane Mitch showed that farmers using diversification practices (such as cover crops, intercropping and agroforestry) suffered less damage than their conventional monoculture neighbours. A survey of more than 1800 neighbouring ‘sustainable’ and ‘conventional’ farms in Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala, found that the ‘sustainable’ plots had between 20 to 40% more topsoil, greater soil moisture and less erosion, and also experienced lower economic losses than their conventional neighbours. Similarly in Chiapas, coffee systems exhibiting high levels of diversity of vegetation suffered less damage from farmers to produce various annual crops simultaneously and minimise risk. Data from 94 experiments on intercropping of sorghum and pigeon pea showed that for a particular ‘disaster’ level quoted, sole pigeon pea crop would fail one year in five, sole sorghum crop would fail one year in eight, but intercropping would fail only one year in 36. Thus intercropping exhibits greater yield stability and less productivity decline during drought than monocultures.

At the El Hatico farm, in Cauca, Colombia, a five story intensive silvo-pastoral system composed of a layer of grasses, Leucaena shrubs, medium-sized trees and a canopy of large trees has, over the past 18 years, increased its stocking rates to 4.3 dairy cows per hectare and its milk production by 130%, as well as completely eliminating the use of chemical fertilizers. 2009 was the driest year in El Hatico’s 40-year record, and the farmers saw a reduction of 25% in pasture biomass, yet the production of fodder remained constant throughout the year, neutralising the negative effects of drought on the whole system. Although the farm had to adjust its stocking rates, the farm’s milk production for 2009 was the highest on record, with a surprising 10% increase compared to the previous four years. Meanwhile, farmers in other parts of the country reported severe animal weight loss and high mortality rates due to starvation and thirst.

Enhancing soil organic matter

Adding large quantities of organic materials to the soil on a regular basis is a key strategy used by many agoecological farmers, and is especially relevant under dryland conditions. Increasing soil organic matter (SOM) enhances resilience by improving the soil’s water retention capacity, enhancing tolerance to drought, improving infiltration, and reducing the loss of soil particles through erosion after intense rains. In long-term trials measuring the relative water holding capacity of soils, diversified farming systems have shown a clear advantage over conventional farming systems. Studies show that as soil organic matter content increases from 0.5 to 3%, available water capacity can double.

At the same time, organically-rich soils usually contain symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi, such as vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal (VAM) fungi, which are a key component of the soil microbiota, influencing plant growth and soil productivity. Of particular significance is the fact that plants colonised by VAM fungi usually exhibit significantly higher biomass and yields compared to non-mycorrhizal plants, under water stress conditions. Mechanisms that may explain VAM-induced drought tolerance, and increased water use efficiency involve both increased dehydration avoidance and dehydration tolerance.

Managing soil cover

Protecting the soil from erosion is also a fundamental strategy for enhancing resilience. Cover crop mulching, green manures and stubble mulching protects the soil surface with residues and inhibits drying of the soil. Mulching can also reduce wind speed by up to 99%, thereby significantly reducing losses due to evaporation. In addition, cover crop and weed residues can improve water penetration and decrease water runoff losses by two to six times.

Throughout Central America, many NGOs have promoted the use of grain legumes as green manures, an inexpensive source of organic fertilizer and a way of building up organic matter. Hundreds of farmers along the northern coast of Honduras are using velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens) with excellent results, including corn yields of about 3 tonne/ha, more than double the national average. These beans produce nearly 30 tonne/ha of biomass per year, adding about 90 to 100 kg of nitrogen per hectare per year to the soil. The system diminishes drought stress, because the mulch layer left by Mucuna helps conserve water in the soil, making nutrients readily available in periods of major crop uptake.

Today, well over 125,000 farmers are using green manures and cover crops in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Hillside family farmers modified the conventional no-till system by leaving plant residues on the soil surface. They noticed a reduction in soil erosion levels, and also experienced lower fluctuations in soil moisture and temperature. These novel systems rely on mixtures for summer and winter cover cropping which leave a thick residue on which crops like corn, beans, wheat, onions or tomatoes are directly sown or planted, suffering very little weed interference during the growing season. During the 2008-2009 season, when there was a severe drought, conventional maize producers experienced an average yield loss of 50%, reaching productivity levels of 4.5 tonne/ha. However the producers who had switched to no-till agroecological practices experienced a loss of only 20%, confirming the greater resilience of these systems.