Author: Jess Daniels | Published: May 3, 2017

This year’s Fashion Revolution Week just wrapped up but the movement for transparency, accountability, and shifting the norms of a harmful and wasteful industry is gaining more traction and momentum than ever.

Born out of tragedy, the Fashion Revolution campaign began with just one day and one question to honor the nearly 1200 lives lost and innumerable others forever changed when the Rana Plaza Factory collapsed due to structural damages ignored by management, causing the greatest garment worker disaster in history. Because fashion is a consumer-based industry, the burden falls not only in the hands of the corporations contracting with clothing manufacturers but on all of us who make choices each time we shop, choices to unwaveringly support a supply chain, or to question its impacts and motivations, or to pursue a more just and ecologically sound path.

Since 2013 it seems a call to action has reverberated through the fashion industry and through so many of us who have awoken to the recognition of our role as wearers of clothing.

Photo: Modeling regenerative fashion with the Grow Your Jeans project, by Paige Green Photography.

Photo: Modeling regenerative fashion with the Grow Your Jeans project, by Paige Green Photography.

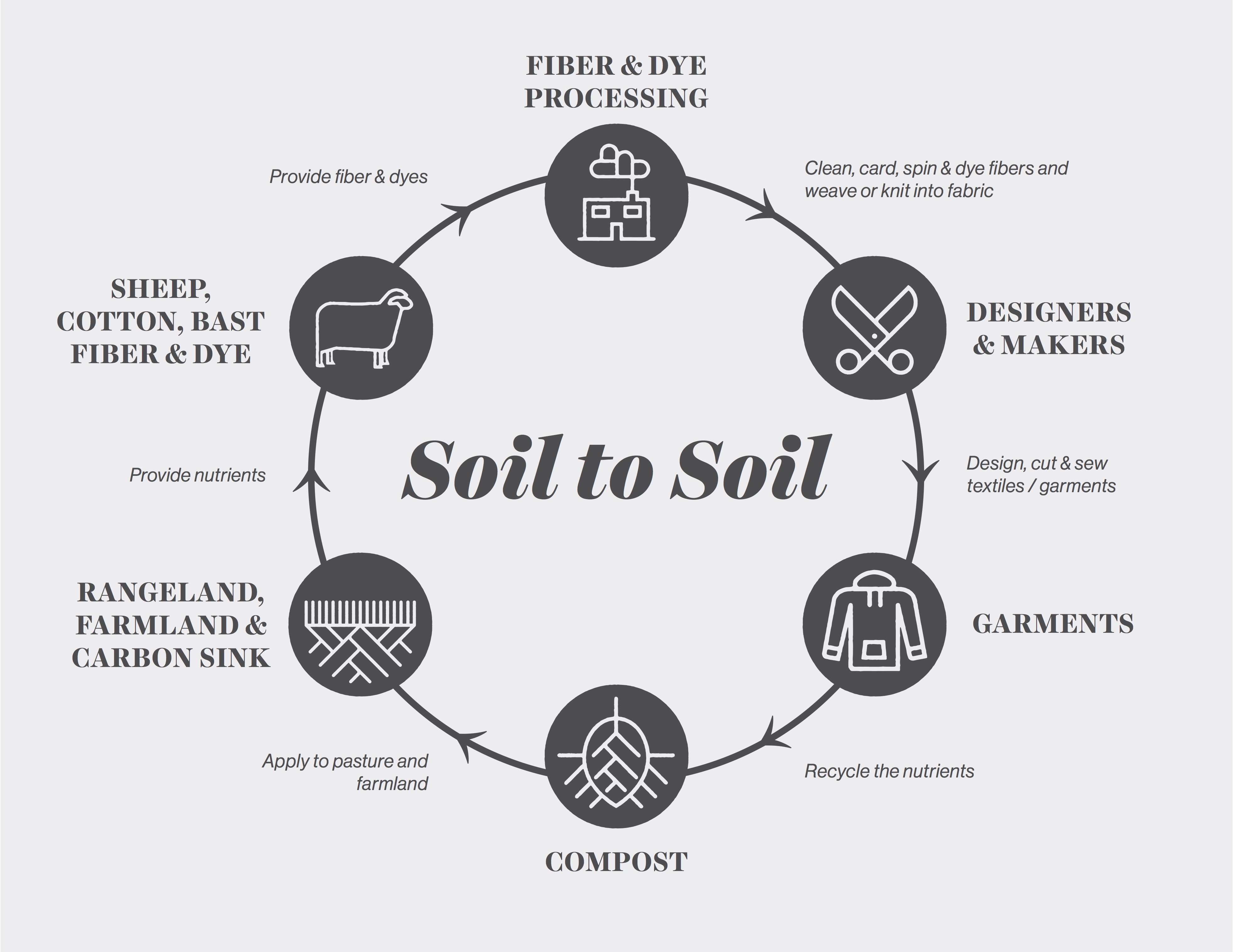

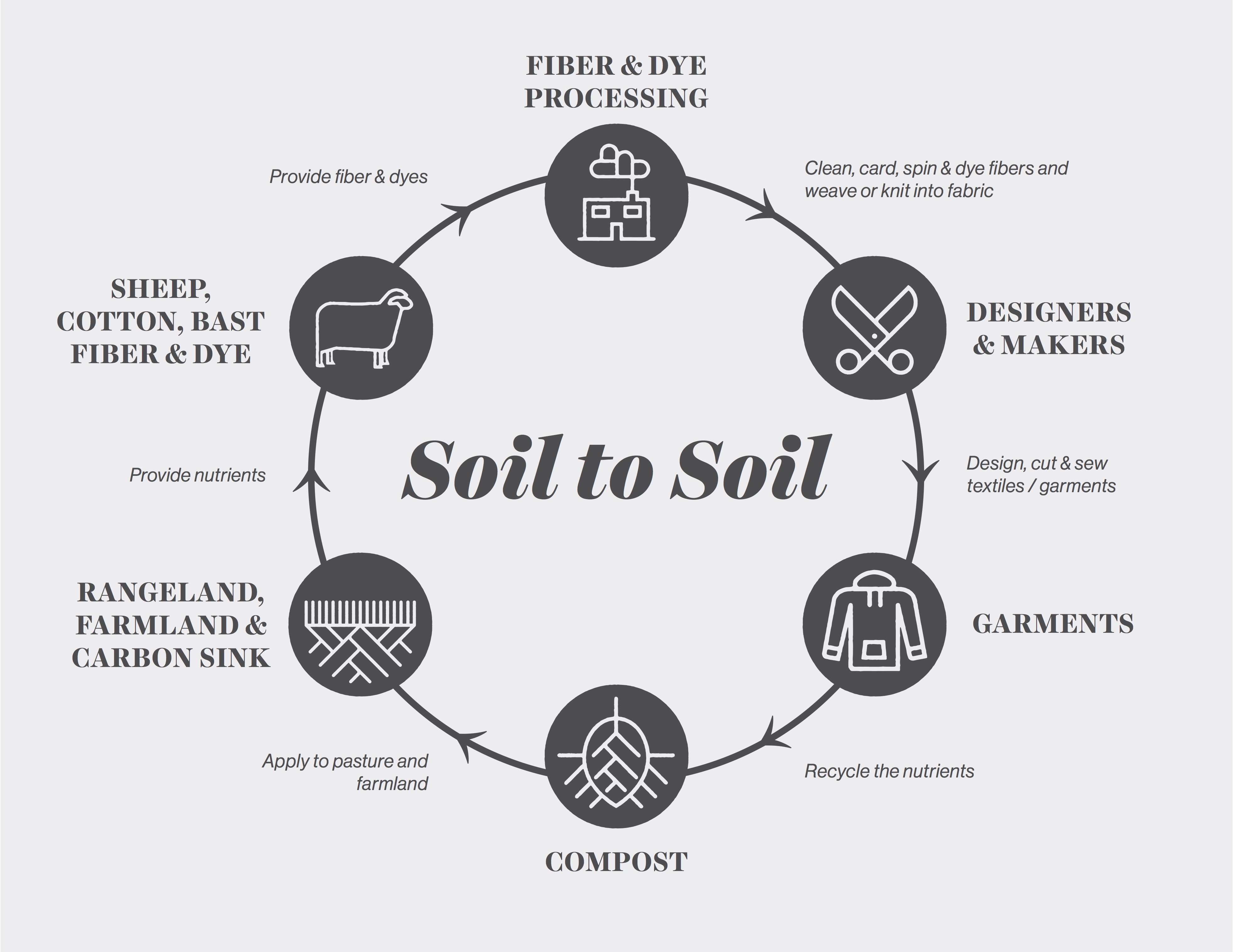

Here in the Fibershed community, we have seen our Northern California community flourish with a fashion show that re-envisions denim as a place-based and fossil-fuel-free garment; we have supported the shift of the world’s largest textile corporation in creating their first ‘re-shored’ supply chain right here in their own backyard; we have nurtured the swell of the soil to soil movement in over 50 Fibershed Affiliate communities worldwide; and we have created an economic model for funding on-farm climate solutions through community-powered textile programs.

It’s hard to become aware of the issues, or even one aspect of the impacts, of modern fashion and not be discouraged. For an industry that relies on agriculture, manufacturing, shipping & transport, washing, waste and recycling systems – sectors that all told account for 59% of global greenhouse gas emissions¹ – we can’t even definitively say exactly how bad fashion is for the climate.

We need more research and life cycle assessments and internalization of the carbon cost of clothing, but here is an early indicator of how deep & far-reaching this industry goes: recent studies show that synthetic microfiber pollution is 131 times worse than initially reported (just 6 years ago)² – this microscopic pollution amounts to two hundred million microfibers per person on earth, and more by the second. Yes, as I’m typing this or you’re reading this, our poly-cotton t-shirts or spandex-blend yoga pants or feel-good recycled fleeces are shedding into our washing machines and heading out into waterways. A tip of the proverbial iceberg (which, unfortunately, also contains plastic fibers).

Yet consider that this research, despite its relatively short-lived publication, has spawned the start of creative solutions. From microfiber-trapping laundry balls to differences in material development to industrial filters, we’re seeing pragmatic and iterative options along the supply chain.

Photo: regional supply chain partner and Fibershed member Huston Textile Co., by Paige Green Photography

Photo: regional supply chain partner and Fibershed member Huston Textile Co., by Paige Green Photography

Climate scientists say that one of the most difficult challenges in addressing climate change is that humans have a hard time understanding things we haven’t experienced³. Our species has a hard time tackling the unimaginable, and perhaps that’s why it took a heartbreaking disaster to bring forth the Fashion Revolution. Maybe that’s why studies and video campaigns about microfibers – a pollution problem so big yet so microscopic it’s invisible – are leading the way for solutions engineering.

So if we don’t know precisely how to encompass and measure fashion’s climate footprint, let’s focus on a few key pieces we do know. We know that natural fibers not only eliminate the microfiber-shedding pollution created by synthetics (which will never biodegrade), and that natural fibers begin with the soil instead of with fossil fuels extracted from the earth. Right now we have tipped the scales so that the majority of the world’s fibers are made from plastic, which is made from fossilized carbon stocks, the release of which directly contributes to climate change.

Photo: rebuilding soil with compost application, by Paige Green Photography

Photo: rebuilding soil with compost application, by Paige Green Photography

We know that topsoil is degraded on working lands around the world*, but that there are strategies and practices that use natural systems instead of chemical inputs to build soil health. And we know that these practices, with proper planning and management, can even increase soil carbon, meaning that they help mitigate climate change.

For instance: the carbon farm plan from one of our members has calculated that soil-building practices will offset greenhouse emissions equivalent to taking 180 cars off the road each year in perpetuity.

And we know that such working lands, in our Fibershed and around the world, can produce incredible natural fibers, from naturally colored cotton to next-to-skin soft wool, sturdy bast fibers like hemp and flax linen, luxurious alpaca and other fine fibers, and coarse wool that makes cozy bedding and durable goods. With fibers in hand, there are still mills across the US that can serve as supply chain partners and avoid transcontinental shipping, and by blending different natural fibers we can create textiles with amazing material properties that keep us warm in the winter, cool in the summer, allow our skin to breath, and that last a long time in our wardrobe or home.

Photo: in the indigo research plot, harvsting regional natural dyes, by Paige Green Photography

Photo: in the indigo research plot, harvsting regional natural dyes, by Paige Green Photography

While we know that most synthetic dyes cause harm to our waterways and endocrine system**, we see a growing community of natural dyeing teachers, practitioners, and innovators who are growing, foraging, and making color that honors place (our indigo project, Artisan Producer directory, and community events calendar are great places to start connecting).

With the Fashion Revolution campaign encouraging all to ask ‘Who Made My Clothes?’ we see more avenues for transparency, accountability, and education coming online.

Consumer care processes are actually 23% of the carbon footprint of a piece of clothing***, and we see consumers engaging with the supply chain and becoming prosumers – caring about proper washing, altering, mending, and wearing items for longer – we know more and more how vast textile waste is — with an average of 70 lbs per person each year heading to landfill — and both individuals and brands are addressing it by buying less or upcycling materials. Finally, we know students, artisans, and brands from small to large, are designing for change – looking at the full circular economy of clothing and anticipating a return to the landscape instead of a trip to the landfill when worn out.

Photo: Peggy Sue Collection 2017, via Peggy Sue Collection

Photo: Peggy Sue Collection 2017, via Peggy Sue Collection

With the Fashion Revolution underway, we need to dig down to the soil level. We need to ask deeper questions of brands and ourselves about each material ingredient and process throughout the life of a garment; we need scientists and activists to take the fashion industry seriously as a contributor to global climate change, and we need to invest in Climate Beneficial systems.

Let’s also extend the Fashion Revolution beyond one day or week of the year: we invite you to get to know your fibershed firsthand, to get to know a fiber farmer or take a natural dyeing class or become a prosumer by knitting a local shawl or making an outfit that’s grown and sewn close to home. If we struggle to take collective action to combat climate change because we can’t quite envision its impacts, or because our political climate refuses to address it, we know we can root ourselves in the soil, build community through educational and economic relationships, and take part in revolutionizing fashion from the ground up with our very own hands, together.

Jess Daniels provides research, communications strategy, and project management for Fibershed. She coordinates the Fibershed Affiliate Network and is an avid maker and explorer of slow fashion.

Re-posted with permission from Fibershed. See the original article here.

Photo: Modeling regenerative fashion with the Grow Your Jeans project, by Paige Green Photography.

Photo: Modeling regenerative fashion with the Grow Your Jeans project, by Paige Green Photography. Photo: regional supply chain partner and Fibershed member Huston Textile Co., by Paige Green Photography

Photo: regional supply chain partner and Fibershed member Huston Textile Co., by Paige Green Photography Photo: rebuilding soil with compost application, by Paige Green Photography

Photo: rebuilding soil with compost application, by Paige Green Photography Photo: in the indigo research plot, harvsting regional natural dyes, by Paige Green Photography

Photo: in the indigo research plot, harvsting regional natural dyes, by Paige Green Photography Photo: Peggy Sue Collection 2017, via

Photo: Peggy Sue Collection 2017, via