Who Grew Our Clothes?

Author: Rebecca Burgess | Published: April 24, 2016

Unraveling the story behind the glamor and surface appeal of fast fashion is like Dorothy and her little dog toto pulling the curtain back on the man whose amplified voice is used to create the illusion of the Wizard of Oz. The fervor and pomp of fast fashion lies in contrast to the landscapes from which it comes. It is in this chasm between what it appears to be and what it is, where the real costs to our lives and health lay quietly and anonymously below the radar of our consumption.

When we ask ‘who made our clothes’ we come into contact with a suite of global supply chains that connect what we put on our skin each day to human-operated cut & sew facilities, finishers, knitters or weavers, yarn spinning, carding, washing, ginning, or fossil fuel extraction for resin chips (for synthetic fibers), and in the case of natural fibers—we end up back on the farm. When we begin to take note of the ‘who’ in all of these processes we unearth the story of their contribution and the reality of their task and the risks they endure. During this year’s Fashion Revolution Week and for the purposes of this write-up we start from the bottom up to ask ‘who grew our clothes, and how?’

For this exploration I am going to trace a few details related to the most ubiquitous natural fiber—cotton. The National Cotton Council states that in the United States the crop is grown in approximately 17 states and it covers 12 million acres of farmland. Three fourths of this cotton is used for our garments and 6.5 billion pounds of cottonseed enters the food system. We export our cotton to the tune of $7 billion and U.S. cotton accounts for 30% of the total world export market.

Above: Cotton loading module in California, credit – photogallery.nrcs.usda.gov

According the USDA, 94% of the cotton planted in the U.S. in 2015 was genetically engineered (GE). The vast majority of U.S. cotton is resistant to the use of key herbicides that contain glyphosate—these commercial herbicides are known as Round-up, PROMOX, and WeatherMAX.

These synthetic compounds are used widely to destroy other plant material in the field, while leaving the cotton present. According to the National Cotton Council, farmers spend $780 million per year on chemical inputs, and $170 million on farm labor. Chemicals now cost more than human labor.

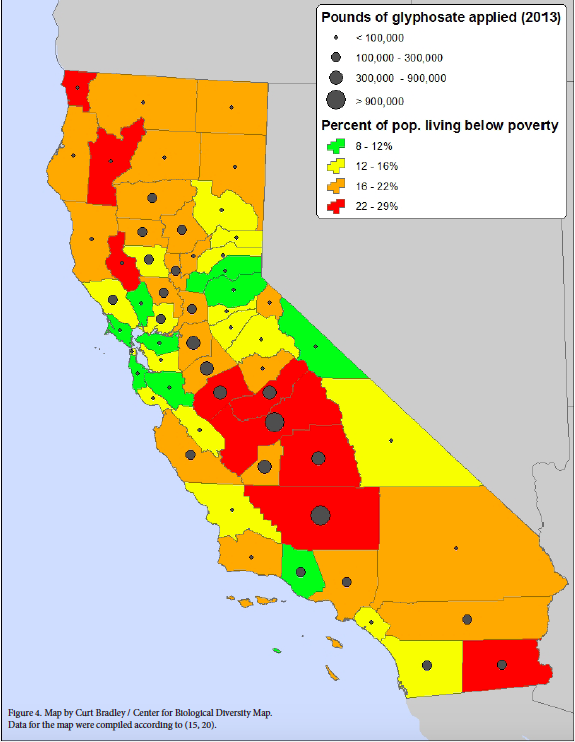

In regard to that labor and the reality of the working conditions in the GE cotton fields—a recent study from the Center for Biological Diversity from 2015, Lost in the Mist, illuminated that over half of the glyphosate used in California is sprayed in the state’s eight most impoverished counties, where 53% of the population is Hispanic or Latino (compared to 38% of the state as a whole). The southern part of California’s central valley is the heart of California cotton production, which includes the same counties identified in the study—Kern, Fresno, Tulare, Madera, Lake, Imperial, Merced and Del Norte. Farmworkers and land-managers applied over 10,370,147 pounds of glyphosate in our state alone in 2013, and 65% of that was used in these counties.

Above: Mapping glyphosate use in California alongside demographic data, in Lost in the Mist by Center for Biological Diversity

What are the costs of using this much glyphosate in our fiber and food system?

In a peer-reviewed study from the scientific journal Toxicology, it was shown that glyphosate disrupted human cells within 24 hours of exposure in sub-agricultural doses. DNA damage occurred with exposures as low as 5 ppm (parts per million), and endocrine disruption (effecting human hormone balance) occurred at as low as .5 ppm.

In another peer-reviewed report by the Annual Review of Physiology it was stated that new epidemiological studies have connected endocrine disruption to metabolic syndrome, obesity and type II diabetes. Residues of glyphosate on some feed are allowed at levels up to 400 ppm, and there are currently no laws regulating the concentration of glyphosate residues on our fibers. The skin’s ability to absorb environmental toxins is a more direct pathway to our blood supply than through that which we ingest (the digestive tract is designed to find and expel toxins more effectively than the dermis layers), however we often do not consider what we put on our body as detrimental to our health in the same way we consider the detrimental effects of the food supply.

Perhaps it is for that reason that the risks of growing and wearing Round-up Ready cotton remain a fairly unregulated and unstudied arena. However, toxicological reports agree that glyphosate—the main chemical used to sustain the genetically engineered cotton supply—must be considered carcinogenic, and exposures to this synthetic compound are occurring through multiple environmental pathways.

Having just spent time late last week at a strategy meeting on the True Cost of American Food, it is now becoming increasingly evident that the cost of the industrially produced food supply could very well be bankrupting us. We know that half of all Californians either have type II diabetes or are in a pre-diabetic condition, costing our state $27 billion in health care costs each year. Farther afield, on a global scale, obesity is costing us $2 trillion annually, equivalent to 20% of our global spending.

While I realize it is already a fairly herculean task to internalize the costs of our food system, I cannot forgo the opportunity to seek to persuade our food systems stakeholders to include the costs of our fiber system in their analysis. The same land that feeds us, is clothing us.

Above: the landscape that provided the materials and labor for Grow Your Jeans; photo by Paige Green.

The farm workers exposed to glyphosate are being subjected to this not only for food production, but also for fiber production. Our general population is being exposed to the compound via unregulated and yet to be measured ways via the fiber system, and it is clear that exposures are occurring through our food supply in concentrations known to create health risks. With such a low exposure threshold for endocrine disruption, it is clear we have a health crisis on our hands.

And then there is the task of turning the tide of mainstream consciousness, which includes the vast majority of wearers and eaters. In light of Fashion Revolution Week, and in light of all of the effort our local community is putting forward to illuminate the severe realities of this global industry—flash mobs, symposia, social media campaigns—it is still hard to say what forces will turn the tides of this industry. Perhaps the reality that our clothing is exposing us to endocrine disruptors, which are linked to obesity, metabolic disease, infertility, cancer, and diabetes?

It’s not just that those who are growing our clothes face these risks, it is all of us. While I’d like to think farm worker justice and welfare would be enough for the mainstream culture to change its consumption habits, I think that perhaps proliferating a more widespread understanding that the beauty we seek to create from fashion is being directly undermined by how we are producing it. I can imagine there are few who would be pleased to know that their clothing is harming their health.

You may ask, what are the options? With over 94% of our cotton being genetically engineered and reliant on the use of glyphosate-rich herbicides, what can we do?

Starting in our home community, there is a lot we can do. In our Fibershed of Northern California, we live within 150 miles of two cotton projects that are offering stellar options for the fashion industry.

Above: Sally Fox in her organic cotton fields in the Capay Valley, photos by Paige Green

To the north is Sally Fox, the first biodynamic certified color-grown cotton farmer in the United States, and a longtime organic practitioner and breeder who rotates her cotton with winter wheat, and co-plants with black-eyed peas, sunflowers and milo. Her fine flock of merino sheep grazes down her cotton stubble at the end of the season, cycling nutrients quickly for her next year’s crop.

To the south of us is the Sustainable Cotton Project, a project focused on providing a non-genetically engineered Pima and Acala Cotton at scale. Farther afield outside of our intimate region there is the West Texas Organic Cooperative, another scaled project that plants 10-19,000 acres per year. For all of these projects drought has intensified the pressures of what is already a thin margin crop.

To support these projects we recommend connecting with the farmer or co-op you find connects most deeply to your values or a strategic geography that you are committed to, and finding out who has been purchasing from these land-bases and where you can source finished garments and fabric.

As Fashion Revolution Week encourages each of us to ask ‘Who Made My Clothes?’ and to understand the fashion industry conditions which led to the lives lost and injured in the collapse of the Rana Plaza Complex in Bangladesh, we need to continue to seek that same transparency throughout the fashion and fiber system. Whether for the health and human rights of workers at every part of the supply chain down to the soil, or for our own personal health, we need to consider ‘who grew our clothes, and how?’