Syntropic Agriculture: Cacao, Costa Rica, Case Study

After organizing and attending our first syntropic farming workshop in 2019, our team at Porvenir Design knew that we were looking for just the right client to implement a larger scale system to learn more about these ideas. Finca Luna Nueva presented that opportunity as they were seeking to expand their existing cacao orchards and we had recently taken over full administration of their farm.

As part of this work we documented the transformation of the space during its first year and a half, from design and planning to implementation and feedback. This blog seeks to explain in detail exactly why and how we incorporated syntropic farming principles into the installation of a one hectare cacao orchard. It is also our chance to explore feedback, discuss what we would do differently in the future and hear from the larger syntropic farming community.

Special thanks to the Finca Luna Nueva farm crew: Carlos A., Jose, Eladio, David, Christopher, Frander, Nelson, Carlos R., and Walter for their diligence and patience.

Special thanks to Elena Valverde and Iva Alvarado for the photos and editing, Travis Wals for the video creation, and Alejandro Arturo for the graphics.

What is Syntropic Farming

Syntropic Farming is a process and principle based form of agriculture developed and propagated primarily in Brazil. Syntropic farming is a field within the larger domains of agroecology and agroforestry. Syntropic systems complement the food forest ideas within permaculture design by providing more specific design details, metrics, and arrangements that focus on precisely imitating the spatial and temporal relationships of the region’s native forest ecology. It has shown the ability to be scaled beyond many similar fields of agroecology. Syntropic agriculture provides a set of principles and tools for shifting from organic monocultures and input based agriculture towards a holistic focus on ecology. In the end it is a system that seeks to imitate the forest and results in a forest ecosystem.

This blog won’t attempt to define syntropic farming beyond this. The following links are key places to explore the topic.

Finca Luna Nueva and a New Ecology of Agriculture

Finca Luna Nueva (FLN) is a farm and eco-lodge located in the Costa Rican lowland Caribbean slopes, near the town of La Fortuna and the famed Arenal volcano. It is situated down river of the Bosque Eterno de Los Niños. FLN was one of the first certified organic and Demeter certified biodynamic farms in Central America, focused primarily on growing ginger and turmeric for export to the United States of America. The farm was successful in this endeavor until the soil fungal pathogen Fusarium sp became such an issue that total crop loss approached 80%. In the following years the farm resources shifted toward tourism activities as the lodge pivoted to remain financially viable and create diverse revenue streams. The Porvenir Design team was brought on board in 2018 to begin re-vitalizing the farm with a new perspective in agriculture.

Why Adopt Syntropic Farming in this Context?

As FLN watched their turmeric crops fail following conventional organic/biodynamic approaches, they realized a new approach was going to be required on the farm. Their agricultural exploration shifted towards a focus on ecology, in particular the microbial health of the farm as a whole. Our team brought the additional perspective of creating systems which imitate forest ecology. For us, syntropic farming nests within permaculture design as a more organized form of agroforestry, integrating existing concepts of alley cropping, intercropping, keyline design and layout, and tree crop based agriculture.

FLN has a long history of pushing the edge of agricultural norms, being early adopters of many now-commonplace techniques and crops. They have the resources to trial new systems, so this was our chance to apply our new knowledge of syntropic agriculture in an opportune setting.

The Context of the Site

-

Elevation: 350 m above sea level in the Tileran Cordillera of the Caribbean slope.

-

Climate: Wet tropics, 4000 mm of rain/year average, driest season from January through May.

-

Watershed: San Carlos river watershed

-

Slope: Gentle slope toward the SE, drop of 12 meters from high to low points.

-

Size of Orchard: 1.1 hectares

-

Existing Vegetation: Pioneer species, early secondary forest growth, five to eight years of rest from any previous agriculture depending on the location in the site.

-

Existing trees, approximately 100, after thinning of overstory for timber crops: 1/3 timber, 2/3 fruit trees primarily breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) and mamonchino (Nephelium lappaceum).

-

Neighbors: The orchard is within the original FLN farm, within a short walk to the lodge and other hotel infrastructure; the syntropic plot also borders 12 hectares of protected forest.

-

History: First cleared in 1997 for ginger planting. Management and practices included certified organic and biodynamic preparations/amendments, crop rotation, fallow period, tillage with oxen, cover crops, and earthworks with vetiver grass for erosion control.

Goals and Decision Making in the Syntropic Cacao Orchard

The stakeholders at FLN are highly involved as advocates within the regenerative agriculture movement, hence the system needed to demonstrate the principles of regenerative agriculture. Carbon sequestration in particular was an important goal in the design of the system.

In addition, we recognized the privilege and resources available at this particular project and wanted to leverage them to create an experimental system, as far from monoculture as possible. We anticipated it would be a complex system to manage, and we knew the farm crew, with decades of experience, would be able to do just this. We understood that this would be a very labor intensive system.

The more specific goals of the farm were to grow food for the lodge’s kitchen, while developing a few export grade cash crops (turmeric, cacao, ojoche) over all time scales. The system was designed to have yields within six months through 50 years. Much of the specific species selected to fill in the ecological niches were selected based on seed which we could source easily at quantity in our bioregion.

The COVID-19 pandemic struck after the initial set up of this system and forced our team to minimize labor intensive activities. Since the beginning of the pandemic we adjusted our goals to focus on maintenance of the most valuable crops, like cacao, while minimizing maintenance of short rotation crops.

Orchard Design

Row Design and Layout

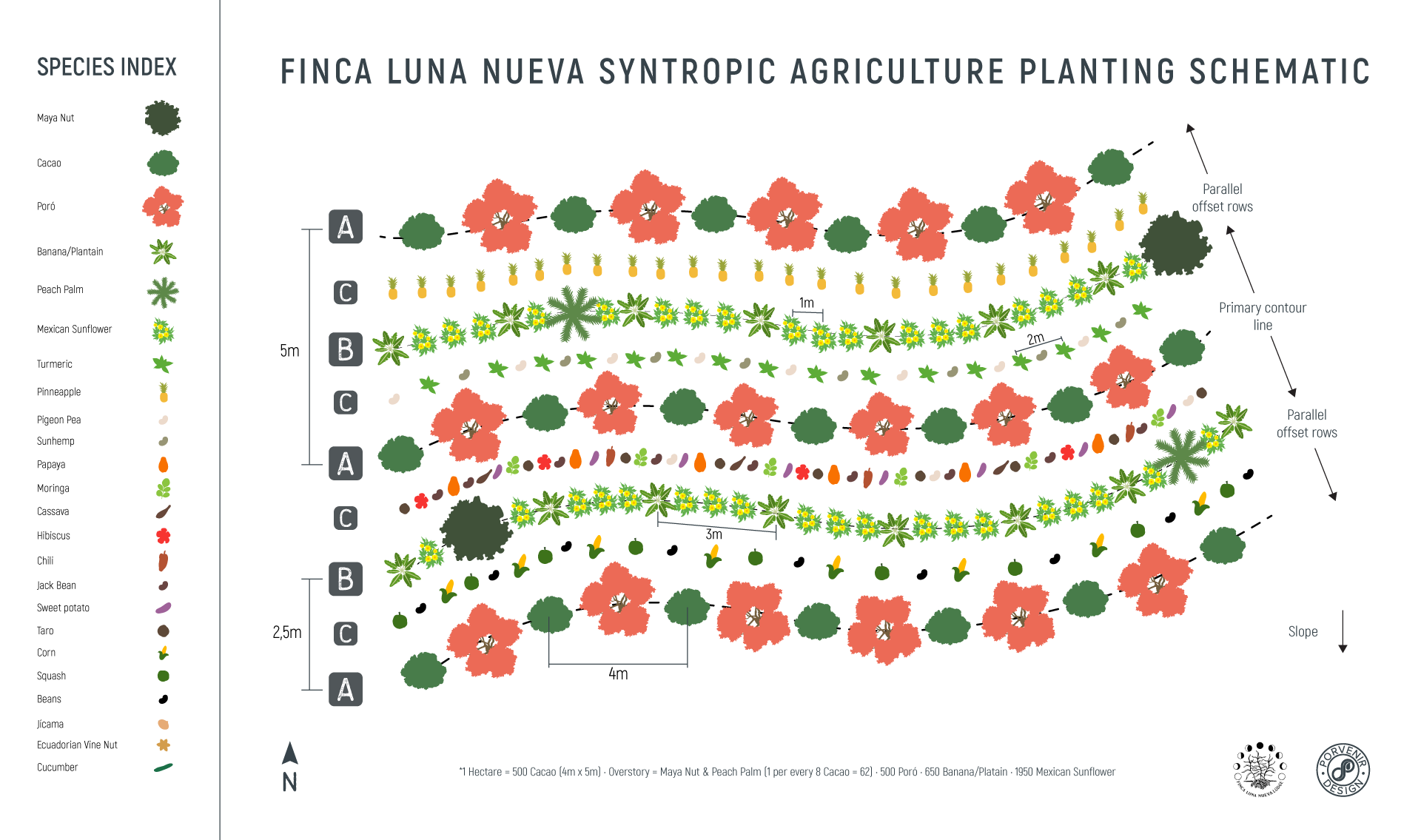

As can be seen in the below graphic, the system was designed primarily to accommodate the cacao crops. A rows, featuring cacao, are spaced at 5 meters distance, parallel and offset from an initial contour line near the top of the slope. In between these rows are B rows, and in between all A-B lines are C rows. The pattern looks as follows A-C-B-C-A-C-B-C-A-C.

In total there are 17 A rows, 17 B rows, and 34 C rows. The longest row is 129 meters, the shortest is 73 meters, and the average is approximately 110 meters long.

A row detail

-

Cacao (Theobroma cacao) planted every 4 meters

-

Poro (Erythrina sp.) posts planted every 4 meters between cacao

-

Pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) was planted between each cacao and poro post

-

In a few select rows Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia volubilis) was established on these poro posts

-

Jack Bean (Canavalia sp.) was seeded throughout the rows, especially around the cacao planting location

B row detail

-

Tithonia diversifolia was planted every meter

-

Musa sp were planted every 3 meters

-

Pejibaye (Bactris gasipaes) and Ojoche (Brosimum alicastrum) were planted every 18 meters, with the exceptions of locations with existing overstory trees .

C row detail:

-

Turmeric (Curcurma longa) was planted in mounds every 2 meters, 150 grams of turmeric per mound.

-

In a few select rows only pineapple were planted.

-

Between turmeric, depending on light conditions and seed material, the following crops were planted:

-

Papaya (Carica papaya)

-

Pigeon Pea

-

Rosa de Jamaica (Hibiscus sabdariffa)

-

Jack Bean

-

Sun hemp (Crotalaria sp.)

-

Squash (Cucurbita spp.)

-

Yuca (Manihot esculenta)

-

Chili Dulce (Capsicum annum)

-

Moringa (Moringa oleifera)

-

Beans (Phaseolus sp.)

-

Corn (Zea mays)

-

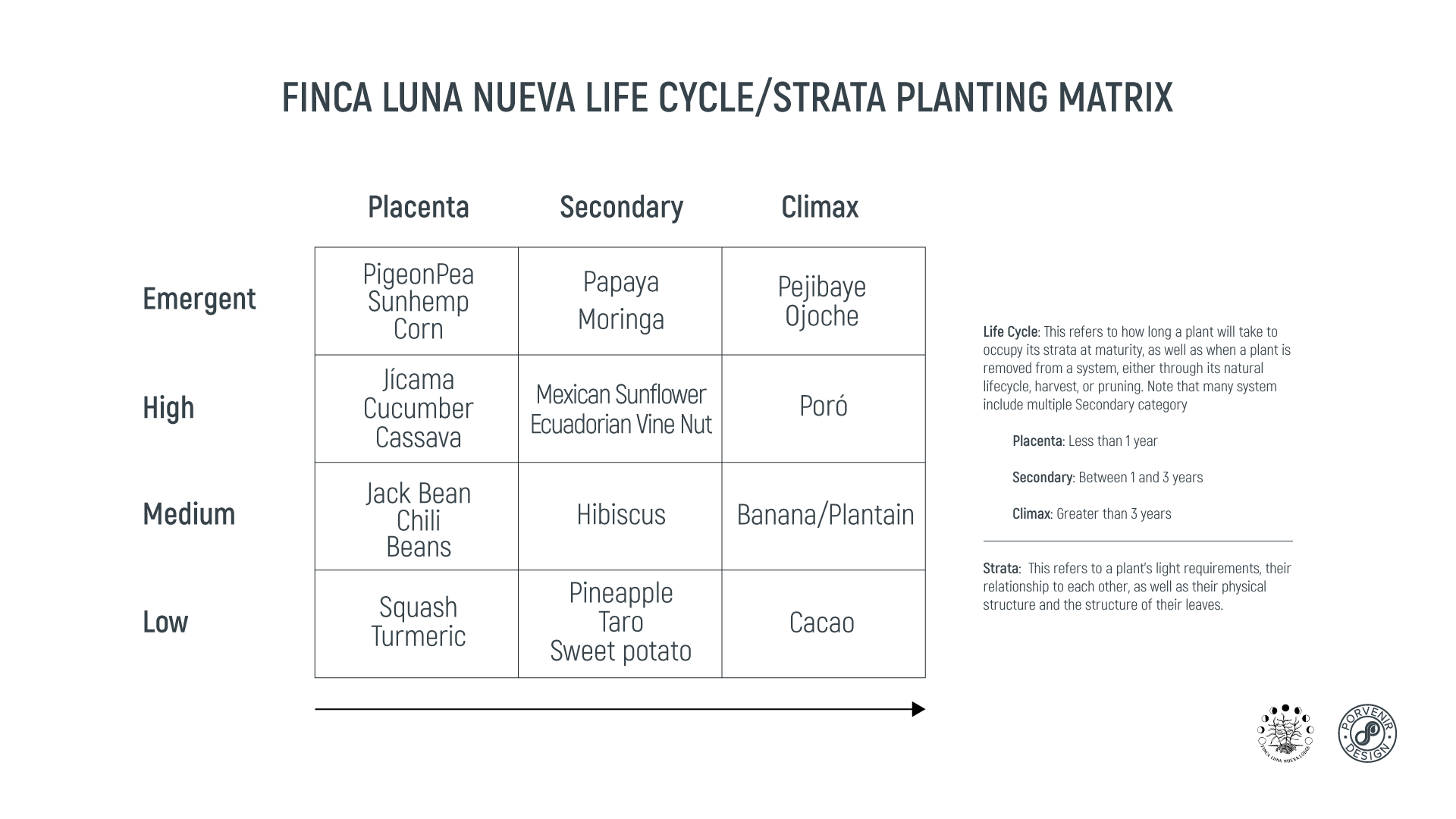

Strata and Life Cycle

The below chart demonstrates how and where each plant fits within their expected time and space niches, as the system evolves toward maturity. In syntropic systems, plants are used to prepare the conditions for the next life cycle of plants. Hence Placenta species will be pruned or harvested out of the system to make room for the Secondary group of plants to grow to maturity.

Plant and Other Materials

The following is an approximate list of the number of species put into the ground over the first year of this orchard:

-

500 cacao trees of the following varieties: Buffalo 1, UF 613, UF 653, ICS 95, R6

-

40 pejibaye palms

-

40 ojoche trees

-

450 kg of turmeric

-

2000 Tithonia cuttings

-

600 Musa sp seedlings

-

3000 gandul seedlings

-

20 kg of canavalia

-

2500 pineapple (Ananas comosus) starts

-

All other noted species were planted at relatively small numbers by comparison.

Compost was applied to the base of each fruit tree and to the turmeric mounds. In total 2500 kgs of compost were applied

Mountain Microorganisms (MM) and other foliar sprays such as fish emulsion (Pescagro) have been applied to the fruit trees and turmeric periodically.

Two strands of woven electric wire were used to fence the entire site to prevent animal predation of crops, particularly that of wild pigs.

Implementation and Management Process

Our first step began with clearing the land. This process took approximately two months, and we laid out the orchard as it was cleared. We removed approximately 5000 cubic inches of milled timber with an oxen team in this process.

The first A row was selected from an existing contour line near the top of the slope. All lines were pulled parallel from this line. This allowed us to maintain equidistant spacing between lines but still approximate the natural topography of the slope.

A small part of the orchard was laid out and planted during our Permaculture Design Course, the rest of the work was accomplished by the FLN farm crew, six full time workers.

Plantings were done first to delineate the A and B Rows with Tithonia, Musa, and Poro in particular. The approximate calendar of installation looked as followed:

-

October-November 2019: Clearing and lay out of lines

-

November -December 2019: Primary planting to delineate lines

-

December- February 2020: Planting of long term overstory trees/palms, cover crops, and most shorter rotation crops

-

March – April 2020: Harvest of squash, beans, corn, and cover crop seeds

-

May 2020: Heavy pruning, planting of turmeric crop

-

June 2020: Planting of cacao trees

-

August 2020: Heavy pruning

-

December 2020: Cacao maintenance

-

February 2021: Heavy pruning and cacao formation pruning

This first heavy pruning occurred in May 2020 prior to the planting of the turmeric crop. This primarily involved pruning or removing Tithonia, Pigeon Pea, and Jack Bean to create more light. A second pruning occurred in August to open up additional light for the turmeric and cacao trees. A third heavy pruning occurred in February 2021. Ideally all planting would have occurred at the same time but was limited due to sourcing and logistical challenges.

Foliar sprays are applied every three months to at least the cacao crop. Specific pest control sprays are applied as the farm crew sees fit. It is important to understand that in this context, the farm crew has years of experience working within organic systems and has an understanding of remedies for in field issues such as insect pressure, bacterial/fungal influence, and more.

Harvest

While the pandemic significantly reduced both the lodge’s demand for food and the farm crew’s hours, we have experienced significant harvests of existing breadfruit and mamon chino trees, bananas, and plantains. We harvested and continue harvesting smaller quantities of chili, pina, corn, beans, and yucca. The turmeric harvest will occur in April 2021.

Feedback and Conclusion

Our team continues to take in a number of lessons from this installation and management. The following are from our notes on what we learned and would have done differently.

-

Parallel Offset versus Triangulation: When laying out the initial cacao tree planting holes, we expected to triangulate the trees from each other while maintaining the equidistant planting lines. After much head scratching, we realized this is impossible on a terrain whose topography varies even slightly. We could only do one or the other. As usual, it was a challenge to take something from theory and put it into practice on a larger scale.

-

Pest Control: Our workers stated very clearly that tuber, grains, and pulses would be easy food for nearby wildlife. We wanted to see if a more diverse system, with more regular human presence would deter this, but quickly found out that wild pigs don’t care about those ideas. We adjusted rapidly and placed an electric fence around the entire hectare. An alternative decision would have been to simply not grow these types of short rotation crops. There is a good argument to be made that the cost of the fence and its maintenance is not worth the benefit of mixing our long term perennials, which don’t need protection, with these short rotation crops.

-

Access: In hindsight we would have adjusted the line layout slightly. Around the halfway point of the slope we would have liked to add a wider access path and used this to find a new contour line and run the lower lines parallel and offset to this. We considered this at the start but in order to simplify the installation process, decided against it.

-

Seeding Logistics: We used a mix of direct seeding, bare rooting plants from in ground planters and establishing plants in bags prior to planting. There are distinct pros and cons to each of these. In general we feel that the more one can direct seed the better, but this requires a higher level of skill from the farm crew. We are continually working with our farm crew to determine what they believe are the most efficient methods.

-

Simplification: During our workshop in 2019, we were astounded by the complexity and number of plant species and interactions that were recommended by our instructors. We sought to replicate this, despite some hesitation, by incorporating 23 different species into this system. Many of these crops did not thrive because it was simply too challenging, in our context, to manage this complexity. Some of this was based on having too few plants, some based on COVID labor shortages, some on poor crop selection, and so forth. In a more recent 3000 sq meter vanilla orchard we simplified our syntropic system to around 10 species.

-

Limitations of Organic Certification: It has become clear to us in this process, and with another installation at a different site, that conventional organic certification does not match well with highly diverse systems such as this. We felt severely limited in the soil amendments we could use and the complications of documenting all the sourcing becomes a part time job for someone. Organic certification is clearly designed for input-based agriculture and not process-based agriculture.

-

Pruning, Light and Biomass Management: We found ourselves needing to heavily prune certain biomass species to open up more sunlight for the turmeric and cacao. Although many crops can adjust to shade, they really need lots of sun to start growing well. This management, the details of pruning, has been the most challenging piece to communicate to our farm crew, as we learn with them. In addition figuring out exactly where to place biomass on the ground has been a full conversation, as the biomass both helps with weed suppression but also makes clearing around young trees more challenging. These are the details which we will be playing with for years to come.

In summary, we are excited to keep learning about syntropic systems in the future and hope that this project can be a source of inspiration and learning for anyone else interesting in this realm. Come and visit the farm!