Regenerate—to give fresh life or vigor to; to reorganize; to recreate the moral nature; to cause to be born again. (New Webster’s Dictionary, 1997)

When a reporter asked him [Mahatma Gandhi] what he thought of Western civilization, he famously replied: “I think it would be a good idea.”

A growing corps of organic, climate, environmental, social justice and peace activists are promoting a new world-changing paradigm that can potentially save us from global catastrophe. The name of this new paradigm and movement is regenerative agriculture, or more precisely regenerative food, farming and land use.

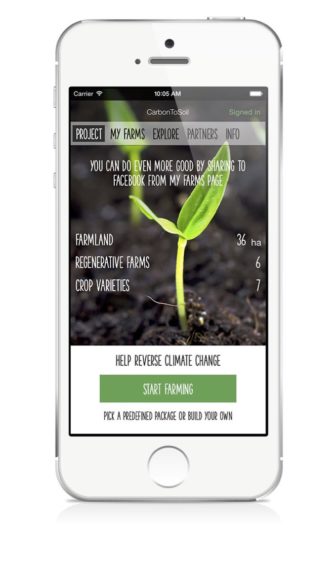

Regenerative agriculture and land use incorporates the traditional and indigenous best practices of organic farming, animal husbandry and environmental conservation. Regeneration puts a central focus on improving soil health and fertility (recarbonizing the soil), increasing biodiversity, and qualitatively enhancing forest health, animal welfare, food nutrition and rural (especially small farmer) prosperity.

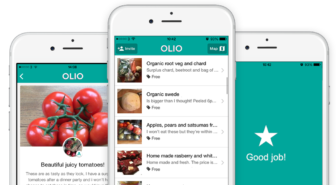

The basic menu for a Regeneration Revolution is to unite the world’s 3 billion rural farmers, ranchers and herders with several billion health, environmental and justice-minded consumers to overturn “business as usual” and embark on a global campaign of cooperation, solidarity and regeneration.

According to food activist Vandana Shiva, “Regenerative agriculture provides answers to the soil crisis, the food crisis, the health crisis, the climate crisis, and the crisis of democracy.”

So how can regenerative agriculture do all these things: increase soil fertility; maximize crop yields; draw down enough excess carbon from the atmosphere and sequester it in the soils, plants and trees to re-stabilize the climate and restore normal rainfall; increase soil water retention; make food more nutritious; reduce rural poverty; and begin to pacify the world’s hotspots of violence?

First, let’s look at what Michael Pollan, the U.S.’s most influential writer on food and farming, has to say about the miraculous regenerative power of Mother Nature and enhanced photosynthesis:

Consider what happens when the sun shines on a grass plant rooted in the earth. Using that light as a catalyst, the plant takes atmospheric CO2, splits off and releases the oxygen, and synthesizes liquid carbon–sugars, basically. Some of these sugars go to feed and build the aerial portions of the plant we can see, but a large percentage of this liquid carbon—somewhere between 20 and 40 percent—travels underground, leaking out of the roots and into the soil. The roots are feeding these sugars to the soil microbes—the bacteria and fungi that inhabit the rhizosphere—in exchange for which those microbes provide various services to the plant… Now, what had been atmospheric carbon (a problem) has become soil carbon, a solution—and not just to a single problem, but to a great many problems.

Besides taking large amounts of carbon out of the air—tons of it per acre when grasslands [or cropland] are properly managed… that process at the same time adds to the land’s fertility and its capacity to hold water. Which means more and better food for us…

This process of returning atmospheric carbon to the soil works even better when ruminants are added to the mix. Every time a calf or lamb shears a blade of grass, that plant, seeking to rebalance its “root-shoot ratio,” sheds some of its roots. These are then eaten by the worms, nematodes, and microbes—digested by the soil, in effect, and so added to its bank of carbon. This is how soil is created: from the bottom up… For thousands of years we grew food by depleting soil carbon and, in the last hundred or so, the carbon in fossil fuel as well. But now we know how to grow even more food while at the same time returning carbon and fertility and water to the soil.

A 2015 article in the Guardian summarizes some of the most important practices of Regenerative Agriculture:

Regenerative agriculture comprises an array of techniques that rebuild soil and, in the process, sequester carbon. Typically, it uses cover crops and perennials so that bare soil is never exposed, and grazes animals in ways that mimic animals in nature. It also offers ecological benefits far beyond carbon storage: it stops soil erosion, re-mineralizes soil, protects the purity of groundwater and reduces damaging pesticide and fertilizer runoff.”

If you want to understand the basic science and biology of how regenerative agriculture can draw down enough excess carbon from the atmosphere over the next 25 years and store it in our soils and forests (in combination with a 100-percent reduction in fossil fuel emissions) to not only mitigate, but actually reverse global warming, read this article by one of North America’s leading organic farmers, Jack Kittridge.

If you want a general overview of news and articles on regenerative food, farming and land use, you can follow the newsfeed “Cook Organic Not the Planet” by the Organic Consumers Association (OCA), and/or sign up for OCA’s weekly online newsletter (you can subscribe online, or text “Bytes” to 97779.)

You can also visit the Regeneration International website, where you’ll find this list of books on regenerative agriculture.

Solving the soil, health, environmental and climate crises

Without going into extensive detail here (you can read the references above), we need to connect the dots between our soil, public health, environment and climate crisis. As the widely-read Mercola newsletter puts it:

Virtually every growing environmental and health problem can be traced back to modern food production. This includes but is not limited to:

- Food insecurity and malnutrition amid mounting food waste

- Rising obesity and chronic disease rates despite growing health care outlays

- Diminishing fresh water supplies

- Toxic agricultural chemicals polluting air, soil and waterways, thereby threatening the entire food chain from top to bottom

- Disruption of normal climate and rainfall patterns

Connecting the dots between climate and food

We can’t really solve the climate crisis (and the related soil, environmental, and public health crisis) without simultaneously solving the food and farming crisis. We need to stop putting greenhouse gas pollution into the atmosphere (by moving to 100-percent renewable energy), but we also need to move away from chemical-intensive, energy-intensive food, factory farming and land use, as soon as possible.

Regenerative food and farming has the potential to draw down a critical mass of carbon (200-250 billion tons) from the atmosphere over the next 25 years and store it in our soils and living plants, where it will increase soil fertility, food production and food quality (nutritional density), while re-stabilizing the climate.

The heavy use of pesticides, GMOs, chemical fertilizers and factory-farming by 50 million industrial farmers (mainly in the Global North) is not just poisoning our health and engendering a global epidemic of chronic disease and malnutrition. It’s also destroying our soil, wetlands’ and forests’ natural ability to sequester excess atmospheric carbon into the earth.

The good news is that solar and wind power, and energy conservation are now cheaper than fossil fuels. And most people are starting to understand that organic, grass-fed and freshly-prepared foods are safer and more nutritious than chemical and GMO foods.

The food movement and climate movements must break through our single-issue silos and start to work together. Either we stop Big Coal, Big Oil, fracking, and the mega-pipelines, or climate change will soon morph into climate catastrophe, making it impossible to grow enough food to feed the planet. Every food activist needs to become a climate activist.

On the other hand, every climate activist needs to become a food activist. Our current system of industrial food, farming and land use, now degenerating 75 percent of all global farmland, is “mining” and decarbonizing the soil, destroying our forests, and releasing 44-57 percent of all climate-destabilizing greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and black soot) into our already supersaturated atmosphere, while at the same time undermining our health with commoditized, overly processed food.

Solving the crisis of rural poverty, democracy and endless war

Out-of-touch and out-of-control governments of the world now take our tax money and spend $500 billion dollars a year mainly subsidizing 50 million industrial farmers to do the wrong thing. These farmers routinely over-till, over-graze (or under-graze), monocrop, and pollute the soil and the environment with chemicals and GMOs to produce cheap commodities (corn, soy, wheat, rice, cotton) and cash crops, low-grade processed food and factory-farmed meat and animal products. Meanwhile 700 million small family farms and herders, comprising the 3 billion people who produce 70 percent of the world’s food on just 25 percent of the world’s acreage, struggle to make ends meet.

If governments can be convinced or forced by the power of the global grassroots to reduce and eventually cut off these $500 billion in annual subsidies to industrial agriculture and Big Food, and instead encourage and reward family farmers and ranchers who improve soil health, biodiversity, animal health and food quality, we can simultaneously reduce global poverty, improve public health, and restore climate stability.

As even the Pentagon now admits, climate change, land degradation (erosion and desertification), and rural poverty are now primary driving forces of sectarian strife and war (and massive waves of refugees) in places like Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya and Somalia. U.S. military intervention in these regions, under the guise of “regime change” or democratization, has only made things worse. This is why every peace activist needs to become a climate and food activist and vice-versa.

Similarly corrupt, out-of-control governments continue to subsidize fossil fuels to the tune of $5.3 trillion dollars a year, while spending more than $3 trillion dollars annually on weapons, mainly to prop up our global fossil fuel system and overseas empires. If the global grassroots can reach out to one another, bypassing our corrupt governments, and break down the geographic, linguistic and cultural walls that separate us, we can launch a global Regeneration Revolution—on the scale of the global campaign in World War II against the Nazis.

One thing we the grassroots share in all of the 200 nations of the world is this: We are sick and tired of corrupt governments and out-of-control corporations degenerating our lives and threatening our future. The Russian people are not our enemies, nor the Chinese, nor the Iranians. The hour is late. The crisis is dire. But we still have time to regenerate our soils, climate, health, economy, foreign policy, and democracy. We still have time to turn things around.

The global Regeneration Movement we need will likely take several decades to reach critical mass and effectiveness. In spreading the Regeneration message, and building this new Movement at the global grassroots, we must take into account the fact that most regions, nations and people (and in fact many people who are still ignorant of the facts or climate change deniers) will respond more quickly or positively to different aspects or dimensions of our message (i.e. providing jobs; reducing rural and urban poverty and inequality, restoring soil fertility, saving the ocean and marine life, preserving forests, improving nutrition and public health, eliminating hunger and malnutrition, saving biodiversity, restoring animal health and food quality, preserving water, safeguarding Mother Nature or God’s Creation, creating a foundation for peace, democracy, and reconciliation, etc.) rather than to the central life or death message: reversing global warming.

What is important is not that everyone, everywhere immediately agrees 100 percent on all of the specifics of regenerative food, farming and land use—for this is not practical—but rather that we build upon our shared concerns in each community, region, nation and continent. Through a diversity of messages, frames and campaigns, through connecting the dots between all the burning issues, we will find the strength, numbers, courage and compassion to build the largest grassroots coalition in history—to safeguard our common home, our survival, and the survival of the future generations.

Ronnie Cummins is international director of the Organic Consumers Association and a founding member of Regeneration International.