Healthy Soils are the Basis for Healthy Food Production

[ Italiano ]

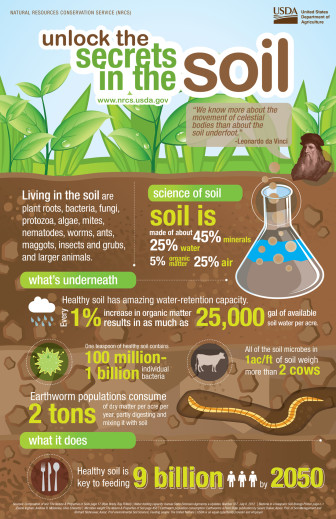

Healthy soils are the basis for healthy food production. The most widely recognized function of soil is its support for food production. It is the foundation for agriculture and the medium in which nearly all food-producing plants grow. In fact, it is estimated that 95% of our food is directly or indirectly produced on our soils. Healthy soils supply the essential nutrients, water, oxygen and root support that our food-producing plants need to grow and flourish. Soils also serve as a buffer to protect delicate plant roots from drastic fluctuations in temperature.

What is a Healthy Soil?

Soil health has been defined as the capacity of soil to function as a living system. Healthy soils maintain a diverse community of soil organisms that help to control plant disease, insect and weed pests, form beneficial symbiotic associations with plant roots, recycle essential plant nutrients, improve soil structure with positive effects for soil water and nutrient holding capacity, and ultimately improve crop production. A healthy soil also contributes to mitigating climate change by maintaining or increasing its carbon content.