The chicks have arrived! A 6 a.m. phone call from the Northfield, Minnesota, post office alerted Eric Foster and others at the Main Street Project to the arrival of the first training flock of 2018. A new cohort of aspiring Latino farmers from the south-central region of Minnesota were about to start their poultry-centered regenerative agriculture training.

Their mission? To become part of a southeastern Minnesota cluster of farms designed to change the way poultry is produced in Minnesota and beyond, by joining dozens of other families in the region who have received similar training from Northfield-based Main Street Project.

Why Do We Need to Change How Poultry Is Produced?

The current poultry-production system has failed ecologically, economically and socially. It has caused ecological destruction, displacement of rural people and destroyed ancient resilient and healthy food security systems for communities worldwide. It has loaded animal production with pharmaceuticals, then hidden this information from consumers. The system has also built a massive global exploitative infrastructure that cheats farmers and consumers.

Today’s system never intended to deliver solutions. It was designed and structured to be extractive, degenerative and profit-driven. Through massive, well-funded campaigns, today’s poultry producers create the illusion that they can deliver large amounts of healthy food at very low prices. But the true cost of industrial food is hidden behind the convoluted systems the industry has created.

Some of those costs are obvious, yet we have no legal recourse to demand payment. Who pays for the ever-expanding list of food-related diseases? Or water contamination? Who pays the social cost of pushing food and agriculture workers into poverty?

The Real Cost of Cheap Food

Consumers pay the real cost of our food through a vast array of channels that have become untraceable, from our taxes that primarily subsidize a handful of large corporations through the Farm Bill—a cyclical federal agricultural subsidy program—to the public subsidies, volunteers and local taxes that go to clean up rivers, lakes and even oceans polluted in the name of feeding the world.

Some of this cost materializes when residents of cities where agriculture runoff has now impaired drinking water are taxed to pay for the cleanup of toxic levels of nitrates and other agricultural chemicals.

We need to change the system: It is not in its DNA to change itself. We, the billions of small farmers, consumers, scientists and students, need to reclaim control of our food production and redeploy under a regenerative design. In my book, “In the Shadow of Green Man,” I describe the life experiences and pathways that led me to this work and to this point in my life.

In this autobiographical book, I lay the foundation for why we need to fight for large-scale change, and why we should always look with distrust at anyone or any structure that seeks to degenerate the foundation of our well-being through our food, the most sacred foundation of nutrition, health and well-being.

Before publishing “In the Shadow of Green Man,” I did an interview with Dr. Mercola, where I laid out the principles for how we are redesigning a new poultry system. Our design process takes us back to the source of how nature provides a magnificent blueprint for energy transformation processes that deliver food out of air and soil.

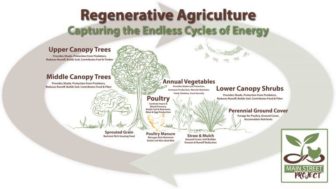

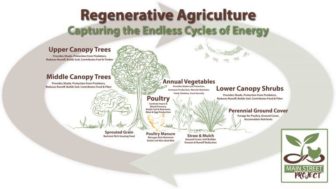

Defining a Regenerative System

A regenerative system is one that can continually recirculate the natural energy from the soil and air to deliver not only a healthy environment, but also healthy foods, fiber and other vital outcomes of a regenerating landscape. Livestock on the landscape is critical to this process. And when it comes to livestock, chicken reigns supreme.

Poultry production offers the shortest economic cycle and lowest up-front investment cost. It is the only livestock that is accepted culturally in every region of the world. It is a healthy protein source and is easily scalable. If we design a system according to the chicken’s natural jungle environment, poultry can also serve as the foundation for a massive new agroecological and agroforestry model, capable of reforesting and restoring large amounts of conventionally farmed and degenerated landscapes.

We looked at the chicken’s original natural environmental blueprint in the jungles of southeast Asia and followed it across the world. The ancestors of the modern chicken (Gallus gallus, aka red jungle fowl) have adapted to most ecological condition. Like most other animals, chickens were never meant to be confined indoors—and they don’t have to be.

The only reason to confine animals is for ownership and control and to maximize profits. The industry did this, whether intentionally or not, at the expense of the welfare of the animals, the health of consumers, the environment, farmers and workers.

As a child, I watched a big fight roar around us as the Guatemalan civil war carried on. That was the Guatemalans’ way of attempting to remove from power the oligarchs and their army that ruled and controlled the land, under a system based on extraction, exploitation and abuse. As a child within this environment, my stories were defined by poverty and hunger and the need for more food. My understanding of its value and our right to it grew out of that environment, as did my desire to work for this inalienable right.

Today, as I hear Native American elders talk about food sovereignty as one challenge to their freedom, it confirms my decision to spend the rest of my life dedicated to this fight. One freedom that should not be compromised is the freedom to collectively own and control our food and agriculture system. Today we have a new plan, and as you may have guessed, it starts with a chicken-led revolution.

Starting From the Bottom Up

At Main Street Project, the focus on Latino families as a strategic starting point for launching regenerative poultry and grain systems was not coincidental. It became key to our strategy for movement building and market development. It was important to start with the natural geo-evolutionary blueprint of the chicken. But it was equally important that the starting point take into consideration the natural ability of immigrant farmers, especially Latinos, as a social impact foundation of our theory of change.

Each production unit that now serves as the foundation of this system was designed from the perspective of an aspiring immigrant or low-income farmer. We believed that by taking this approach, we would make the system structurally compatible with any farmer in the world and especially in the U.S.

The key was to design the production unit as simple and as complete as possible so that any farmer could start, grow and scale production systemically under a controlled and managed process. To analyze existing ideas, we developed a set of core principles, criteria, indicators and verifiers that guided the discovery of what others were doing, while also guiding our own design process.

Establishing the Foundation of the Poultry-Centered Regenerative Design

To design, you need a standard. But to get to a standard, you first need to know the departing and destination points. From the beginning, in 2007, we were clear on two things. First, we were going to design from the perspective of nature to the extent that we could decipher it. Second, we wanted to design with people in mind: consumers, farmers and farmworkers as the primary beneficiaries of the system.

If we did these two things right, we would get the farm economics right. Contrary to what some believe, we don’t get regenerative farming right by getting the economics right. As Charles Walters of Acres U.S.A. said in 1970, “To be economical agriculture must be ecological.”

Following this logic, we used our system-level principles, criteria, indicators and verifiers to organize an ecological, economic and social high impact design framework. The production unit details result from this process and give the farmer a concrete project-level engagement platform.

We base the farm-level strategy on the number of production units a farmer wants to deploy on his farm. A region of farm clusters within a state serves as the foundation for building support infrastructure such as processing facilities, value-added products and distribution. Clusters linked and structured within a larger multistate regional strategy anchor the building of industry-level infrastructure such as trade, commerce, financing and governance.

We don’t create the process by which one organizes an industry; we simply weave our system into existing and known processes, with the proper adaptations, to lead to our own predefined destination—a regenerative agriculture and food industry. Critical to this process is the fact that a farm is not a system.

A farm is a project that if properly designed and aligned, can become part of a system design. For this to happen, the farm must meet a set of standardized practices, procedures, accountability, scientific protocols and measurable outcomes. It must consistently produce a predictable scalable output (food or raw material product) no matter where it is located. Then, production can be aggregated with other producers and form the basis for a system design.

The Poultry-Centered Regenerative System Standard

Our standard fully integrates the environment for the chicken, the social foundation for the system deployment and the economics of farming and food industry management. Starting with nature’s blueprint, we weave the economic and social together to build a framework that delivers an integrated standard.

By design, our poultry production model breaks out of the traditional mold of the fossil-based industrial revolution that delivered us the current system. We have created a blueprint for a broad and synchronized model that can integrate fully with the new “internet of things” revolution.

Similarly, global trends are rapidly coming to life as a “third industrial revolution” emerges out of Europe and China. What this does is link the ecosystems benefits while integrating tracking and management technology that can aggregate ecological, social and economic data at virtually no aggregated costs to the system. This delivers a fully transparent system that consumers, farmers and everyone else can access.

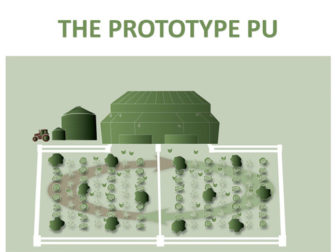

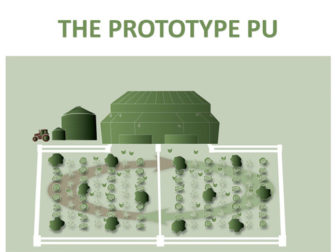

The Production Unit

A production unit (PU) represents a snapshot of the system at a point where the farmer can make basic economic and social sense of what he/she is about to deploy. Ecologically, the PU allows the farmer to calculate the inflow of energy into the production process in the form of feed, grain and other inputs, and the amount of outflow of energy in the form of eggs, meat, nuts and fruits.

This forms the foundation for business planning at all levels. The PU comprises a shelter, two fenced-in paddocks, perennial and annual crops and other common poultry-related infrastructure to manage feed and watering. The paddocks are designed to vertically integrate as much production as possible while providing a multitude of other benefits that will be outlined later.

The PU is critical when calculating ecological impact. Anything that goes through the production process can be measured across the board no matter if a PU is in Minnesota, Mexico or Guatemala—wherever operations are already underway and the PU design has undergone full adaptation to those specific ecological, economic and social conditions. The cornerstones of the PU are the:

- Shelter: primarily protects the chickens during the night and during inclement weather

- Paddocks: provide ranging area

- Protective perennial and annual canopy11: directly defines the distance the chickens roam from their shelter and creates the foundation for management of chicken behavior. This includes stress management, ranging distance and temperature to name a few

- Sprouting systems: probably the most important of all, given that the cost of raising a pound of meat or a dozen eggs is significant (upward of 70 percent of the total cost)

How Cheap Grain Has Influenced America’s Food System

To understand this last point properly, it is important to clarify the role of cheap grain in the takeover of America’s food system. Taxpayer-subsidized grain production—mostly corn and soybeans—keep feed grain prices low for conventional farms.

The “external costs” are passed on to future generations in the form of degenerated landscapes, polluted groundwater systems and health issues related to the use of toxic chemicals. Taxpayers foot the bill under a system that transfers all the costs to society, and all the benefits to industry.

As for farmers, today’s farm bill subsidies12 don’t really help farmers. Instead, they represent the systematically structured flow of public funding that primarily enriches agribusiness disguised as a public benefit. Farmers across the country are left holding the risky part of the farm industry. According to Christopher Leonard, author of “The Meat Racket,”13 only about 5 cents of the price a consumer pays at the store for a pound of chicken ends up reaching the farmer.

The rest stays in the industrial chain. From that meager operating income, the farmer has to pay for the full cost of production such as their own salaries, farm labor, the interest to the bank, and building improvements and fixes—some of them mandated by the industry. This system effectively creates a firewall so no one can accuse a corporation of getting direct payments from the government.

Shifting the process by how grain is turned into eggs or meat, how farmers, farm and food-chain workers benefit from the system is critical to redesigning any sector of the food industry. Along with proper engineering and careful integration of natural efficiencies, we can deliver a blueprint for a different way of producing poultry that can be standardized and replicated, and that is fully adaptable to the regenerative nature of different ecologies, cultures and economic landscapes.

The Importance of Protective Canopy When Raising Free-Range Chickens

Each PU we design, and the standard that goes with it, has been carefully structured to deliver ecological, economic and social returns on investment. It is from that position of strength, transparency and integrity that we plan to launch a “chicken revolution” as our Guatemalan counterparts have renamed this idea.

Chickens are extremely responsive to and aware of their environment. As we fine-tuned the production unit’s management process, we learned that the canopy was not only essential for them to relax and roam most of the day outside, but also to protect them from aerial predators. The canopy also cools the soil by blocking the sun, which increases the relative humidity.

When all of these conditions are added up, the result is a perfect environment for large-scale natural sprouting of grain exactly where the chickens want it. Not only did we find ways to scale that source of food, but the chickens also supplement their diet more significantly by taking in more biomass, nutrients and water volume from sprouts, thus reducing the extra feed that they need when free-ranging.

By eliminating the need for industrial GMO grain production, this system not only reduces pollution, but actually mitigates it. The trees’ uptake of nutrients from the soil reduces and eventually eliminates pollution of water, soil and air. Trees also add value by helping to reverse climate change. The chemicals they emit into the atmosphere help stabilize rain patterns. In addition, trees sequester carbon from the atmosphere and produce oxygen, fiber, fruits, nuts and many other foods and ecological benefits.

A Return to Slow-Growth Poultry Breeds

For meat bird PUs, we selected slow-growth breeds that range well rather than the genetically degenerated industrial chickens. The industrial meat bird has lost its ability to properly range and live a healthy natural life. These birds are bred for confinement. Their body proportions and the way their organs develop make them unfit for free-ranging systems.

They have an incredible capacity to gain weight and with it, the need for a sedentary confined life. All of these characteristics are counter to the foundational principles and concept of regenerative agriculture.

In our system, the maximum stock density per PU for broilers is 2 square feet per bird. No more than 1,500 birds are permitted in each building. In northern cold climates, up to three slow-growth flocks (harvested at 70 days on average) can be raised delivering a total of around 4,500 birds per PU. For the Midwest ecology (different outdoor spacing and density is required for different ecologies), each bird must be allowed at least 42 square feet of ranging space or a total of 21 square feet per paddock.

In general, the unit must be laid out so that the farther corners are not further than 200 feet from the shelter’s exit doors. Ranging paddocks with perimeter fences farther than that will require more weed control, and birds will exceed the expected use of the areas closer to the shelter. Feed is not allowed indoors except during their four-week brooding period and during inclement weather. The rest of the time, feeders are fanned out farther and farther from the building to encourage ranging.

For egg layers, the PU consists of 3 acres of ranging area divided into two paddocks. Shelter requirement is set at a minimum of 1.8 square feet per bird. Maximum flock size is 3,000 hens. Shelter must be equipped with perches and other related infrastructure that is spelled out in the production manual provided to farmers after they complete their training.

A Farmer’s Cluster

With the PU defined, farms can be designed and other parts of the system integrated. First comes poultry processing or egg processing, then value-added processing and then distribution. In most of the country, there are no small custom processors that can handle more than a few thousand chickens a day.

Most of the processing infrastructure in the country is owned and controlled by the industrial system and unavailable to serve alternative systems. The need to plan clusters of farmers instead of single-farm operations emanates from these challenges.

Compared with a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO), one of our clusters represents a small number of animals. Unfortunately, the weakest link defines the strength of the whole chain, and so it is with food chain design. In the case of our regenerative poultry and grain system, the weakest link is processing.

Under the current system, it is impossible to dream of setting up a large-scale poultry processing facility. However, it is possible to design a starting point that allows for a group to focus their energy on this area for each farm cluster.

Taking the System to Scale

As we approach the 2018 growing season, we sit on a significant number of accomplishments. We moved from prototyping and proof-of-concept to the launch of the Main Street Project’s central farm14 out of Northfield. This farm will train and develop the capacity of a new generation of farmers throughout the Midwest with a focus on training the first farmer cluster in Southeast Minnesota.

Another important achievement we are ushering in this year is the launch of Regeneration Farms,15 the first commercial farm utilizing the system.

But we still face some challenges when it comes to scaling up the system. To scale means more than to deploy a regional cluster of farmers. We can’t just assume what scale in the poultry industry is—it has to be studied, measured and defined. The magnitude of each little detail in the industrial poultry system is simply breathtaking, from how many tens of thousands of birds are confined in a building to the millions of egg layers that go into a single caged egg production facility.

We studied this model and came to the realization that in order to scale up, we also need to organize at scale. Back in 2015, I became a founding member of Regeneration International,16 a global network of scientists, farmers, business leaders and grassroots organizations that also saw the need to organize at scale with an industry redesign at the center of their thinking.

Late October 2017, and throughout the first quarter of 2018, in partnership with these new organizations, we started organizing Regeneration Midwest.17 The operating goal of this initiative is to organize a 12-state coalition to bring together a regenerative agriculture industry leadership team. This team will then set forth the direction and assemble the infrastructure to bring regenerative agriculture to scale in the Midwest.

To accomplish its purpose, Regeneration Midwest will seek to move resources and acquire market presence at a scale sufficient to unleash not only a Southeast Minnesota farmers cluster, but a multitude of clusters networked and supported across the 12 Midwest states. The blueprint for each of these clusters is the same, and the only limit is the market and the combined ability to expand, capture and sustain it.

The Regeneration Midwest platform also brings together other regenerative agriculture sectors and combines them for a higher impact across the region. Within the Regeneration Midwest organizational structure, a larger team has been engaged to organize and deploy regeneration chapters in each state. From this effort, we are now engaging farmers in Nebraska,18 Iowa, South Dakota, Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Other states are also in process of organizing and consolidating their state-based coalitions.

Our current estimates are that with at least one farmers cluster per state, and 250 meat chicken production units per cluster, we can reshape the flow of around $450 million of poultry-centered commerce. To this plan, we would aggregate the economic impact brought about through grain production and the integration of other regenerative sectors such as grass fed cattle, pork and turkey.

How You Can Participate in Building a Regenerative Agriculture System

You can help us finance the people working to organize this system by making sure you know your farmer, know your food and “vote with your fork.” Consumer choice is the foundation of the path to a better system. No matter where our compass places us, we need to start investing our daily food dollars, our retirement funds, our school, university and hospital budgets in a different system.

Every year, farmers are joining the regenerative movement because consumers choose to support them. Some start by buying from their local Community Supported Agriculture programs, farmers markets and the like. Others start urban gardens, or switch to organic foods, or become members of a food cooperative.

For farmers who want to join the system or nonprofits willing to engage in state-level organizing within the Midwest states, please reach out to the organizers of Regeneration Midwest by emailing Info@regenerationinternational.org. You can support Regeneration Midwest by making a tax-deductible donation to Regeneration International.

About the Authors: Reginaldo Haslett-Marroquin is chief strategy officer at Main Street Project and founding member of Regeneration International. Ronnie Cummins is board chair of Regeneration International and international director of the Organic Consumers Association.

This article was originally published on Mercola.com.