Peer-Reviewed Publications on Well-Managed Grazing as a Means of Improving Rangeland Ecology, Building Soil Carbon, and Mitigating Global Warming

Prepared by Soil4Climate Inc.

Updated May 2021

Left: Soil with approximately 7% soil organic matter at North Dakota farmer Gabe Brown’s holistically managed ranch. Top right: Kroon family holistically managed ranch on left side of fence, Karoo region, South Africa, with livestock density about 4X that of the neighbor’s ranch on right side of fence. Bottom right: Holistically managed herd on Maasai lands in Kenya. (Top right photo by Kroon family. Left and bottom right photos by Seth J. Itzkan.)

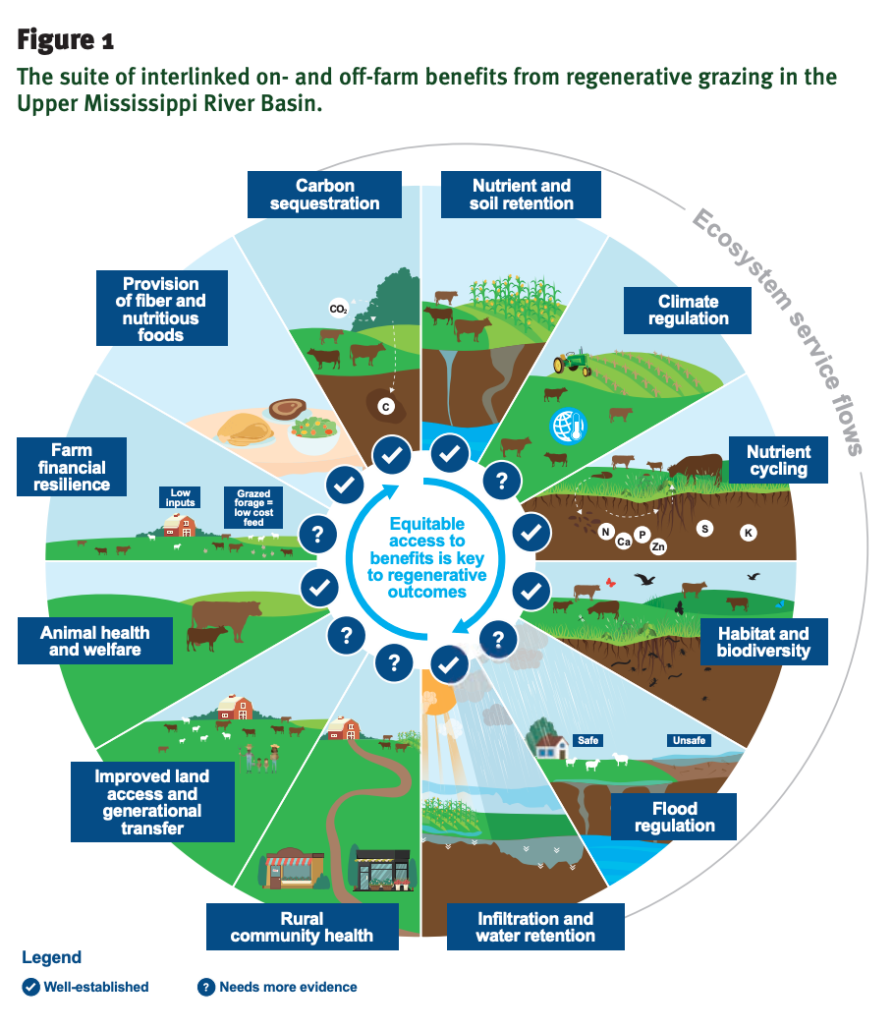

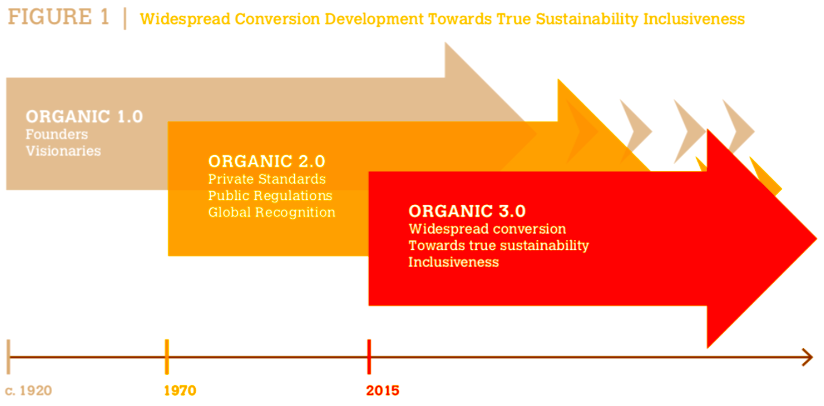

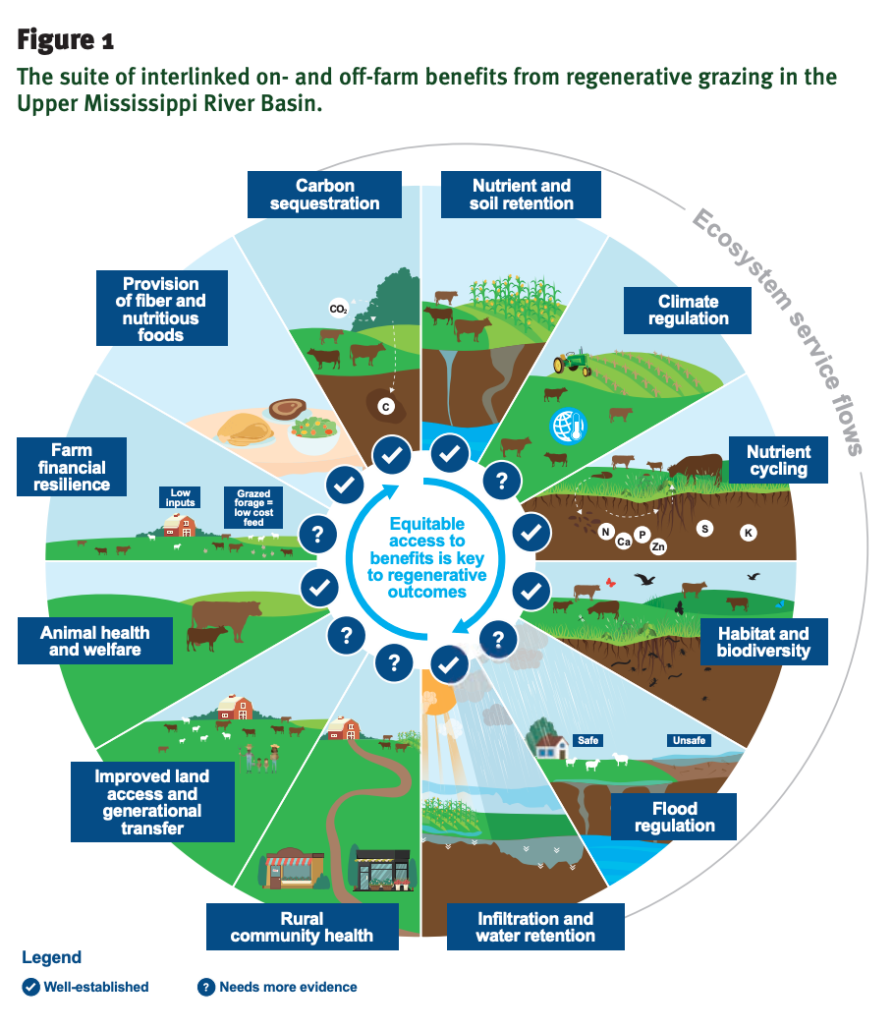

Accelerating regenerative grazing to tackle farm, environmental, and societal challenges in the upper Midwest

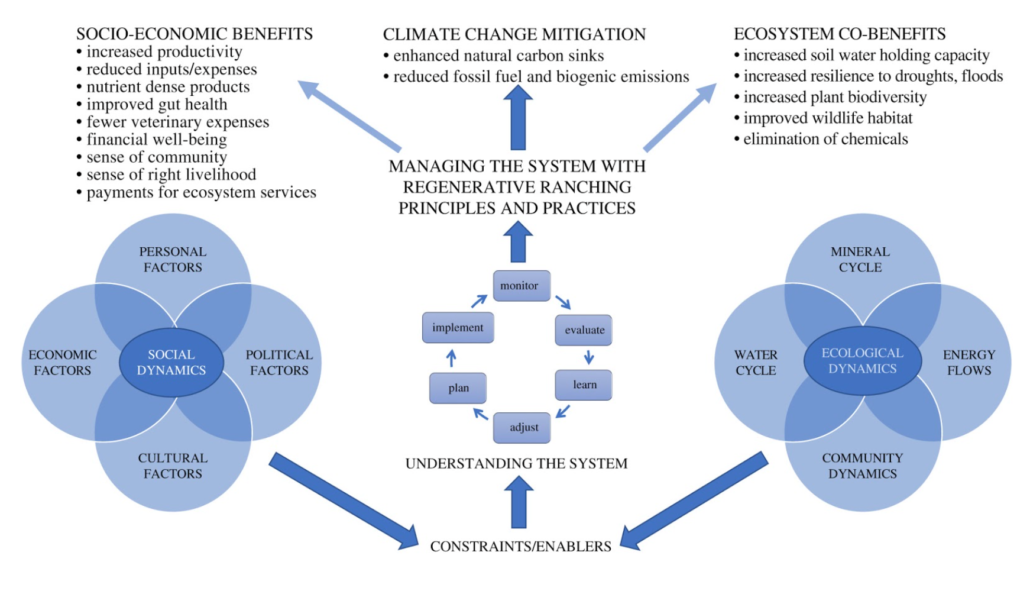

2021 Viewpoint by Spratt et al. in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation defines “regenerative grazing” as a “win-win-win” component of “regenerative agriculture” that “uses soil health and adaptive livestock management principles to improve farm profitability, human and ecosystem health, and food system resiliency.”

2021 Viewpoint by Spratt et al. in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation defines “regenerative grazing” as a “win-win-win” component of “regenerative agriculture” that “uses soil health and adaptive livestock management principles to improve farm profitability, human and ecosystem health, and food system resiliency.”

Spratt et al. 2021, doi:10.2489/jswc.2021.1209A

Expanding grass-based agriculture on marginal land in the U.S. Great Plains: The role of management intensive grazing

2021 paper by Wang et al. in Land Use Policy finds that the adoption of management intensive grazing (MIG) is a key factor for restoring marginal croplands to permanent grassland cover to enhance environmental benefits across the Great Plains from a social perspective. It also notes that compared to conventional tillage-based crop production, grass-based agriculture can provide substantially more ecosystem benefits and that management intensive grazing (MIG) offers the potential to enhance grassland resilience, thereby increasing the profitability of grass-based agriculture.

Tong Wang, Hailong Jin, Urs Kreuter, Richard Teague,Expanding grass-based agriculture on marginal land in the U.S. Great Plains: The role of management intensive grazing, Land Use Policy, Volume 104, 2021,105155,ISSN 0264-8377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105155.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837720324935

Adaptive multi-paddock grazing enhances soil carbon and nitrogen stocks and stabilization through mineral association in southeastern U.S. grazing lands

2021 paper by Mosier et al. in Journal of Environmental Management finds that adaptive multi-paddock grazing (AMP) increases both soil carbon and soil nitrogen stocks when compared with conventional grazing (CG). Specifically, carbon stocks were increased 13% and nitrogen stocks 9%. It concludes, “Findings show that AMP grazing is a management strategy to sequester C and retain N.”

Mosier S, Apfelbaum S, Byck P, Calderon F, Teague R, Thompson R, Francesca Cotrufo M, Adaptive multi-paddock grazing enhances soil carbon and nitrogen stocks and stabilization through mineral association in southeastern U.S. grazing lands, Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 288, 2021, 112409, ISSN 0301-4797, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112409

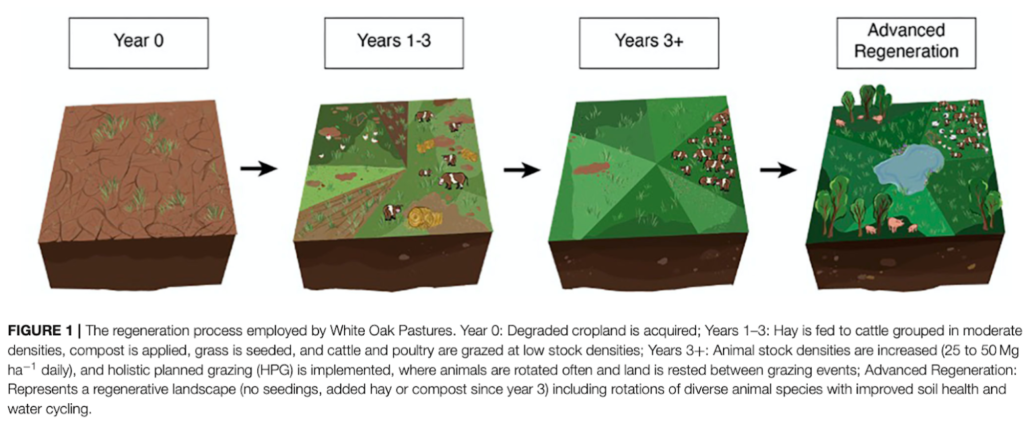

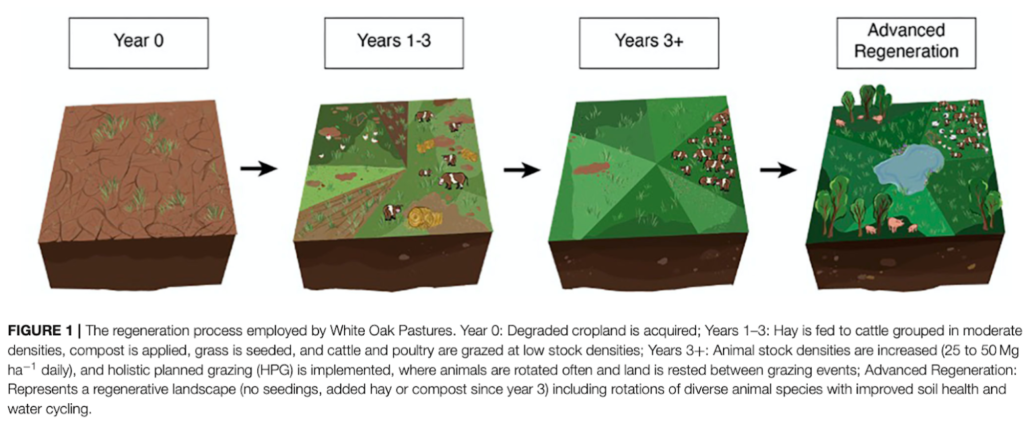

Ecosystem Impacts and Productive Capacity of a Multi-Species Pastured Livestock System

2020 paper by Rowntree et al. documents the soil carbon increases from “holistic planned grazing” in a multi-species pasture rotation (MSPR) system on the USDA-certified organic White Oak Pastures farm in Clay County, Georgia. Over 20 years, the farm sequestered an average of 2.29 metric tonnes of carbon per hectare per year (2.29 Mg C/ha/yr). The paper also shows that the area required to produce food in this regenerative way was 2.5 times that of conventional farming (which would have resulted in soil degradation and toxic chemicals impact). It notes that production efficiency comes at a cost of “land-use tradeoffs” that must be taken into consideration.

2020 paper by Rowntree et al. documents the soil carbon increases from “holistic planned grazing” in a multi-species pasture rotation (MSPR) system on the USDA-certified organic White Oak Pastures farm in Clay County, Georgia. Over 20 years, the farm sequestered an average of 2.29 metric tonnes of carbon per hectare per year (2.29 Mg C/ha/yr). The paper also shows that the area required to produce food in this regenerative way was 2.5 times that of conventional farming (which would have resulted in soil degradation and toxic chemicals impact). It notes that production efficiency comes at a cost of “land-use tradeoffs” that must be taken into consideration.

Rowntree JE, Stanley PL, Maciel ICF, Thorbecke M, Rosenzweig ST, Hancock DW, Guzman A and Raven MR (2020) Ecosystem Impacts and Productive Capacity of a Multi-Species Pastured Livestock System. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4:544984. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.544984

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.544984/full

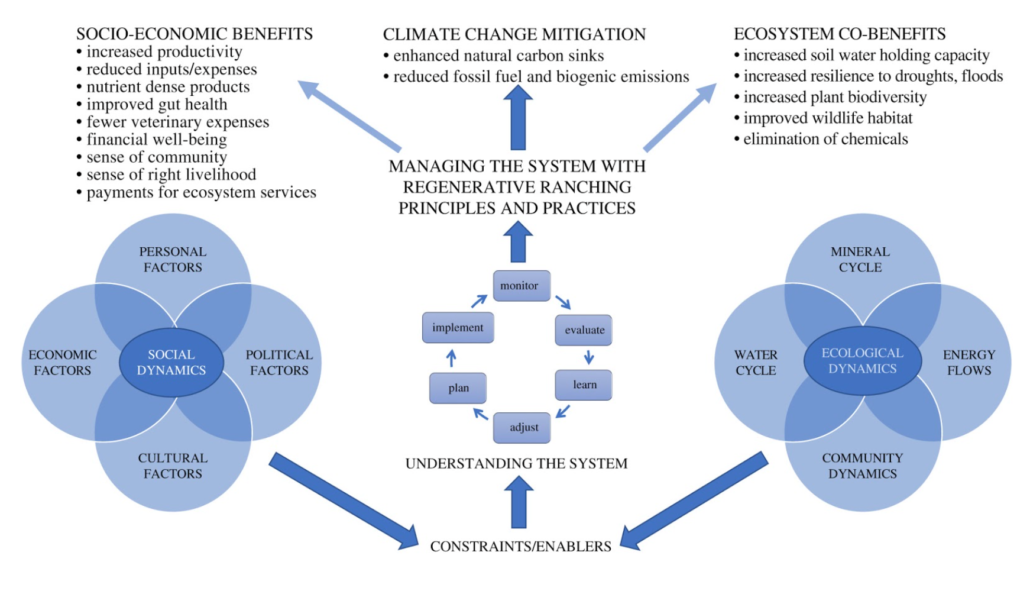

Climate change mitigation as a co-benefit of regenerative ranching: insights from Australia and the United States

2020 paper in Interface Focus finds that “‘Managed grazing’ is gaining attention for its potential to contribute to climate change mitigation by reducing bare ground and promoting perennialization, thereby enhancing soil carbon sequestration (SCS).” The paper explores principles and practices associated with the larger enterprise of ‘regenerative ranching’ (RR), which, it states, “includes managed grazing but infuses the practice with holistic decision-making.” It argues that the holistic framework is appealing “due to a suite of ecological, economic and social benefits” and notes that climate change mitigation a “co-benefit.”

2020 paper in Interface Focus finds that “‘Managed grazing’ is gaining attention for its potential to contribute to climate change mitigation by reducing bare ground and promoting perennialization, thereby enhancing soil carbon sequestration (SCS).” The paper explores principles and practices associated with the larger enterprise of ‘regenerative ranching’ (RR), which, it states, “includes managed grazing but infuses the practice with holistic decision-making.” It argues that the holistic framework is appealing “due to a suite of ecological, economic and social benefits” and notes that climate change mitigation a “co-benefit.”

Gosnell H, Charnley S, Stanley P. 2020 Climate change mitigation as a co-benefit of regenerative ranching: insights from Australia and the United States. Interface Focus 10: 20200027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2020.0027

A half century of Holistic Management: what does the evidence reveal?

2020 paper in Agriculture and Human Values provides a meta-analysis of Holistic Management (HM) considering “epistemic” differences between disciplines associated with the agricultural sciences. It concludes that the way to resolve the controversy over HM is to “research, in partnership with ranchers, rangeland social-ecological systems in more holistic, integrated ways.” This broader approach to research, it argues, can account for “the full range of human experience, co-produce new knowledge, and contribute to social-ecological transformation.”

Gosnell, Hannah & Grimm, Kerry & Goldstein, Bruce. (2020). A half century of Holistic Management: what does the evidence reveal?. Agriculture and Human Values. 10.1007/s10460-020-10016-w. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10460-020-10016-w

Soil greenhouse gas emissions as impacted by soil moisture and temperature under continuous and holistic planned grazing in native tallgrass prairie.

2020 paper in Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment finds that holistic planned grazing protocols, used in adaptive multi-paddock (AMP) management, had superior ecological performance in a tallgrass prairie region when compared with high-density continuous grazing and medium-density continuous grazing systems. Results demonstrate AMP grazing had lower soil temperature, higher soil moisture, and lower N2O and CH4 emissions.

Dowhower, S. L., Teague, W. R., Casey, K. D., & Daniel, R. (2020). Soil greenhouse gas emissions as impacted by soil moisture and temperature under continuous and holistic planned grazing in native tallgrass prairie. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 287, 106647. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106647

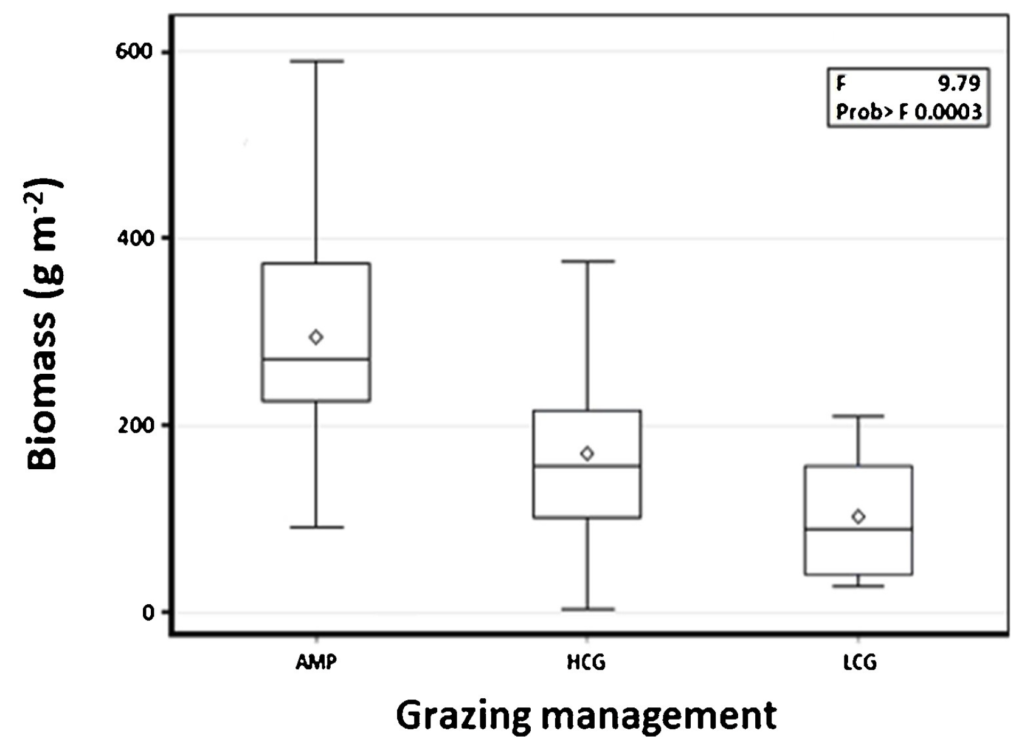

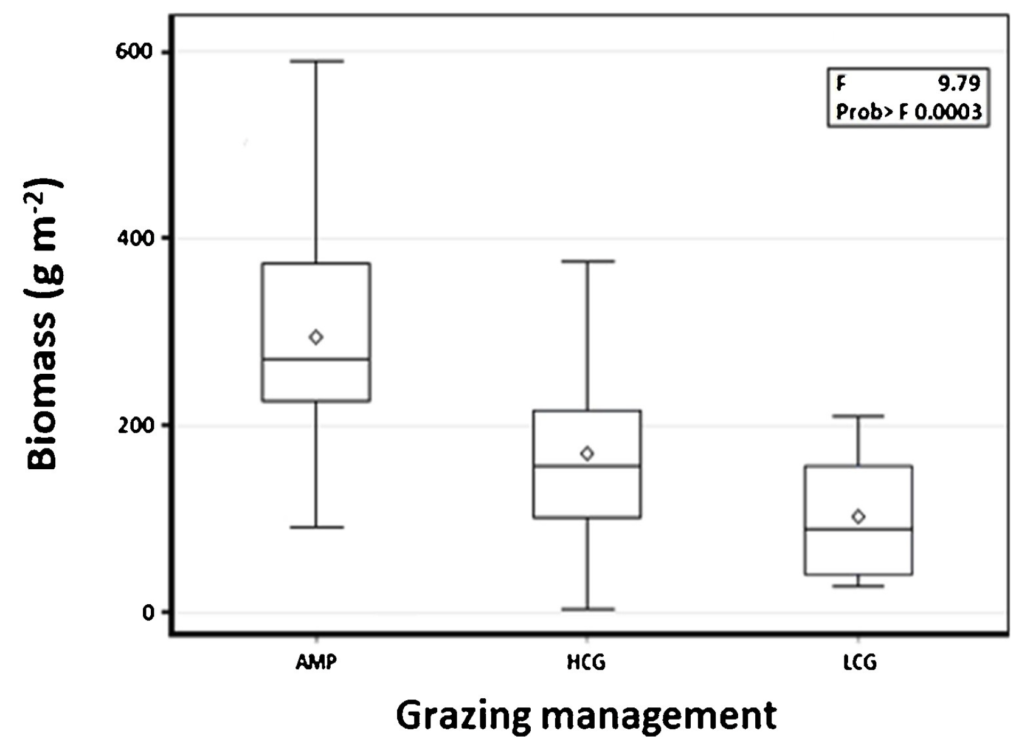

Impacts of holistic planned grazing with bison compared to continuous grazing with cattle in South Dakota shortgrass prairie

2019 paper in Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment demonstrates that Adaptive Multi-paddock (AMP) grazing increases fine litter cover, water infiltration, forage biomass and soil carbon stocks in a comparison with heavy continuous grazing (HCG) on shortgrass prairie of the Northern Great Plains of North America.

2019 paper in Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment demonstrates that Adaptive Multi-paddock (AMP) grazing increases fine litter cover, water infiltration, forage biomass and soil carbon stocks in a comparison with heavy continuous grazing (HCG) on shortgrass prairie of the Northern Great Plains of North America.

Hillenbrand, M., Thompson, R., Wang, F., Apfelbaum, S., & Teague, R. (2019). Impacts of holistic planned grazing with bison compared to continuous grazing with cattle in South Dakota shortgrass prairie. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 279, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.02.005

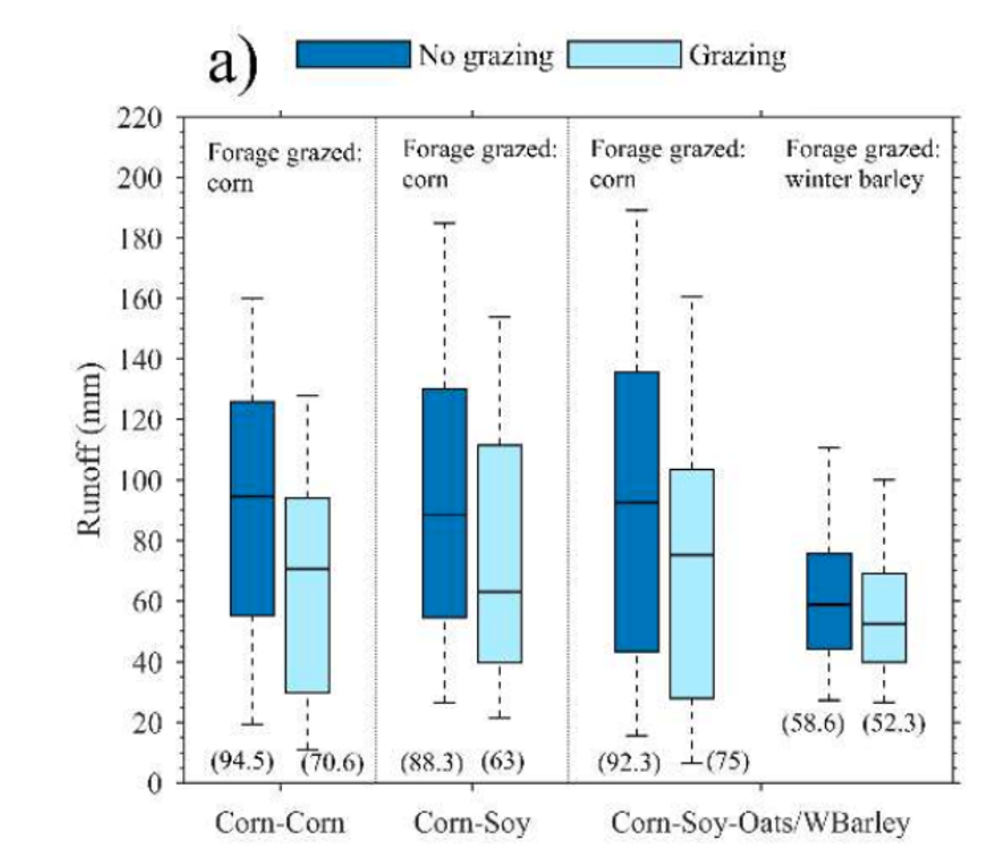

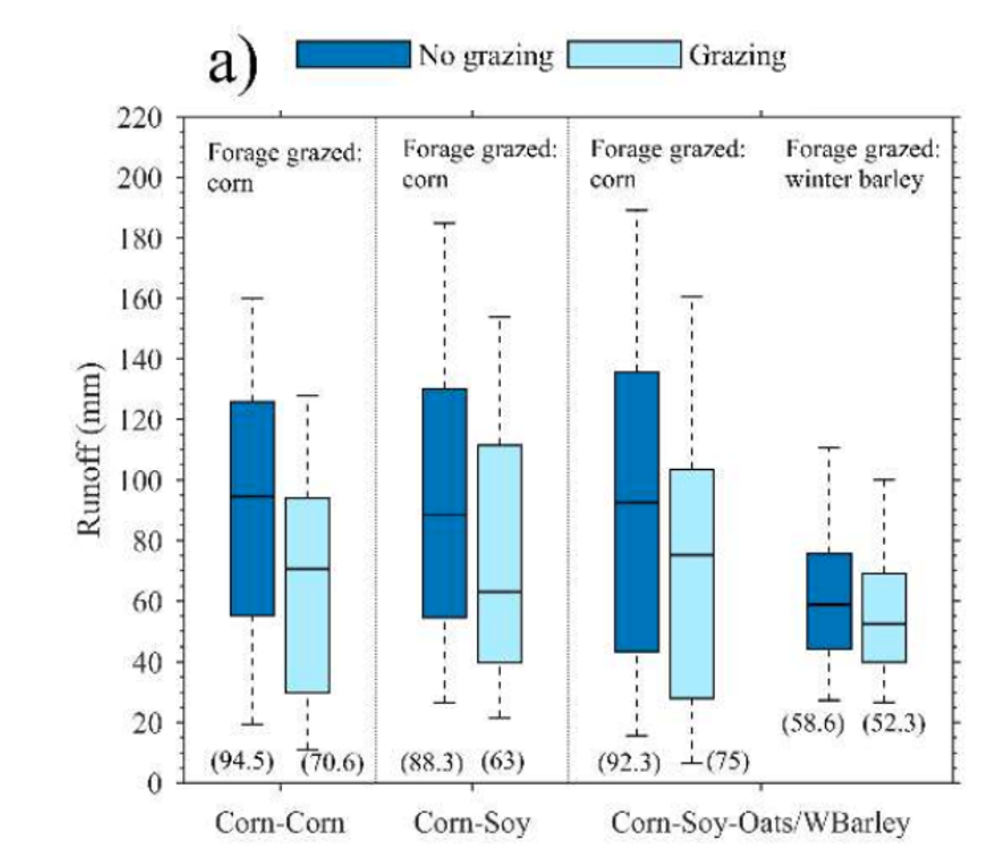

Simulating the influence of integrated crop-livestock systems on water yield at watershed scale

2019 paper in the Journal of Environmental Management shows that Integrated crop-livestock (ICL) systems have superior water retention (reduction in “water yields”) than in crops systems without a livestock grazing rotation.

2019 paper in the Journal of Environmental Management shows that Integrated crop-livestock (ICL) systems have superior water retention (reduction in “water yields”) than in crops systems without a livestock grazing rotation.

Pérez-Gutiérrez, J. D., & Kumar, S. (2019). Simulating the influence of integrated crop-livestock systems on water yield at watershed scale. Journal of Environmental Management, 239, 385–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.068

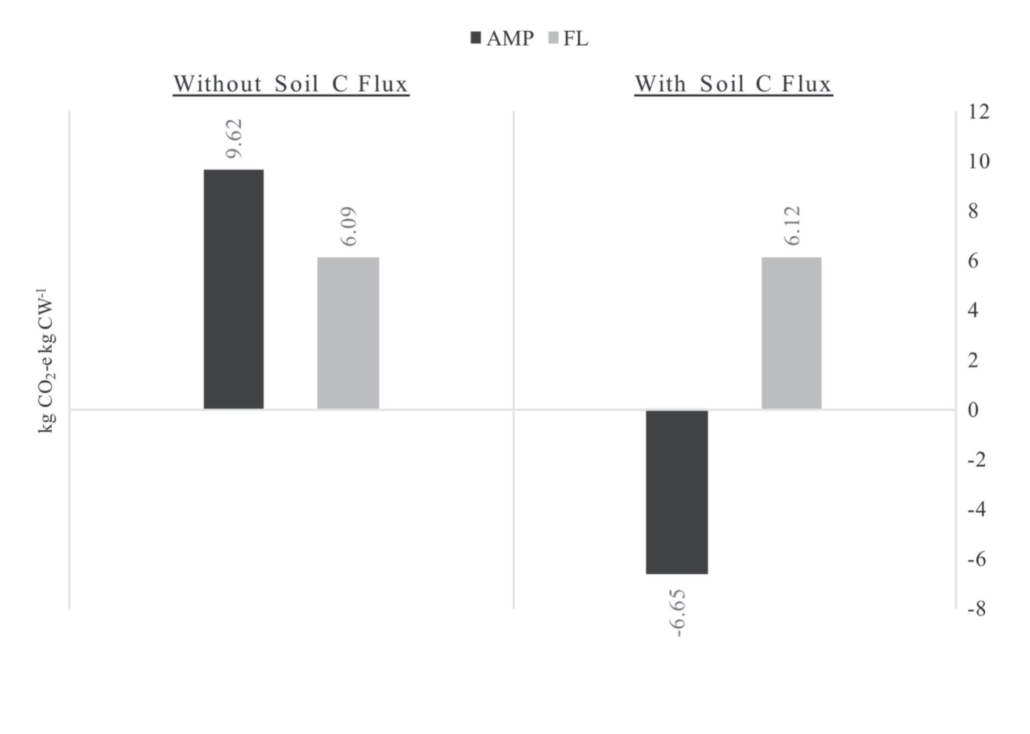

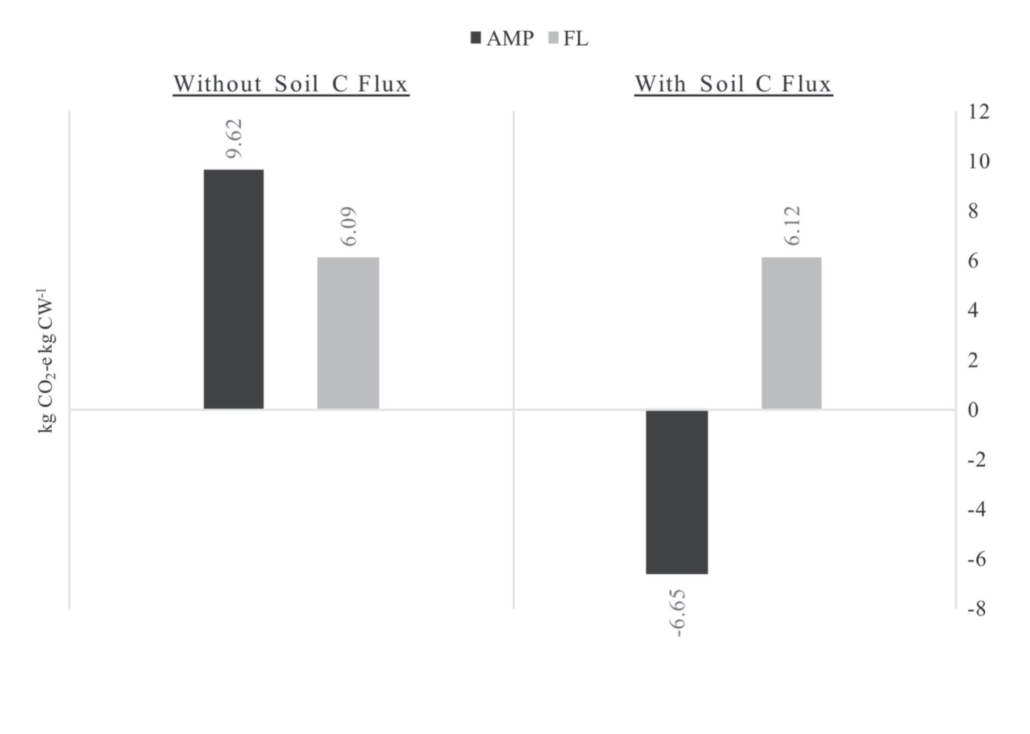

Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems

Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems

2018 Michigan State University study in Agricultural Systems finds 1.5 metric tons of carbon per acre per year drawdown via adaptive multi-paddock grazing, more than enough to offset all greenhouse gas emissions associated with the beef finishing phase.

Stanley, P. L., Rowntree, J. E., Beede, D. K., DeLonge, M. S., & Hamm, M. W. (2018). Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems. Agricultural Systems, 162, 249-258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.02.003

The effect of Holistic Planned Grazing™ on African rangelands: a case study from Zimbabwe

2018 paper in African Journal of Range & Forage Science finds positive long-term effects on ecosystem services (soils and vegetation) for Holistic Planned Grazing (HPG) and shows this approach enhancing the sustainability of livestock and wildlife.

Peel, M., & Stalmans, M. (2018). The effect of Holistic Planned Grazing™ on African rangelands: a case study from Zimbabwe. African Journal of Range & Forage Science, 35(1), 23-31. doi:10.2989/10220119.2018.1440630 https://doi.org/10.2989/10220119.2018.1440630

Enhancing soil organic carbon, particulate organic carbon and microbial biomass in semi-arid rangeland using pasture enclosures

2018 study in BMC Ecology demonstrates that controlling livestock grazing through the establishment of pasture enclosures is the key strategy for enhancing multiple ecological indicators including total soil organic carbon, and that “the establishment of enclosures is an effective restoration approach to restore degraded soils in semi-arid rangelands.” Other improved indicators include particulate organic carbon, microbial biomass carbon, and microbial biomass nitrogen.

Oduor, C.O., Karanja, N.K., Onwonga, R.N. et al. Enhancing soil organic carbon, particulate organic carbon and microbial biomass in semi-arid rangeland using pasture enclosures. BMC Ecol 18, 45 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0202-z

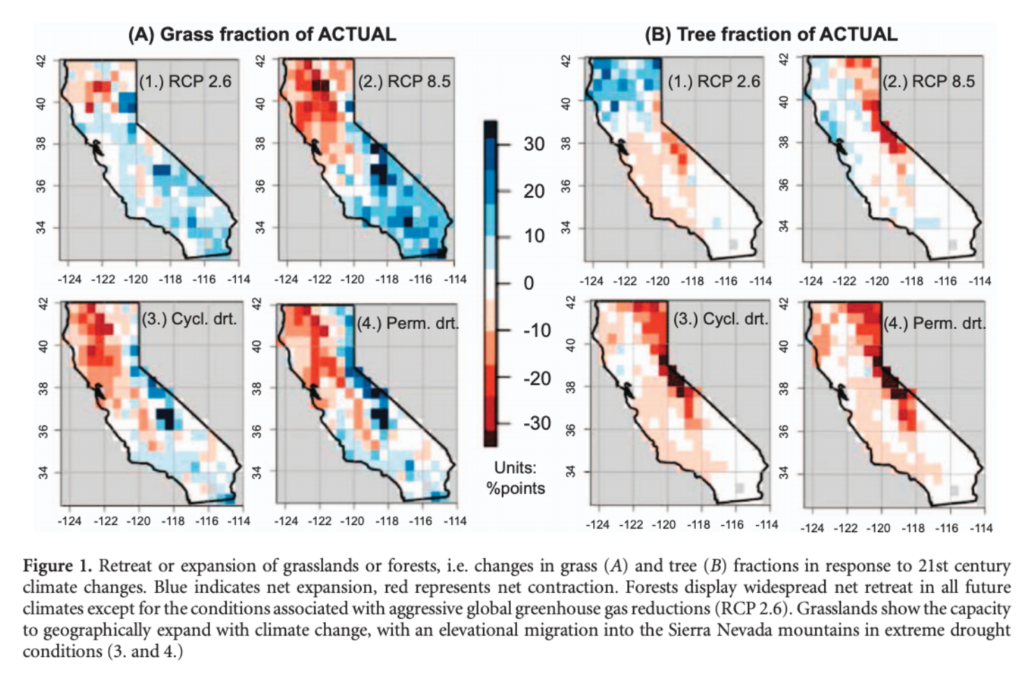

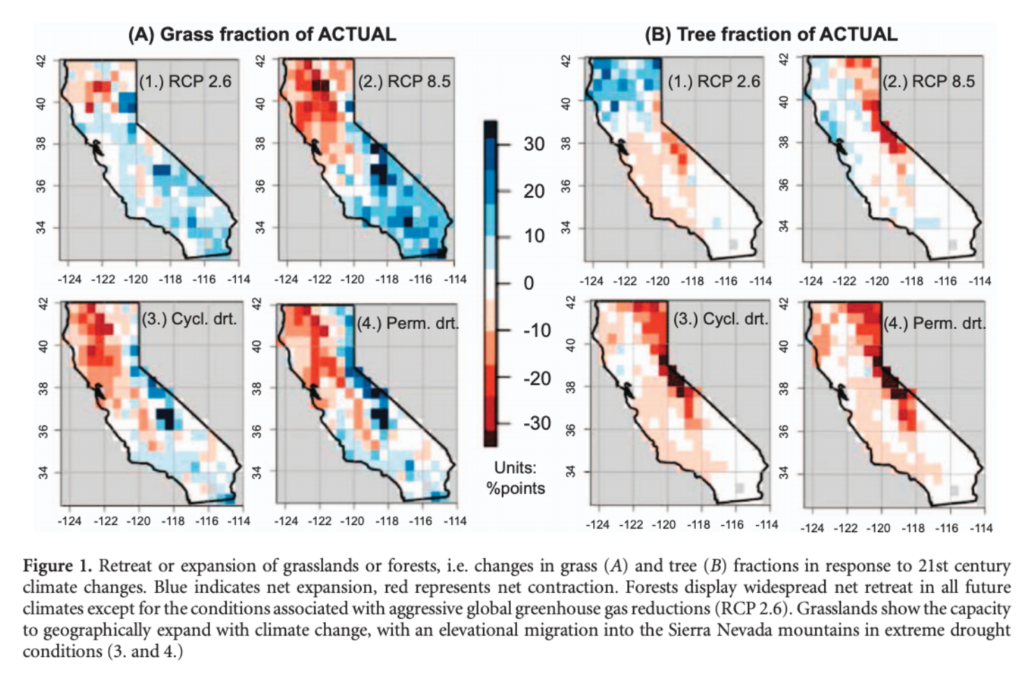

Grasslands may be more reliable carbon sinks than forests in California

2018 paper in Environmental Research Letters finds that California grasslands are a more resilient carbon sink than forests in response to 21st century changes in climate. The paper also notes that, in data compilations, herbivory has been shown to increase grassland C sequestration rates.

2018 paper in Environmental Research Letters finds that California grasslands are a more resilient carbon sink than forests in response to 21st century changes in climate. The paper also notes that, in data compilations, herbivory has been shown to increase grassland C sequestration rates.

Dass, P., Houlton, B. Z., Wang, Y., & Warlind, D. (2018). Grasslands may be more reliable carbon sinks than forests in California. Environmental Research Letters, 13(7), 074027. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aacb39

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aacb39

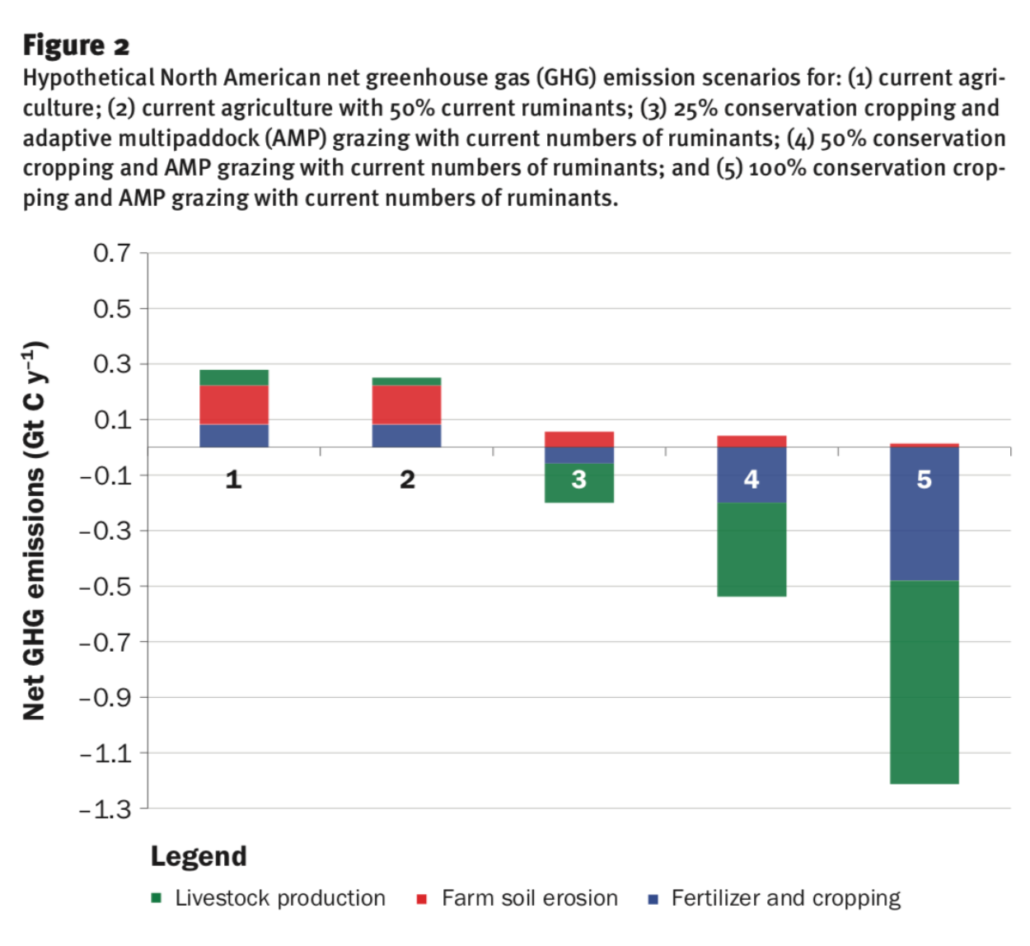

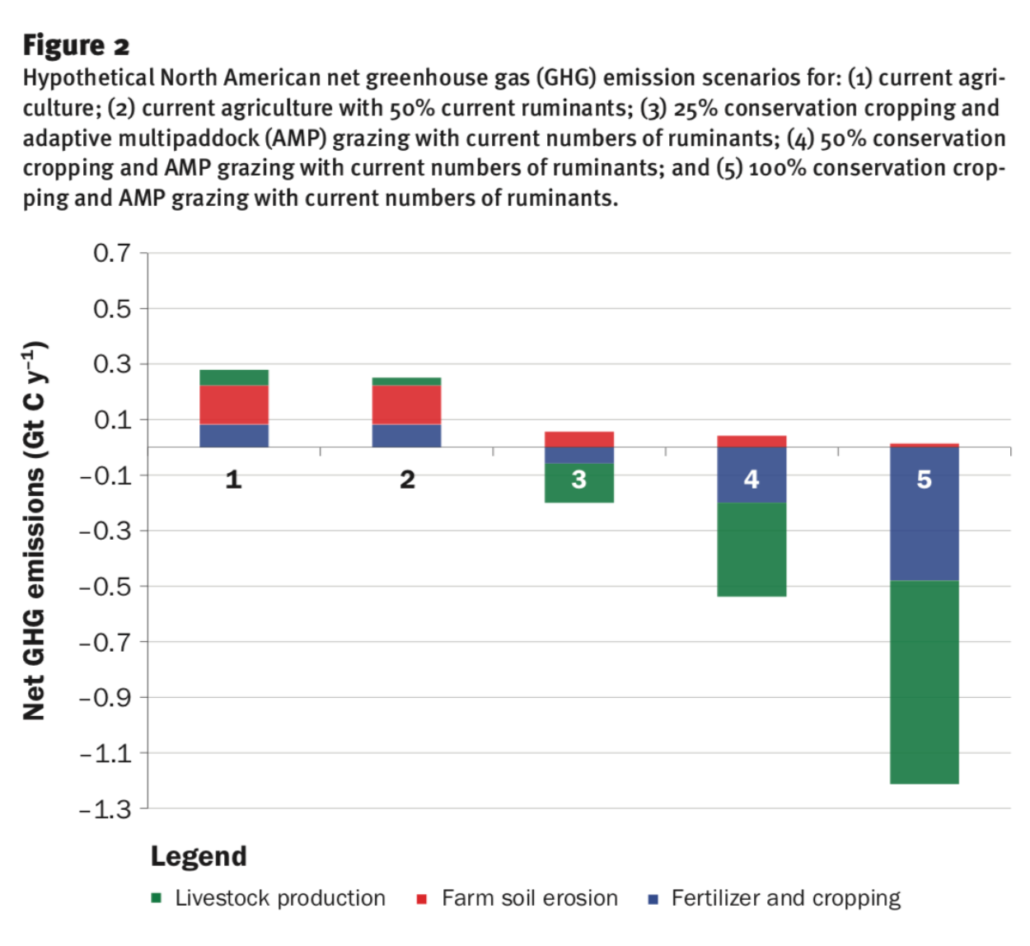

The role of ruminants in reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint in North America

2016 Texas A&M study in Journal of Soil and Water Conservation finds 1.2 metric tons of carbon per acre per year drawdown via adaptive multi-paddock grazing and the drawdown potential of North American pasturelands is 800 million metric tons of carbon per year.

2016 Texas A&M study in Journal of Soil and Water Conservation finds 1.2 metric tons of carbon per acre per year drawdown via adaptive multi-paddock grazing and the drawdown potential of North American pasturelands is 800 million metric tons of carbon per year.

Teague, W. R., Apfelbaum, S., Lal, R., Kreuter, U. P., Rowntree, J., Davies, C. A., R. Conser, M. Rasmussen, J. Hatfield, T. Wang, F. Wang, Byck, P. (2016). The role of ruminants in reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint in North America. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 71(2), 156-164. doi:10.2489/jswc.71.2.156 http://www.jswconline.org/content/71/2/156.full.pdf+html

Potential mitigation of midwest grass-finished beef production emissions with soil carbon sequestration in the United States of America

2016 paper in Journal on Food, Agriculture & Society finds that where soil carbon sequestration is included in a life cycle assessment of Midwest grass-finished beef production systems, such systems can be overall carbon sinks.

Rowntree, J., Ryals, R., Delonge, M., Teague, R. W., Chiavegato, M., Byck, P., . . . Xu, S. (2016). Potential mitigation of midwest grass-finished beef production emissions with soil carbon sequestration in the United States of America. Future of Food: Journal on Food, Agriculture & Society, 4(3), 8. https://asu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/potential-mitigation-of-midwest-grass-finished-beef-production-em.

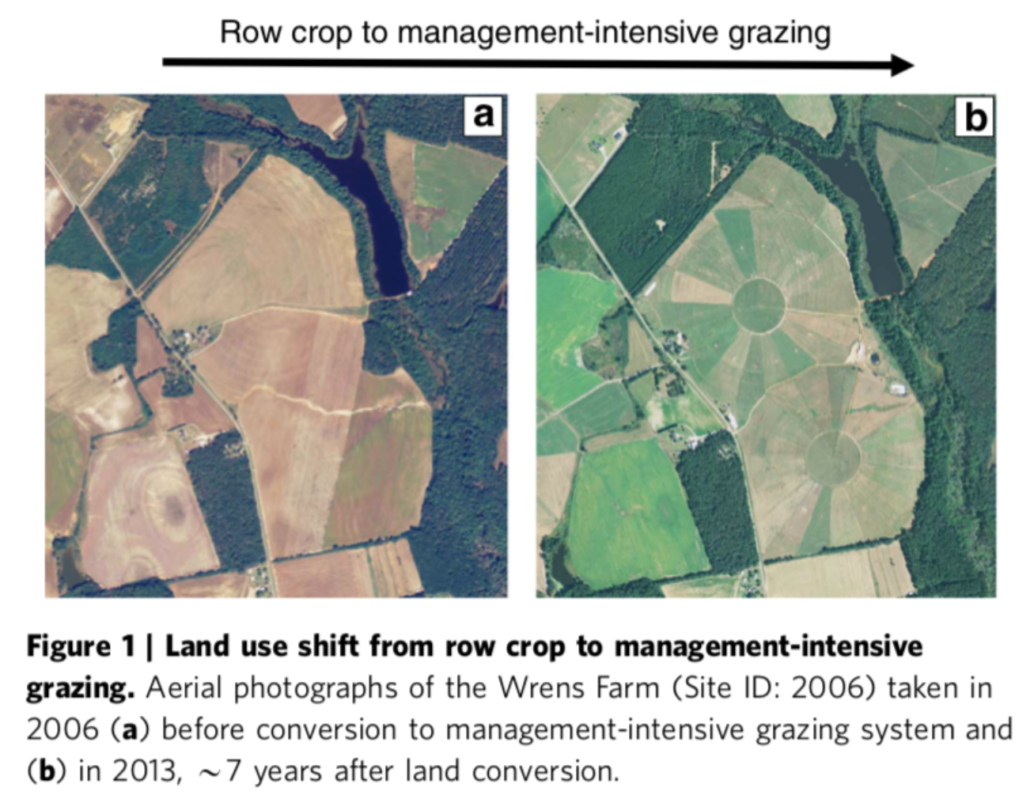

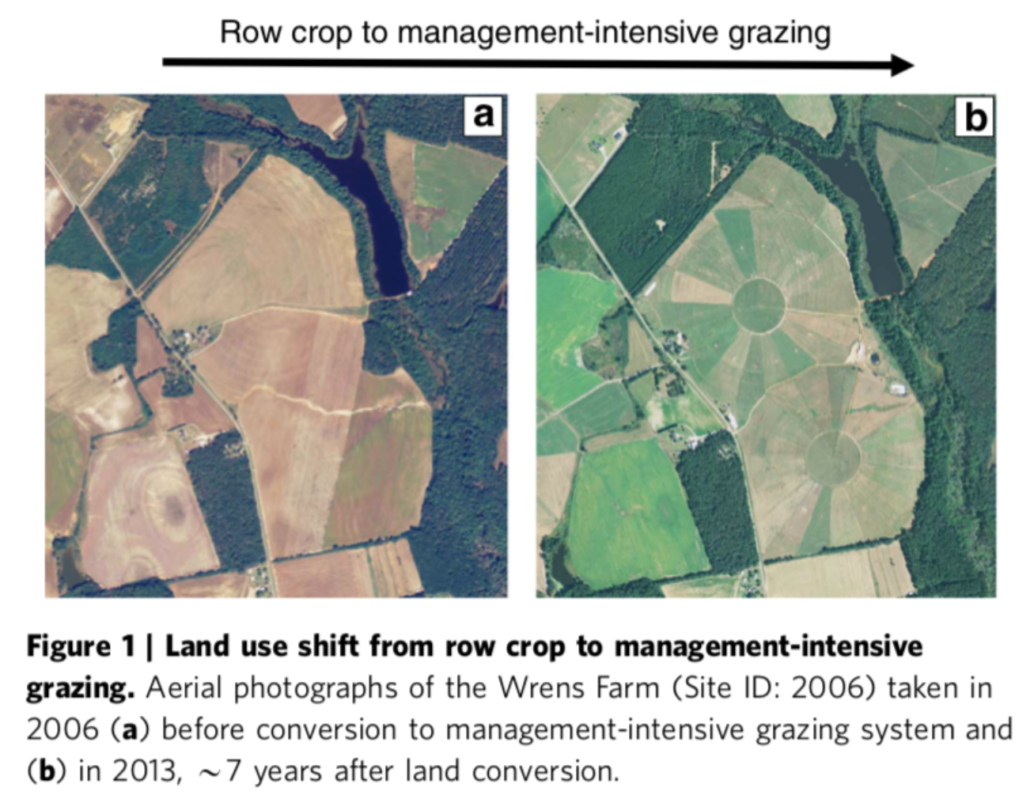

Emerging land use practices rapidly increase soil organic matter

2015 University of Georgia study in Nature Communications finds 3 metric tons of carbon per acre per year drawdown following a conversion from row cropping to regenerative grazing.

2015 University of Georgia study in Nature Communications finds 3 metric tons of carbon per acre per year drawdown following a conversion from row cropping to regenerative grazing.

Machmuller, M. B., Kramer, M. G., Cyle, T. K., Hill, N., Hancock, D., & Thompson, A. (2015). Emerging land use practices rapidly increase soil organic matter. Nature Communications, 6, 6995. doi:10.1038/ncomms7995 https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms7995

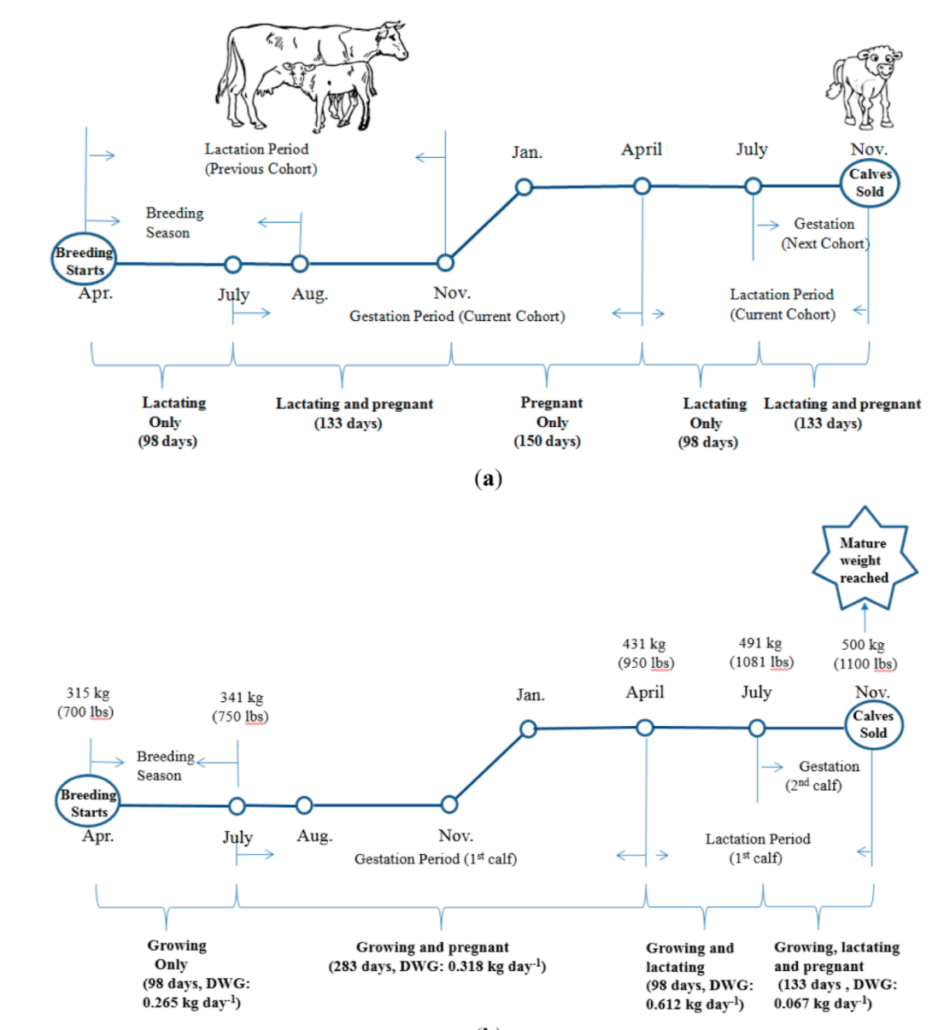

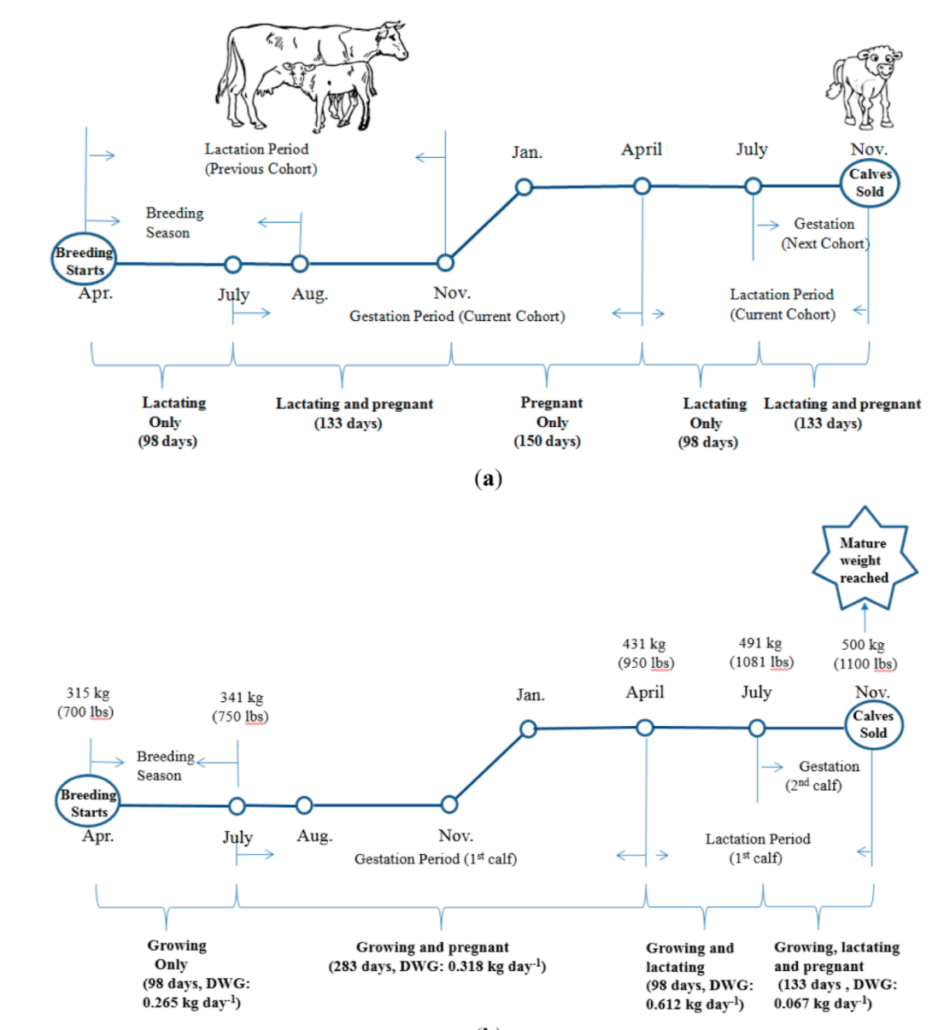

GHG Mitigation Potential of Different Grazing Strategies in the United States Southern Great Plain

2015 paper in Sustainability finds that a conversion from heavy continuous to multi-paddock grazing on cow-calf farms in the US southern Great Plains can result in a carbon sequestration rate in soil of 2 tonnes per hectare per year or approximately 0.89 tonnes per acre per year. In a sensitivity analysis that accounts for farm animal emissions, this sequestration in soil is sufficient to make the farm a net carbon sink for decades.

2015 paper in Sustainability finds that a conversion from heavy continuous to multi-paddock grazing on cow-calf farms in the US southern Great Plains can result in a carbon sequestration rate in soil of 2 tonnes per hectare per year or approximately 0.89 tonnes per acre per year. In a sensitivity analysis that accounts for farm animal emissions, this sequestration in soil is sufficient to make the farm a net carbon sink for decades.

Wang, T., Teague, W., Park, S., & Bevers, S. (2015). GHG Mitigation Potential of Different Grazing Strategies in the United States Southern Great Plains. Sustainability, 7(10), 13500. Retrieved from http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/7/10/13500

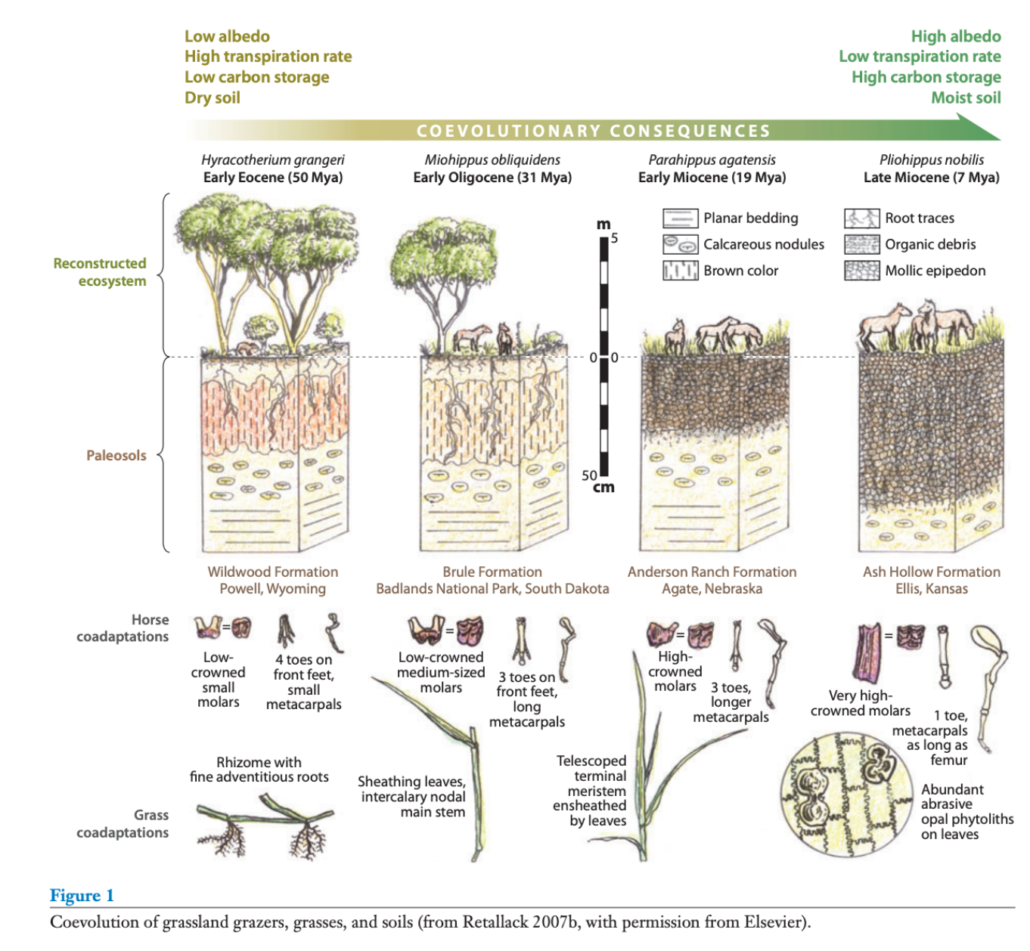

Global Cooling by Grassland Soils of the Geological Past and Near Future

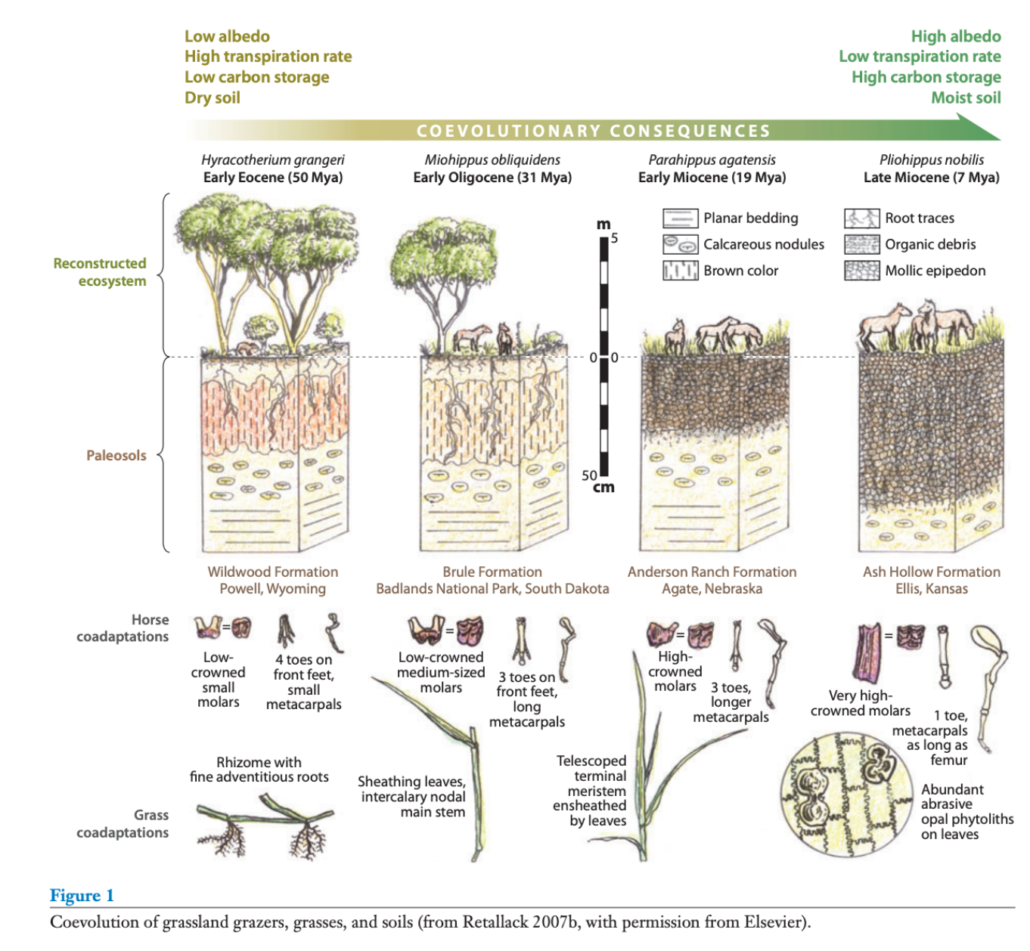

2013 paper in Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences by University of Oregon Department of Geological Sciences professor Gregory J. Retallack shows the co-evolution of ruminants and grassland soils (mollisols) was essential for geologic cooling of the past 20 million years – leading to the conditions suitable for human evolution – and can be an instrumental part of the necessary cooling in the future to reverse global warming.

2013 paper in Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences by University of Oregon Department of Geological Sciences professor Gregory J. Retallack shows the co-evolution of ruminants and grassland soils (mollisols) was essential for geologic cooling of the past 20 million years – leading to the conditions suitable for human evolution – and can be an instrumental part of the necessary cooling in the future to reverse global warming.

Retallack, G. (2013). Global Cooling by Grassland Soils of the Geological Past and Near Future (Vol. 41, pp. 69–86): Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-050212-124001

Sustainability of holistic and conventional cattle ranching in the seasonally dry tropics of Chiapas, Mexico

2013 study in Agricultural Systems finds practitioners of Holistic Management in the dry tropics region of Chiapas, Mexico have denser grass, deeper topsoil, and more earthworms in their pastures than conventional graziers, and that “Holistic management is leading to greater ecological and economic sustainability.”

Ferguson, B. G., Diemont, S. A. W., Alfaro-Arguello, R., Martin, J. F., Nahed-Toral, J., Álvarez-Solís, D., & Pinto-Ruíz, R. (2013). Sustainability of holistic and conventional cattle ranching in the seasonally dry tropics of Chiapas, Mexico. Agricultural Systems, 120, 38-48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2013.05.005

Tall Fescue Management in the Piedmont: Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen

2012 study in Soil Science Society of America Journal demonstrates improved grazing management systems can have an enormous benefit on surface soil fertility restoration of degraded soils in the southeastern United States, and managed grazing can sequester 1.5 metric tons of carbon per hectare per year.

Franzluebbers, A. J., D. M. Endale, J. S. Buyer, and J. A. Stuedemann. 2012. Tall Fescue Management in the Piedmont: Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 76:1016-1026. doi:10.2136/sssaj2011.0347

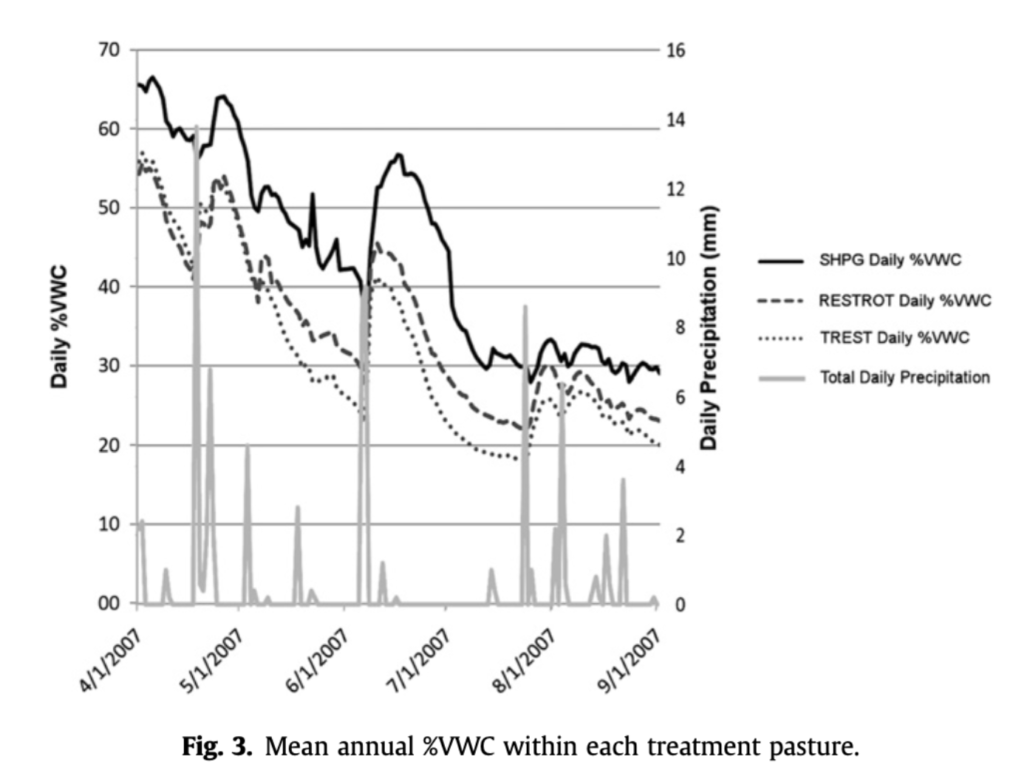

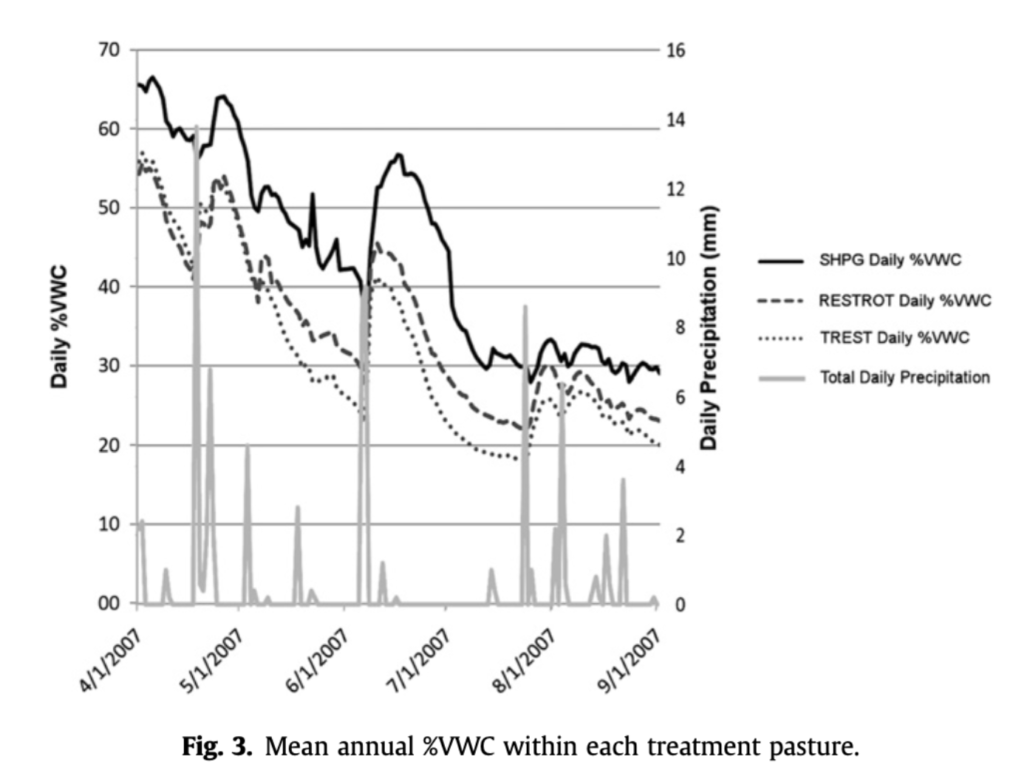

Effect of grazing on soil-water content in semiarid rangelands of southeast Idaho

2011 paper in Journal of Arid Environments finds simulated holistic planned grazing (SHPG) had significantly higher percent volumetric-water content (%VWC) after two years of comparison with similar ranch plots using rest-rotation (RESTROT), and total rest (TREST) systems in semiarid rangelands of southeast Idaho. Measured percent volumetric-water content were 45.8 for SHPG and 34.7 and 29.8 for RESTROT and TREST, respectively.

2011 paper in Journal of Arid Environments finds simulated holistic planned grazing (SHPG) had significantly higher percent volumetric-water content (%VWC) after two years of comparison with similar ranch plots using rest-rotation (RESTROT), and total rest (TREST) systems in semiarid rangelands of southeast Idaho. Measured percent volumetric-water content were 45.8 for SHPG and 34.7 and 29.8 for RESTROT and TREST, respectively.

Weber, K. T., & Gokhale, B. S. (2011). Effect of grazing on soil-water content in semiarid rangelands of southeast Idaho. Journal of Arid Environments, 75(5), 464-470. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.12.009

Grazing management impacts on vegetation, soil biota and soil chemical, physical and hydrological properties in tall grass prairie

2011 paper in Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment demonstrates multi-paddock grazing of the type recommended by Allan Savory, and representative of Holistic Management, led to improved soil health indicators including higher bulk density, greater infiltration rate, and increased fungal/bacterial ratios when compared with continuous single-paddock grazing, typical of conventional practice. Soil organic matter averaged 3.61% in the multi-paddock ranches, compared to 2.4% for heavy continuous, single-paddock grazing.

Teague, W. R., Dowhower, S. L., Baker, S. A., Haile, N., DeLaune, P. B., & Conover, D. M. (2011). Grazing management impacts on vegetation, soil biota and soil chemical, physical and hydrological properties in tall grass prairie. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 141(3–4), 310-322. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2011.03.009

Benefits of multi-paddock grazing management on rangelands: Limitations of experimental grazing research and knowledge gaps

2008 chapter in “Grasslands: Ecology, Management, and Restoration,” published by H. G. Schroder, finds in a comprehensive literature review that multi-paddock rotational grazing produces superior results for grassland ecology when compared to conventional continuous grazing. It also finds that misunderstandings exist in the management techniques needed to achieve these benefits and in the scientific protocols required to assess them.

Teague, W. R., Provenza, F., Norton, B., Steffens, T., Barnes, M., Kothmann, M. M., & Roath, R. (2008). Benefits of multi-paddock grazing management on rangelands: Limitations of experimental grazing research and knowledge gaps. In H. G. Schroder (Ed.), Grasslands: Ecology, Management, and Restoration (pp. 41-80): Nova Science Publishers, NY. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285918973_Benefits_of_multi-paddock_grazing_management_on_rangelands_Limitations_of_experimental_grazing_research_and_knowledge_gaps

2021 Viewpoint by Spratt et al. in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation defines “regenerative grazing” as a “win-win-win” component of “regenerative agriculture” that “uses soil health and adaptive livestock management principles to improve farm profitability, human and ecosystem health, and food system resiliency.”

2021 Viewpoint by Spratt et al. in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation defines “regenerative grazing” as a “win-win-win” component of “regenerative agriculture” that “uses soil health and adaptive livestock management principles to improve farm profitability, human and ecosystem health, and food system resiliency.” 2020 paper by Rowntree et al. documents the soil carbon increases from “holistic planned grazing” in a multi-species pasture rotation (MSPR) system on the USDA-certified organic White Oak Pastures farm in Clay County, Georgia. Over 20 years, the farm sequestered an average of 2.29 metric tonnes of carbon per hectare per year (2.29 Mg C/ha/yr). The paper also shows that the area required to produce food in this regenerative way was 2.5 times that of conventional farming (which would have resulted in soil degradation and toxic chemicals impact). It notes that production efficiency comes at a cost of “land-use tradeoffs” that must be taken into consideration.

2020 paper by Rowntree et al. documents the soil carbon increases from “holistic planned grazing” in a multi-species pasture rotation (MSPR) system on the USDA-certified organic White Oak Pastures farm in Clay County, Georgia. Over 20 years, the farm sequestered an average of 2.29 metric tonnes of carbon per hectare per year (2.29 Mg C/ha/yr). The paper also shows that the area required to produce food in this regenerative way was 2.5 times that of conventional farming (which would have resulted in soil degradation and toxic chemicals impact). It notes that production efficiency comes at a cost of “land-use tradeoffs” that must be taken into consideration. 2020 paper in

2020 paper in 2019 paper in

2019 paper in  2019 paper in the

2019 paper in the Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems

Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems 2018 paper in

2018 paper in  2016 Texas A&M study in

2016 Texas A&M study in 2015 University of Georgia study in

2015 University of Georgia study in 2015 paper in

2015 paper in  2013 paper in

2013 paper in  2011 paper in

2011 paper in