[ English | Français ]

Author: Oliver Gardiner

Sowing Seeds of Knowledge on Dry Land

Sowing Seeds of Knowledge on Dry Land

A catalyst to share knowledge on soil climate resiliency between North African Nations and to bring global awareness and advocacy on the dangers proliferated by climate change and desertification in arid environments.

The “CARI Association” (Centre d’Action et de Realisation Internationales) is an NGO based near Montpellier, France, that supports small scale farmers through its local partners based in North African and Sub-Saharan countries.

Founded in 1998 by its current Director Patrice Burger, CARI was one of the first European NGOs to work closely with the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

Based on an informal European networking initiative on desertification (eniD), CARI and partners from 15 countries responded to a call from the European Union in 2007 and launched “Drynet” a major global initiative to tackle desertification. The initiative now operates on every continent from Asia to Latin America.

Desertification occurs in arid, semi arid and sub humid environments where lands are degraded by human activity and climate change.According to the UNCCD, 110 countries are hit by desertification and each year 12 million hectares of farmland disappear worldwide, causing the equivalent loss of 20 million tons of cereals.

Actions to fight desertification and preserve ecosystems in arid environments

The CARI Association is based in the Languedoc Region of Southern France, where young land practitioners who understand the triple bottom line effects of soil regeneration flourish and proliferate within the region’s prosperous countryside.

It is here, by word of mouth alone, that CARI recruits its field educators to support local farming communities in the dry regions of North West Africa to adopt regenerative farming practices in the face of arid conditions and degrading lands.

CARI operates on the ground with a dual approach:

- Sharing practical knowledge and scientific advice on water cycling management, cover crop increase, advanced composting techniques, biomass and livestock management.

- Assisting local representatives showcase the solutions they have put into practice to develop impoverished and desertified areas by bringing organic farming and the conservation of natural ecosystems to the heart of national public debates and international body conventions such as the UNCCD.

Pilot farm in Jorf, Morocco

Pilot farm in Jorf, Morocco

Since 2013 CARI has helped to expand and develop a family oasis farm in Morocco that is now increasingly climate resilient and serves as a demonstration base for farmers from across Morocco who want to optimize their land and farming skills.

The Jorf Farm has forged a solid reputation both nationally and internationally and has so far helped over 400 Moroccan farmers deepen their knowledge and practice of regenerative agriculture.

An Oasis Farm is where privately owned oasis land generates economic activities. Oases are ecosystems that have been established and maintained by land stewards over millennia through the rigorous management of natural resources, within environments that are exposed to extremely arid conditions.

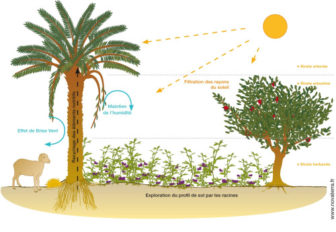

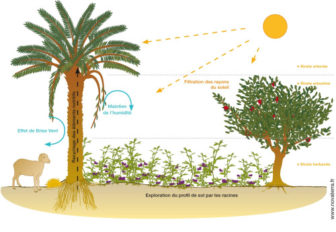

The oases of the Maghreb desert regions (Northern Sahara) are subject to a phenomena called the “Oasis Effect”. It is a three layered growing system characterised by towering date palms that provide enough shade to establish microclimates for smaller trees and crops to survive. These systems produce a surprisingly large variety of fruits, vegetables, cereals and medicinal and aromatic plants, while also leaving space for fodder plants which can feed livestock (goats, sheep, camels) that in turn fertilize the soil with their manure.

The oases of the Maghreb desert regions (Northern Sahara) are subject to a phenomena called the “Oasis Effect”. It is a three layered growing system characterised by towering date palms that provide enough shade to establish microclimates for smaller trees and crops to survive. These systems produce a surprisingly large variety of fruits, vegetables, cereals and medicinal and aromatic plants, while also leaving space for fodder plants which can feed livestock (goats, sheep, camels) that in turn fertilize the soil with their manure.

Today, oases are challenged by climate change which could lead to their desertification. The maintenance of the services provided by oases (desert resiliency, refuge for biodiversity, climate regulation, and food security) and the development of climate adaptation practices are of huge importance.

Oases conservation and agro-ecological developments

Oases conservation and agro-ecological developments

CARI coordinates a broader initiative called RADDO, a network of organizations for the sustainable development of Oases, that carries out a variety of conservation operations and agro-ecological training programs through the network of oases in Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Niger and Chad.

This important program contributes to seed biodiversity by helping oasis farmers select and reproduce local varieties and establish seed exchange banks.

Agro-ecological training center in Beni-Isgen, Algeria

For the past three years, through a joint initiative, RADDO and APEB (The Association for Environmental Protection of Beni-Isgen) have been expanding the Akraz agro-ecology training center in Beni-Isgen, Algeria.

The center provides a residency, classrooms, research facilities and an experimental farm for agro-ecological practices. This is where three levels of apprenticeship in agro-ecology are taught; trainer certification programs, improvement courses for farmers and career studies for young students.

Teachers at the Akraz center are certified agronomists with extensive experience in agriculture and farming and receive additional training to ensure they are fully competent to transfer on knowledge of the principles of agro-ecology.

The center also organizes networking initiatives for farmers to exchange knowledge and their vision of what is needed to develop public community engagement in overcoming issues such as soil degradation, water shortages and the loss of biodiversity.

Projects like Akraz represent a new paradigm of development for the future of oases and their populations, with continuous professional training programs and actions to sensitize environmental oases resiliency.

CARI Director, Patrice Burger explains that their efforts on the ground may be successful but that they need to scale up in order to protect more people that are extremely vulnerable to climate change and to desertification.

This is one of the reasons why the CARI Association works tirelessly to advocate the challenges of dry-land and arid environments.

In June 2015 CARI initiated “Deserti’factions” an International Civil Society Forum dedicated to land degradation and combating desertification. The event brought together 300 stakeholders from over 56 countries.

The forum was followed by one day event in the French City Center of Montpellier to raise public awareness and prepare inputs for the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) of the United Nations Framework on Climate Change in Paris.

On December 1st 2015, CARI became a member of the 4p1000 Initiative, an international agreement launched by the French government and signed by 26 countries to demonstrate that agricultural soils can play a crucial role in food security and climate mitigation through atmospheric carbon drawdown.

Climate change is affecting millions of people in arid zones. With the current migration crises faced in Europe, it has become crucial for organizations such as CARI to increase and expand their activities in order to help prevent future population displacements and conflicts over food and water scarcity. To support and learn more about CARI please visit www.CariAssociation.org

***

Oliver Gardiner is a freelance journalist based in London, UK. Oliver provides media content for NGOs and has long served as a freelance radio reporter on shows like “The Current” on CBC Radio One, having worked several years as legal interpreter with the UK Immigration Authorities, Oliver has an in-depth understanding of the links between desertification and mass migration. His coverage on topics such as 4p1000 during COP21 and his personal commitment in developing media strategies to showcase regenerative agriculture as key to reversing climate change has led him to develop further stories with Regeneration International.